DSC #2: Katia and the Phantom Corpus#

by Katherine Bowers

December 12, 2019

https://doi.org/10.25740/nj242yt4186

https://doi.org/10.25740/nj242yt4186

It was a dark and windy fall night, with rain lashing at the windows, when I settled in to do some reading and began working my way through the Baby-Sitters Club series. This kind of weather is not surprising because I live in Vancouver, Canada, where it rains most of the year. What was surprising was that I was reading Baby-Sitters Club books again. I’m an Assistant Professor of Slavic Studies and a lot of the time you will find me reading long Russian novels, which is what I research and teach for work. I last read a BSC book circa 25 years ago, but I started rereading the series on that rainy night because of the DSC, the Data-Sitters Club, a group I’ve joined that is working on creating a comprehensive, colloquial guide to digital humanities computational text analysis.

What is the DSC? It all started with Quinn’s great idea. The DSC is a group of scholars who are interested in and have varying levels of expertise in digital humanities and computational text analysis, but who have come together to collaborate on a digital humanities guide centered around the Baby-Sitters Club books, which were published by Scholastic from 1986-1999. To learn more about us, read Chapter 2.

My involvement with what became the DSC had started about a month earlier when Quinn, Roopsi and I had started talking on Twitter about a corpus of BSC books Quinn had found online while she was on holiday in Vegas. I had read BSC books obsessively as a kid – to the point that I read them way beyond what their typical age range was and was book-shamed in my 7th grade English class by my teacher who told me to read more “elevated” things. It’s true that BSC books were maybe not so “elevated” as what she wanted us to read, but, for me, a kid who had recently moved to the US and was figuring American middle school out for the first time, BSC books were comforting in their formula and their tales of American suburbia that always had a happy ending. (And, anyway, I’d already read the books assigned for 7th grade English.. I’m kind of a bookworm). What I realized when we had our first DSC Zoom meeting to talk about the project was that, while my knowledge of the BSC series is somewhat misty, Roopsi’s is impressively encyclopedic. And so, as Quinn fleshed out our corpus, I started reading so I would have better knowledge of our corpus (and, let’s face it, reading BSC books is not something you really have to twist my arm to do).

Just how did Quinn manage to find most of the Baby-Sitters Club books while on vacation, you might ask. Quinn and I share a love of the Russian language, and one of the perks of studying Russian is that you learn how to find things. “I always wished I could get away with making posters for first-year Russian that read ‘Learn the one verb you need to find anything online!’ – that’d fix our enrollment problems!” Quinn jokes. (That verb, by the way, is скачать “skah-CHAHTS”, and if you add it to your query on a Russian search engine like yandex.ru, you might be surprised at what you can find sitting on the open web.) But there’s a difference between what you find in assorted corners of the internet that aren’t indexed by American search engines, and what you’d get if you “did it right” by scanning and OCR-ing in-copyright books for private research use, with manual correction as necessary. (Cracking the DRM on e-books is illegal even if you’ve purchased the e-books, are just trying to get a text file for research use, and don’t redistribute the text files.)

To start with, I bought a bundle of the first four books as ebooks. The corpus wasn’t in place yet, and I was just so excited to start reading! I can finish a BSC book in a little less than an hour, reading them is comforting, even today (I think because of the time in my life when last I was reading them and how important they were for me then), and, as the DSC got started up, I was finishing up my monograph (which is about Russian realism and the gothic genre) and actively in search of stress-free pleasure reading that would help me get to sleep in the evening. These three factors all contributed to the fact that before I knew it, I had read all four, and was ready to move on to no. 5, Dawn and the Impossible Three. I was really excited to reread this one because this was the one I had read the most as a kid; it was the only one I had owned and not just checked out from the public library.

I opened up the corpus copy, started reading, and:

A he <BZZT!> Baby-sitters Club. I didn’t start it and I don’t run it, but I am its newset member… uprooted from hot, sunny California and trans- planted to cold, sloppy Connecticut <BZZT!>.

The door was flung open by Claire, the youngest Pike. She loves answering the door and the phone.

