DSC Multilingual Mystery #1: Lee and the Missing Metadata#

by Lee Skallerup Bessette and Quinn Dombrowski

January 24, 2020

https://doi.org/10.25740/gd239vj6434

https://doi.org/10.25740/gd239vj6434

Quinn#

I engaged in some retail therapy over the holidays. With a little Christmas money burning a hole in my pocket, and two weeks on the East Coast visiting relatives with three small kids in tow, sitting down with a beer at the end of the day and hunting down translations of Baby-Sitters Club books was a reliable small source of joy.

The Data-Sitters Club has become something of an awkward undertaking for me, in relation to my job. I support non-English DH at Stanford, and help run a Multilingual DH group. While we’d managed to acquire the complete corpus of The Baby-Sitters Club with financial support from the Stanford Literary Lab, we were nearly out of money and all we had was English. I had a good story to explain why I was doing it: the methods we’re walking through in these posts can, in most cases, be applied to non-English text as well, given some care and pre-processing. But still, it bugged me. Non-English DH is where I feel most at home, and since the series has been translated – at least in part – into over 15 languages, aren’t there things we should explore with those versions, too?

(If you’re wondering what the deal is with the Data-Sitters Club, read Chapter 2.)

As MSNBC talking heads, 15-year-old reruns of Law & Order, or, on a good night, Discovery Channel docu-dramas of harsh, unforgiving nature flashed across the TV at my in-laws’ house, and my jet-lagged children attempted to postpone sleep indefinitely by jumping on an air mattress upstairs, I curled up on the couch with my laptop and lost myself in WorldCat.

Amazon or AbeBooks is fine if you know what you’re looking for. Katia managed to get us a number of recent French translations that way using the Literary Lab funds. Some of them even arrived at my in-laws’ over the holidays, leaving me giggling at the temptation for mistranslation based on near-cognates. Claudia’s Ennui. Lucy Is Amorous.

But truly, I had nearly no idea what I was looking for. The “Translations” page on a BSC fan wiki had a list of languages, without claiming it was comprehensive. Under the French translation, someone had put together a list of book titles that had been published in Quebec. There was also a list of titles for Finnish and for Polish. (For the latter, titles had been announced for five translations, but only three were ever published.) I knew there had to be more out there. So I pulled out a search technique I’d tried before and often recommended to people who were looking for translations, without knowing many more details: I went to WorldCat.

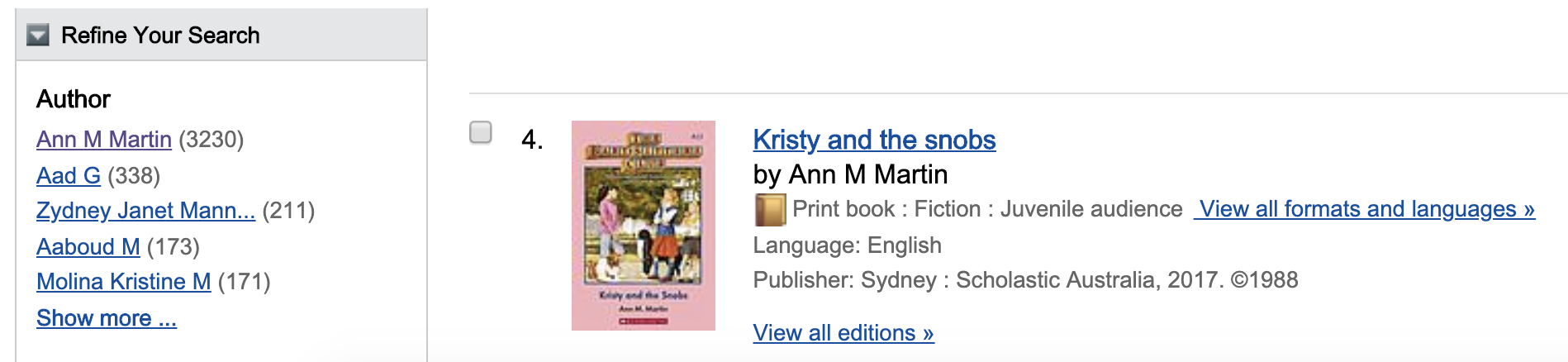

If you haven’t really used it, WorldCat aggregates metadata records from libraries around the world. It’s like a meta-library-catalog, with the usual features you’d expect from a library catalog (e.g. searching by particular fields – like author or title, and lots of different ways to refine your search using facets). There’s a really interesting mix of libraries represented, from public school libraries in the US to national libraries in Europe to teachers’ colleges in Asia. I’m sure many, many libraries and archives, particularly in the Global South, are not there (thinking about this from the perspective of Roopsi’s book New Digital Worlds, which you should read), but at least when it comes to the languages and countries where we know The Baby-Sitters Club was translated, WorldCat is a better place to start an open-ended search than Amazon.

One more thing you should keep in mind about WorldCat: they take what they get from those libraries in terms of metadata. Sometimes it’s a total mess, with metadata obviously and painfully wrong – like claiming a book with a transliterated Russian title, published in Moscow, with all-Russian metadata and no translator, is in English. If you’re lucky, it’s just incomplete. In either case, when you search for something, chances are that there’ll be multiple separate records for the same book, due to minor differences in the metadata.

For starters, I went to the advanced search page, typed in Martin, Ann M. into the author field, and ran the search. Selecting the correct author facet left me with a bit over 3,200 results.

Scrolling down to (and expanding) the Language facet, I saw there were over 2,000 English hits. No surprise there.

I started with Polish: 7 results. Joanna Byszuk had mentioned reading them as a child, and I was itching to get my hands on Wspaniały pomysł Kristy (Kristy’s great idea), Claudia, telefon i człowiek-widmo (Claudia, the phone, and the ghost-man), or Cała prawda o Stacey (The whole truth about Stacey). Unfortunately, the only library included in WorldCat that had a copy was the National Library of Poland in Warsaw. It was hard to imagine that an interlibrary loan request to mail those books halfway across the world to California would get me anywhere.

This became a recurring theme. Kristy a její klub: Kristin bezva nápad? National Library of the Czech Republic in Prague. La Mary Anne salva la situació? Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid. Then there were some records that either point to a good story, or a strange cataloging error. How is Harvard the only WorldCat library with הרעיון הגדול של קריסטי / ha-Raʻyon ha-gadol shel Ḳrisṭi? Why are Norwegian translations like Kristys gode idé only available in the Newark Public Library? Why is Stacey loca por los chicos (and many other Spanish translations) available in the Biblioteca Nacional de España, Red de Lectura Pública de Euskadi in the Basque Country, and… the Anchorage School District? And I found other ghostly traces of books: Claudia dan Janine sie besar kepala (which Google Translate assures me is “Claudia and Janine are Big Heads” in Indonesian) and Kristy vs kelompok sok pamer (“Kristy vs. the group showing off”) are listed as results, but aren’t shown as being available in any library at all.

If you want Baby-Sitters Club books you can actually get your hands on, you’re limited to a much smaller set of languages than you might think at first. (For Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Thai, it was Ann M. Martin’s other works, like A Corner of the Universe and Doll People, that got translated.) We’re talking Spanish, French, Italian, German, and Dutch if you’re lucky. One thing I like about WorldCat is the integration with booksellers. On the page for an individual work, in the upper right, there’s a widget that queries the API for Amazon.com (crucially, not all international Amazons, where you’re more likely to find some of these translations), AbeBooks, Barnes & Noble, Better World Books, iTunes, and a few other sites where you can potentially buy the book. If WorldCat “finds” it using the metadata in that record, it’ll display the price. (Of course, if the metadata in the record is wrong, you may end up following the link to another book entirely, which happened more than once.)

I don’t get the pricing for Baby-Sitters Club translations. Really, I don’t. Sometimes they’re dirt cheap: I picked up five Dutch translations for $1 apiece (before shipping, which is the real killer if you’re in the US; $5 turned into $30, all said and done). One of those books, Een nieuwe stijl voor Inge (AKA “Mary-Anne’s Makeover”), is now available for $40 from AbeBooks and $60 from Amazon. I’ve seen books – without any obvious special features, like a signature from Ann M. Martin, or a lock of her hair, or her personal phone number – going for over $200 before shipping. I’ve even seen as much as $400.