“Hi, Clairer <BZZT!> I said brightly!”

Maybe that corpus would be okay for computational analysis at scale, but it was not okay for my brain, especially when reading quickly. The errors that crept in when whatever entities were responsible for this text did OCR (Optical Character Recognition) on scans of book page images – they were like nails on a chalkboard as I tried to read. And then, in some of the books, like a slash across the text, there was this: “ClHHEfflfflB”. Or this: “ClHSIEffllHE”. Or this: “HI HE I] [E] El / j =j. / / /”. WTF was this garbage?

And it got worse. Sometimes, there would be a wall of gibberish, with faint traces of intelligible words:

~Thur6dflu, September 2tf

&6+zrdau X baba6flt {or Kr?6iil6

iTHta. brom^DavtdtehaeUK^tu-told

U5 -to wn+e to -ttY2 Bflbu-5T-ttgT6 Sub Notebook 5o\we Could eep track of tinu prdolem6 we h&d wT^^bu-iTte) aubMft, bo -ftkTna care dt ttMtf HwSfcl w35m+rDUbl(2 3rZltt° H<2w36 very otxd. White Kr?6+-y w35 chfoTrg rjroona nf+er -mobe +wd dephzlh+6,

When I was browsing in Lawrence Books later that week, I found an old paperback copy of no. 16, Jessi’s Secret Language, and flipping through it, the answer jumped out at me:

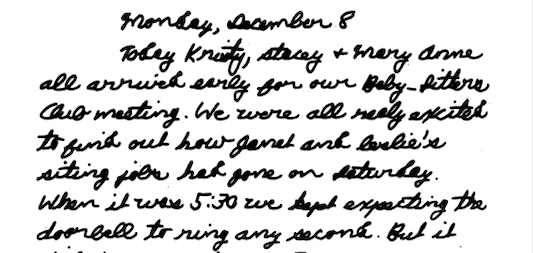

The OCR software that had been used for some of these books wasn’t able to handle the children’s building-block lettering of the chapter headers, or the Baby-Sitters Club notebook entries (or diary entries, or letters) written in the characters’ “handwriting”!

(Honestly, I wonder how easy it’d be for young human readers in 2019 to successfully read Mary Anne, Jessi, Kristy, and Claudia’s cursive writing. This is Claudia’s from no. 3, The Truth About Stacey; it takes me a bit to get through it - and I’m used to reading 19th-century Russian cursive!)

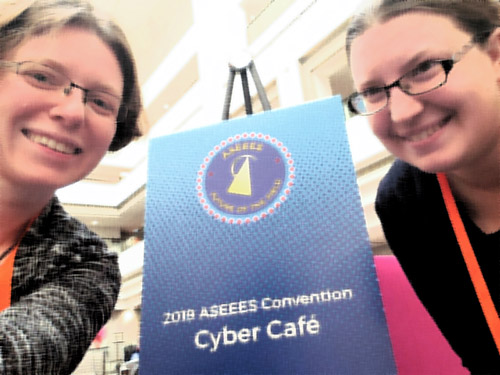

Quinn and I met up at the amusingly retro “Cyber Café” sign at the ASEEES Convention in San Francisco in November. (ASEEES is the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies - the biggest Slavic conference in North America, which happens every November). The Cyber Cafe sign seemed nicely thematic because it looked like it had fallen out of some kind of time warp from the mid- to late-BSC books. We took a selfie to mark what we jokingly called “DSC Slavist Super Special” (obviously) and sat down to talk about the issues I’d been having with the corpus Quinn put together.