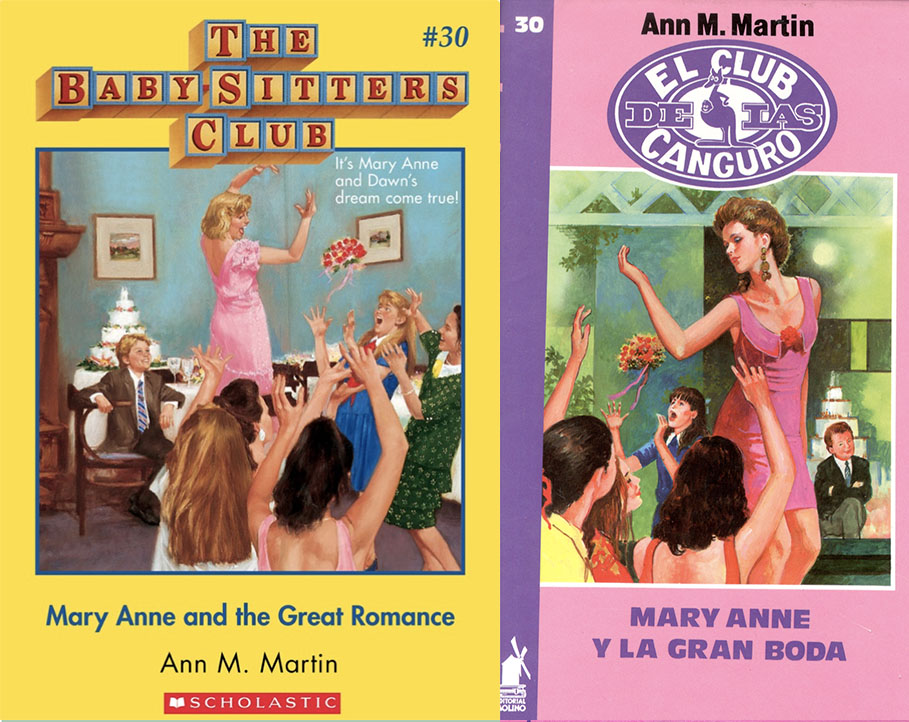

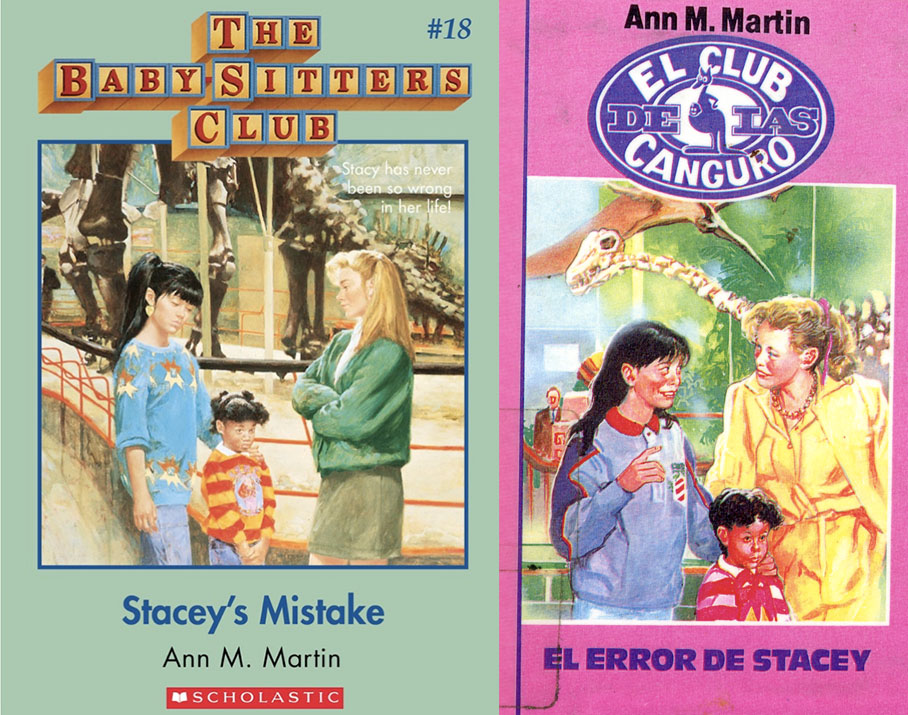

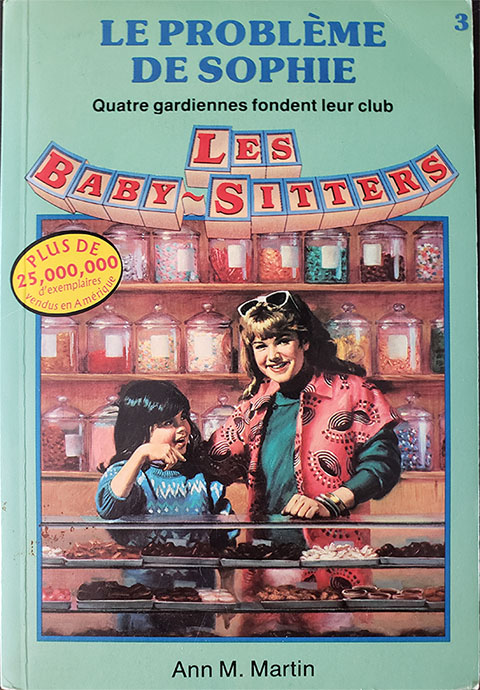

I had a little extra money after Christmas, but not that much. So I looked for cheap books, then on AbeBooks, looked for additional books from the same booksellers (an option feature you get when you add a book to your cart), hoping that combining international shipping might make it slightly less painful. Other than the five Dutch books that I couldn’t resist, I largely focused on Spanish books so I could read them. Also, the Spanish books have the best translation of “The Baby-Sitters Club” (as “El club de las canguro”), and the best logo to match. And they even do a derivative logo for the mystery books.

What’s more, the Spanish cover art takes the US cover art and turns it up to 11 in terms of being utterly 80’s/90’s-tastic.

I was surprised by what I often didn’t find in the metadata for these translations: the translators! I expect that to be a fundamental piece of metadata about any translation, about equal in importance to the author. Not when it comes to mass-market children’s literature, I guess. The hit-or-miss translator information was going to make it tricky to figure out how many times these books had been translated. Sure, there were new editions of the books with more-contemporary cover art (the members of the new Club de las Canguro are so much cooler than me), but especially since the modernizing edits to the original English books stopped after about the first 10, is there any reason to expect that publishers would’ve invested in all-new translations?