The thing about Quinn’s corpus is that it’s from a lot of different sources. They didn’t all use the same software to digitize the texts, and didn’t have the same post-processing conventions. In some sense, the OCR gibberish was better: you could see that something had gone wrong, and knowing something is wrong is the first step in fixing it. But in some texts, the traces of OCR failure were just erased. Instead of garbage, there was nothing. Sometimes you can’t necessarily tell that anything is missing, like the transition between chapters. Sometimes, there’s a gaping void, like at the end of Baby-Sitters Club Super-Special 9: Starring the Baby-Sitters Club, where the last words in the text file are:

When I first sat down to write the rough draft, my friends gave me a hand once again. I asked them for their final thoughts and observations. This is what they wrote:

Omitting long strings of obviously bad OCR isn’t the world’s worst approach: sometimes when you’re doing OCR, the software will try to “read” things like shadows in the margins of a book, or illustrations, giving you a block of gibberish when there was nothing meaningful there to begin with. In fact, if you’re scanning thousands of books, that kind of situation is going to be more common than books with unusual lettering in their chapter headers, or cursive pseudo-“handwriting”. The Baby-Sitters Club books are an edge case – but they’re the case we care about.

I realized I just wasn’t going to be able to read the corpus as I had planned, and so, in order to keep reading and keep my sanity, I started buying books. A bonus was that I could then turn them into our “ground truth” for comparing against Quinn’s corpus. “Ground truth” is a concept used in evaluating OCR quality: it’s typically a transcribed (or OCR’d and hand-corrected) version of some number of pages or lines, such that you can do OCR (either using out-of-the-box software like open source Tesseract OCR or OCRopus, or commercial – and sometimes better-performing – software like ABBYY FineReader) and easily compare the output with the “correct” answer that’s been verified by a person who knows what they’re doing.

Quinn’s OCR Tips#

If you need to do some OCR yourself, here’s some tips from someone who’s spent a lot of time doing it:

Actually scan your sources. With a scanner. At minimum 300 dpi (dots per inch – it’s a measure of how much detail the image captures). More like 400-600 dpi if your books include a really small font, like for footnotes. Yes, the technology is improving, and sometimes you can get better-than-total-garbage with photos from your phone, as long as they’re not skewed (taken at an angle), the lighting is good, etc., but still, most phone pictures are still only 72 dpi, and it’s hard to position your phone directly above a book and not cast a shadow. Just use a scanner.

Scan your sources in grayscale, especially if you’re going to be using ABBYY FineReader. While all the OCR algorithms actually use on binarized images (black & white – where everything in the image is either black or white, according to some threshold you or the software defines), you can go from grayscale to B&W, but not the other way around. Even though the OCR algorithm itself involves a binarized image, the algorithms used for layout analysis (i.e. figuring out where the text is on the page, whether it’s one column or two, whether there’s tables or running headers or page numbers, etc.) are more nuanced. Also, both ABBYY FineReader and the open-source Tesseract software include pre-processing steps before they perform the OCR, including binarizing images using a sensible threshold that cuts down on the noise in the image. For instance, if you run a B&W scan of a two-page spread through Tesseract (i.e. an image where the binarization has happened at the time when you did the scanning), you’ll end up with some gibberish from when the OCR algorithm tried to “read” the shadow caused by the binding.

The ABBYY FineReader documentation recommends color scans, but in most cases, the improvement in final OCR quality from color images vs. grayscale is negligible, and the file sizes are much bigger for color images.

Save your scans as .tif files, which are uncompressed and don’t lose any of the data in the image to make the file size smaller. A 300 dpi grayscale scan of a two-page spread of a Baby-Sitters Club book (like you’d get when scanning it, assuming you don’t want to just cut the book’s spine and run it through a sheet-feeder scanner – which is viscerally disturbing, but a much more time-efficient option) is close to 7 MB, and there’s around 80 such scanned images per book, which works out to around half a gigabyte per book for the page images. If all you want is good OCR, don’t feel like you need to keep all these image files for the long-term: you’re not responsible for library-quality preservation for the books. Once you’re satisfied with the OCR quality, you can let them go and delete them.