The Data-Sitters Club may have been my great idea, but the project (and its funding) belongs to all of us now. So while I indulged in a handful of translations on my own dime, I wanted to wait until our next meeting to consult with the rest of the data-sitters on how we should spend the rest of the money for the Literary Lab. I described what I’d found in my WorldCat browsing: lots of translations locked up in libraries with no obvious way of accessing them, and godawful shipping rates to the US from Europe (though I’d started making inquiries with a network of potential summer “book mules” to help out with Italian and Spanish translations). French, though, seemed like an appealing option. Katia had managed to find copies of recently-published French translations on Amazon. There were some used bookstores in France that had lots of copies of 90’s translations, and were generous with combining shipping. But what’s more, one of the earliest translations of the Baby-Sitters Club series was done in Quebec, in order to enable distribution of the original English versions of the books into Canada. And even more: there was a Belgian translation after the Quebecois version, but well before the translation in France. We’re talking up to four different translations for some of the French books: 90’s Quebec, 90’s Belgium, 90’s France, and recent France (if it was, indeed, different) – and the Quebec ones could be mailed to Katia in British Columbia for non-exorbitant shipping. And still more: in the Ann M. Martin papers at Smith College where my friend Shannon Supple works as the curator of rare books, there’s a copy of a draft French translation of Mary Anne Saves the Day from Quebec, and a letter from the Quebec publisher!

French clearly seemed the way to go. There was just one problem: I don’t really read French (beyond what anyone with some knowledge of historical linguistics and Romance languages can sort out). I can handle the computational end of text analysis on French, but I’m not the right person to solve any mysteries here (as I was gently reminded by Maria in DSC #3).