Use ABBYY FineReader (on Windows). Ideologically, we all (especially in digital humanities) support open-source software. Various digital humanities projects have focused on improving OCR quality for Tesseract (e.g. Laura Mandell et al’s Early Modern OCR Project which trained an earlier version of Tesseract for early modern typefaces, and the Open Islamicate Texts Initiative Arabic-script OCR Catalyst Project, which is providing a more user-friendly workflow for Arabic and Persian OCR based on Tesseract). But the fact is, while character-by-character recognition (at least for English) is basically identical between FineReader and Tesseract, FineReader does a lot of “common-sense” things that make your life easier:

End-of-line hyphens: FineReader understands that if a line ends with a hyphen, it means that the word continues on the next line. So when you export text from FineReader, it re-connects those split words.

Lines in general: Tesseract’s OCR exactly replicates the line structure of the original source. But for most computational text analysis purposes, what we care about is meaningful divisions in the text, rather than arbitrary ones caused by the inherent constraints of mass-market book layout. Paragraphs matter, not which 7-10 words happen to make up a line. FineReader gets this, and maintains paragraph divisions, but treats individual lines within a paragraph as continuous text.

Running headers and page numbers: FineReader understands that, in the vast majority of cases, what you want is just the text, not paratextual elements like running page headers, page numbers, etc. There’s an option when you export the text to remove those header and footer elements.

If you’re OCRing so much text (hundreds or thousands of volumes, by many authors, etc.) that small perturbations like page numbers won’t matter, and mostly-successful text corrections applied en-masse (e.g. to try to connect lines and remove end-of-line hyphens), Tesseract is free, open-source, and high-quality (at least for English). But if you’re doing a project like ours where you care about each individual text, it’s worth using ABBYY FineReader. The FineReader interface also makes it easy to manually transcribe portions of the text that you could potentially train it to recognize given enough time and examples, but it’s faster to just type in yourself (e.g. Claudia’s cursive handwriting). While ABBYY doesn’t offer an academic discount, many institutions have FineReader available somewhere on campus (e.g. in computer labs), and depending on your situation, it may be worth paying the $200 one-time standard license. One important caveat, though: as of 2019, the Windows version of FineReader has much better functionality than the Mac version (to say nothing of the cloud-based mobile version). If you want the nice interface for transcribing text that can’t be meaningfully OCR’d (again, looking at you, Claudia’s handwriting), you’ve got to figure out some way to run it on Windows, even if you’re primarily a Mac user (like the whole Data-Sitters Club).

Before long, we had two corpora: Quinn’s scavenged Baby-Sitters Club corpus, and the more-accurate “phantom corpus” I’d created for the 60 or so books I’d hunted down and shared with the rest of the Data-Sitters Club.

OCR evaluation#

Quinn runs another club at Stanford, which she’s dubbed the “Danger Noodle Club”. It’s a weekly meet-up for humanists who are learning Python in particular, and computational methodologies in general. They help debug each other’s code, and also spend a lot of time talking about situations where other tools might be more helpful than Python. Like most things, she organizes it last-minute, so I didn’t even realize she was comparing her corpus and mine until she sent a note out to all the data-sitters one Thursday afternoon:

From: Quinn Dombrowski

To: Maria Sachiko Cecire, Katia Bowers, Anouk Lang, Roopika Risam

Date: 11/7/19 2:51 PM

Subject: Amazing discovery for our next volume!So I was demoing OCR quality evaluation today during my Python working group using “Claudia and Mean Jeanine”, and I discovered THERE ARE CONTENT CHANGES between the clean version and the version I originally found, including both computers and fashion (ie equal attention paid to gendered tech) and removing ableist language. What’s more, there were no changes in “Mystery 29: Stacey and the Fashion Victim” (despite, presumably, including fashion language) so I guess they gave up at some point. But we can find out which point, in our next DSC volume!

I wrote back right away:

From: Katia Bowers

To: Maria Sachiko Cecire, Quinn Dombrowski, Anouk Lang, Roopika Risam

Date: 11/7/19 2:58 PM

Subject: Re: Amazing discovery for our next volume!That's so interesting!!! I had noticed that there were a few weird places where they had updated things - like in one of the first 4 books, one of them (I forget who) mentions spending her baby-sitting $$ on CDs... but that seems like something that would have been a luxury item for suburban tweens of the 80s considering CD players then were _so_ expensive. Interesting to see what things they updated and what they didn't update (I'm not sure this last question is possible to find out digitally). And I wonder if the updates stopped because the books were being written about the same time as the re-releases were coming out?