Luckily, Roopsi knew just the right person. “I bet Lee would be interested…”

From: Roopika Risam To: Katia Bowers, Maria Cecire, Quinn Dombrowski, Anouk Lang Date: January 7, 2020 at 4:52:29 PM

Dear DSC friends.

I’m pleased to introduce Lee Skallerup Bessette, whose response to my email was:

“YOU DO KNOW THAT I HAVE WRITTEN ABOUT FRENCH VS QUEBECOIS TRANSLATIONS RIGHT?

OMG I WOULD LOVE TO.”

Welcome to the DSC, Lee!

All best,

Roopsi

Lee#

When I first saw the announcement about the Data-Sitters Club, I was not so secretly jealous of those lucky few who were participating. I was obsessed with The Baby-Sitters Club books when I was younger. But, I thought, they’ve got everything covered. What could I possibly offer? So, I kept quiet tabs on the goings-on of the project and went on with the other 27 or so writing and research projects I have going on.

Little did I know that they would become interested in the various foreign-language translations and publications of the books, and, what do you know? I happen to have written a dissertation on translation, focused specifically on various French-language markets, as well as first-hand knowledge of Quebec language and culture, including publishing. Would I be interested in helping them look into the various (Quebec, France, Belgium) French translations of the series?

Folks, this is academic-nerd dreams come true.

First thing I did was to head over to the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) website to search for the Québécois translations of the books. I knew they would be in there, as any and all books published in Quebec have to be legally deposited there. While the library itself has been around for 100 years in one form or another (EXACTLY 100 years), the law that required any and all publications in and about Quebec moving forward was enacted in 1968, at the height of the Natonalist movement in the province. The idea of and for this library was to make history and knowledge accessible to all in Quebec, in their mother tongue. So while Canada has its own National Library and Archives, Quebec wanted to ensure the preservation of their own history, accessible to their own people.

The remnants of the first-wave Nationalist movement also formed the infrastructure that facilitated the rapid publication of these books for the Quebec market, almost at the same rate they were coming out in English, one per month. Canada, in response to Quebec’s Nationalist sentiments, created funds to support the translation and publication of works from each official language into the other. Literary translation flourished, and so did the number of translators. This meant that in the late 1980s, there was a rich network of talented and skilled translators.

The metadata on the Quebec translations of the books is much better here, and there are no less than four different translators who worked on the series. This makes sense, as they were trying to match the one-a-month pace of the actual series. Three of the four translators were either authors of children’s or YA books themselves, published through Héritage, or had translated other books for the publisher, thus could be considered “in house”. But one of the names sounded familiar, and a bit of digging revealed why: it could be that the Nicole Perron who translated Baby-Sitter Club books is the same Nicole Perron who is the mother of Yann Martel (author of The Life of Pi), co-translator of the book with her husband. Now, there could be two Nicole Perron’s who do translation, but really, this is an interesting development: respected literary translator who got her start translating YA.

Gotta pay the bills somehow.

This is also why the metadata on the translators was so well-documented: it was important in terms of getting paid, later, in terms of sales and reprints. In order for the translators to remain in the business of translating, they needed to be paid. It also represents Canada’s (and Quebec’s) efforts to recognize and reward the work of translators. And while translations of Degrassi or Baby-Sitters Club wouldn’t be winning any awards (insert commentary about “high” vs “low” literature here), nonetheless, this was important information that Quebec and Canada has worked hard to try and preserve, post 1960s.

YA in Quebec has a long history, and with various changes to the language laws and curriculum, including that all textbooks and other assigned materials in Quebec schools having been written and published in Quebec. This meant there were no fewer than 12 youth book publishers in Quebec when the French-language version of the Baby-Sitters Club was published. Quebec knew the importance of representation, so put their laws and resources into home-grown literature for schools and for kids. Interestingly enough, Héritage was singled out in an overview of YA publishing in Quebec during the 1980s as being the only publisher doing YA series in translation; they were also publishing Degrassi books (a wonderful late-1980s uniquely Canadian pop-culture reference), Choose Your Own Adventure books, and Goosebumps, among others. It has such an importance that the BAnQ has developed a center within the library devoted to Quebec youth literature: Centre québécois de ressources en littérature pour la jeunesse (CQRLJ).