It wasn’t long before everyone weighed in:

From: Anouk Lang

To: Katia Bowers, Maria Sachiko Cecire, Quinn Dombrowski, Roopika Risam

Date: 11/7/19 3:02 PM

Subject: Re: Amazing discovery for our next volume!That is interesting. Makes you want to go and talk to the publisher and find out at what level there was an editorial policy to make updates like that, and where it was at the discretion of individual editors (or copyeditors). Speaking for myself I’d want to use the original versions in any analysis at scale, just to capture what I feel like would have been the largest readership (assuming its readership has tailed off steadily since the original publication).

Also just thinking about this from the feminist computational text analysis viewpoint, this might offer us an opportunity to think out loud a bit about how one does feminist/critical corpus construction: what the rationale might be for choosing one version over another as we construct our corpus. There are lots of principles for corpus construction out there (about which, full disclosure, I don’t know enough), but I don’t remember ever having seen explicitly feminist ones. (Feminist being an inadequate shorthand here for perspectives cognisant of critical race studies, queer theory, disability studies etc.)

From: Roopika Risam

To: Katia Bowers, Maria Sachiko Cecire, Quinn Dombrowski, Anouk Lang

Date: 11/7/19 3:04 PM

Subject: Re: Amazing discovery for our next volume!That’s super interesting - at some point maybe we could do Roopsi and the Trouble with Juxta or similar 😂

From: Maria Sachiko Cecire

To: Katia Bowers, Quinn Dombrowski, Anouk Lang, Roopika Risam

Date: 11/7/19 6:39 PM

Subject: Re: Amazing discovery for our next volume!Thanks, Quinn! Those are cool findings, and in line with some other examples from the history of children’s literature publishing. Up until the Harry Potter phenomenon, children’s publishing worked on a “slow burn” model rather than a blockbuster model of sales (which it now goes for much more, though they are still re-releasing and promoting old classics too). That meant selling the same books over many generations of readers – parents/grandparents/etc. buying for children was and is a key part of the market – and I imagine this long lifespan had something to do with the fact that it’s not uncommon for children’s lit to be updated as norms change. I’m sure this has to do with the fact that anything written for children almost inevitably gets treated as didactic, and so is scrutinized for its presumed effects on youth – and anything that might be deemed a “bad influence” is likely to get changed in a way that books for adults might not over time.

Quinn spelled out exactly what she’d done later on in the thread. She was following up on a Twitter discussion she’d had with Hannah Alpert-Abrams on OCR evaluation by actually trying out ocreval. The GitHub repo has step-by-step instructions for how to install ocreval on Mac or Linux. Then, all you need to do is use the command line to navigate to a folder that contains both versions of the plain-text file you want to compare, and run accuracy file1.txt file2.txt.

Quinn used her version as file1, and mine as file2. For no. 7, Claudia and Mean Jeanine, the ocreval accuracy report stated that there were 141611 characters and 6,905 errors, for an overall accuracy of 95.12%. That sounds like a big number, but for OCR on modern English, that’s actually not amazing.

Scrolling down further in the report, Quinn noticed some interesting things in the stats for different classes of characters. The ASCII Digits class had terrible stats (Count: 120, Missed: 95, Right: 20.83%), but some of those “digits” were just failed attempts to make sense of the “handwritten” text. (Claudia may not be able to spell, but she can write in cursive.) The ASCII Special Symbols class was also a lot lower than everything else, with 57.7% right. On the list of errors that followed in the report, the top three had to do with punctuation variants: 1122 instances of “ (un-angled quotation marks) corresponding to angled opening quotation marks, 1094 instances of “ corresponding to angled closing quotation marks, and 921 instances of ‘ (a non-typographically-fancy apostrophe) corresponding to the more typographically-fancy ‘. There were also issues with three periods and their correspondence with the ellipsis character (…), which are identical to the human eye, but distinct things to a computer.

That said, those are the sorts of differences that are easy to resolve! Quinn used simple find-and-replace in a plain-text editor (she has a lot of them installed on her laptop: TextMate, BBEdit, Atom) to change the punctuation in my files to align with the punctuation conventions in hers. And by replacing just those things I’ve described above, suddenly the “OCR accuracy” jumped from 95% to 98%, which is meaningfully better.

But Quinn and her Danger Noodle Club colleagues kept scanning the error list. There were some differences that were unsurprising: differences in spacing (additional newline characters in one file vs. another), sometimes a period being rendered as a comma (or vice-vesa), and strings of gibberish in Quinn’s texts turning into correct transcriptions of handwritten text in mine. But nonetheless, there were things that jumped out at them. In the report from ocreval:

{"Nineteen dollars even,"...}-{S}

Quinn checked the source files. In her original version:

Stacey put the money on the bed and emptied the contents of the envelope over it. “Nineteen dollars even,” she announced. She said this after one pretty quick glance at the bills and change, which is why she’s our treasurer.

Became in my version:

Stacey put the money on the bed and emptied the contents of the envelope over it. She announced the total after one pretty quick glance at the bills and change, which is why she’s our treasurer.

But there was more.

“I love it! Did you get it permed again?” became just “I love it!”

“Her blonde hair, which had been long and fluffy, was now cut to just above her shoulders.” became “Her blonde hair was now cut to just above her shoulders.”

“She pressed a few keys, waited a moment, then reached around to the side of the computer and touched something or other that made the screen go blank.” turned into “She pressed a few keys, waited a moment, then touched something or other that made the screen go blank.” (This one surprised me: I’m not sure I would’ve thought to edit out the “reaching around to the side of the computer” to account for the different dimensions and conventions of modern vs. 1980’s computers.)

One of Quinn’s Danger Noodle Club colleagues, Nichole Nomura, pointed out the equal attention paid to updating differently-gendered technologies (feminine via fashion, masculine via computers). Another, Matt Warner, pointed Quinn to Diff Match Patch as an easier way to see the differences between two texts (rather than treating it as an evaluative task for OCR quality). Conveniently, if you use the Diff demo and copy and paste the results into Word, the changes show up using Word’s track changes functionality.

DSC in Stanford’s Literary Lab#

Between the comparisons using Claudia and Mean Jeanine and Dawn and the Impossible Three (which Quinn later shared with everyone), it was clear that we really did need both the original and the edited versions of the Baby-Sitters Club corpus.

I have some research funding this year, but I’d long exceeded the “no questions asked” point when it came to ordering second-hand English-language girls’ literature on Amazon Marketplace. (Remember, I’m a Russianist.) It was going to take more resources than I could cover to get the corpus we needed.

Quinn works at Stanford, and is involved with a few projects through the Stanford Literary Lab. She’d met with Mark Algee-Hewitt, the professor who directs the Lab, soon after we started this project. He was open to it becoming a Lab project, but asked her to put in a proposal that he could review with the other directors. In our first meeting, we put together a proposal that Quinn officially submitted to the Literary Lab, requesting funding to cover a “clean” corpus. We got the response in late November: The Data-Sitters Club could be an official Literary Lab project, with funding to support the corpus-building, provided we accession the corpus into their corpus management system and use their data-sharing process for people outside of the project (really, who wants to come up with those systems and processes from scratch?), collaborate with other Lab members (we’d love to apply methods from other projects to the BSC corpus and document it all), and if we do a talk or pamphlet for the project through the Lab, it should address particular scholarly research questions (no problem, we’ve got a whole Google Doc full of those!)