Maybe the Héritage archives are there…

This knowledge of Anglophone YA series reflects Quebec’s proximity to English-Canada and, of course, the United States. Quebec also had a long history of translating and adapting cartoons for the Quebecois market, most notably, The Flintstones and The Simpsons. The Flintstones, in particular, are an interesting and illustrative example: it aired in both French and English simultaneously in Quebec (on different local channels, of course) at noon, and we all watched while we were home eating lunch. Except, all of the Flintstone character names had been changed to more Francophone names, except for Fred. When I went to school in French at Sherbrooke, we had a hard time figuring out that we were, in fact, talking about the same show, despite my saying “Barney” and them saying “Arture.”

I haven’t gotten my hands on the Quebecois Baby-Sitters Club books yet, and I don’t ever remember seeing them growing up. Then again, that’s not that surprising. I grew up in the western suburbs of Montreal, which were still largely Anglophone. There were few French books at the bookstores I frequented, and if the French-language sisters of the books I was reading were anywhere, they would be in the French section, and why would I look there? I’m planning, now, to head out to the BAnQ and request to see their collection, to read them and see what impact having up to four different translators working on various translations almost simultaneously. As I understand it, the stories now take place in Quebec, and I’m curious where the fictional suburb is meant to be: South Shore? Laval? East End? Certainly not where I grew up (see: Anglophone area). The publisher also still exists, and maybe they still have the archive of how these books came to be in French.

I wanted to see if I could gage if the books had any sort of lasting impact. I went to Érudite, Quebec’s own JSTOR, to see what I could find, and outside of a celebrity profile that says that she voraciously read the books as a teen, and a review of the series from a 15-year-old from another magazine, there is little trace of the books. That isn’t to say they weren’t popular, as they kept being published well into the 1990s, so they must have made the publisher money.

Finally, being impatient (and also needing something to do while watching hockey), I started searching AbeBooks for copies of the Quebec translations. I can easily save on shipping costs by sending them “home” to my mother, but if they happened to be for sale at a Montreal used bookshop, I could send her on a field trip. I narrowed my search parameters by limiting myself to book sellers in Canada, and by searching for just Héritage as the publisher. Turns out, one used bookshop in Hearst, Ontario, seems to have an almost complete set of the books. Northern Ontario is home to a number of French-Canadian communities, formed during the great migration of French-Canadians during the late 19th and early 20th Century; the Catholic Church encouraged/required large families to resist assimilation, as well as a slavish devotion to an agrarian lifestyle meant that there wasn’t enough hereditary land to go around, causing French-Canadians to migrate west and south. Hearst is one of those communities, and the used bookstore, Librairie du Nord, specializes in Francophone books. I imagine a young girl growing up in Hearst collecting the series, keeping it for years and years, and then selling the whole thing off when she moved away.

I also want to know if they’ll give me a deal if I offer to buy the whole collection that they have.

The more I think and write about this, the more I feel like I’m coming full-circle, and this is coming at just the right time: my dissertation supervisor wrote about YA books in translation, I have been itching to have an excuse to go digging in archives again, and I just finished a first draft of a manuscript of my own experience growing up where I did. Part of the reason I wanted to is because I never saw where I lived described and depicted in literature and other pop-culture. Stoneybrook was so unlike the suburbs I grew up in that sometimes I struggled with the setting to the distraction of the story. I wonder if the French version would have resonated with me more growing up, if only because it would have perhaps been a little bit more like home.

See, Quebec did get it right: representation does matter.

Quinn#

Okay, so maybe we haven’t solved any francophone mysteries yet. But we’re on our way, now that we’ve got Lee as our Mallory – in the “keeper of the mystery journal” sense, not the “ugh… another Mallory book?” sense! It’s good to be back in the non-English DH business.

Stay tuned for Data-Sitters Club Mystery #2…

Suggested Citation#

Bessette, Lee Skallerup and Quinn Dombrowski. “DSC Multilingual Mystery #1: Lee and the Missing Metadata.” The Data-Sitters Club. January 23, 2020. https://doi.org/10.25740/gd239vj6434.