The BSC had Logan Bruno as their “boy babysitter” associate member, so as a Stanford Literary Lab project, it’s only fair for us to count Mark Algee-Hewitt as an associate data-sitter. Mark is an Assistant Professor in the English department at Stanford. He has a goatee, red hair that he wears in a ponytail, and sense for fashion that makes him the Claudia Kishi of male academics. He has an amazing assortment of colorful and interesting sports coats, and a penchant for creative cowboy boots. Much like Logan, Mark has distant origins (Nova Scotia, rather than Kentucky). Unlike Logan, he’s not into sports or making a big display of masculinity. Mark did babysit growing up, with an hourly rate that would’ve worked out to $3.50 USD – similar to the $3 rate mentioned in the original books, which got updated to $5 in at least one of the revisions.

As an associate data-sitter, Mark doesn’t have to come to meetings, so it was just the five of us on our call at the beginning of December. Our conversation quickly turned to the biggest question facing the Data-Sitters Club, namely, what are our questions here, and how do we go about answering them?

Maria was surprised at our enthusiasm for her off-the-cuff responses to the changes we’d discovered (which she, centered in the discipline of children’s literature, felt were more expected than a surprise). “It feels like I’m a pundit on cable news – where I hear from you what the data is, then riff on it. I’m so not used to working with data that way; I’m usually the one who gathers it, through close reading and archival research. In digital humanities, it seems like the underlying mechanism for discovery is ‘let’s try it and see what happens’, which is different than what most traditional literary scholarship does. In those cases, we pick texts with frameworks and questions already in mind. The DSC has lots of questions for our dataset, but they’re kinda all over the place. If our research process is ‘let’s see where this takes us’, I think we should say that in the posts. Or if we’re trying to figure out specific things, let’s say that.”

“I think a key to our research process is what we’re doing right at this moment,” suggested Anouk. “Humanities training doesn’t usually involve working in a team, but all of our individual understandings of where this project might go have been enriched by the conversations we’re having in these meetings. I think a big part of this is trying to figure out how our own individual ideas fit with what we might learn from other people. We all have our research goals. But we all agree that taking the project forward as a group will be enriching, and that’s something that I think distinguishes feminist scholarship from more individualistic models of the scholar as Lone Genius.”

“I’m not very advanced in digital humanities, but the projects I’ve been working on are invariably team-based, and it’s gotten me to the point where I’m co-writing a book with someone,” I said. “Team work like that seems anathema to how we were trained to work as humanities scholars, but is integral to digital humanities practice, I’m finding. Maybe a post about how to work with a team and manage different roles and aspects of the project would be helpful?”

“I was just thinking about what you’re saying about literary scholarship and how it works, Maria,” said Roopsi. “One of the ways I think about and teach using something like Voyant is that when you’re close-reading, you’re like, ‘What’s sticking out to us as we read?’ and that’s what helps shape the research questions. Most people don’t go to the text and are like, ‘I’m going to pick my research question for the text without reading it’ – some people do, I’m not judging – but that’s not how I do things. Looking at the results, learning how to interpret the results of something like Voyant, that’s the method part. It’s like close reading: what sticks out for you for your research question? It just happens with a tool. You look at the results you’re getting, that connects with these questions you have, and that informs the actual research questions. And in some ways it’s not super different from how we do literary scholarship, it’s just that instead of close reading, what we have is ‘how do we interpret the statistics, or math, or word cloud, or collocations?’”

“I get you – but how do we know what discoveries are worth diving into more? And what things we want to present field-related background on?” asked Maria. “Do we do that every time we find something that interests us? Or are there principles that guide what we pick?”

“One way to think about it might be as an iterative process,” suggested Anouk. “We explore various things, and some of those will have traction while others won’t. Maybe that’s where the genre of the blog post is useful, too – maybe a path goes somewhere, maybe it doesn’t. Or maybe someone picks it up for further research and publication in a different form.”

“We’re getting close to the end of our meeting,” Quinn interjected. “Let’s open up our scheduling spreadsheet and sort out who’s going to be doing what between now and the summer.”

To be continued…

The author gratefully acknowledges Quinn Dombrowski for her help in preparing this manuscript.

Suggested citation#

Bowers, Katherine and Quinn Dombrowski. “DSC #2: Katia and the Phantom Corpus.” The Data-Sitters Club. December 12, 2019. https://doi.org/10.25740/nj242yt4186.