DSC Multilingual Mystery #3: Quinn and Lee Clean Up Ghost Cat Data-Hairballs#

by Lee Skallerup Bessette and Quinn Dombrowski

April 2, 2020

https://doi.org/10.25740/yx951qc9382

https://doi.org/10.25740/yx951qc9382

Dear Reader#

Dear Reader,

We’ve been writing this Multilingual Mystery on and off for the last month. During that time, Lee performed non-stop heroics for the emergency shift to online instruction at Georgetown. Quinn finished teaching her Dungeons-and-Dragons style DH role-playing game course virtually, watching as COVID-19 disrupted the lives of the characters – and the students. For more than two weeks now, the Bay Area has been on lockdown, and Quinn has been running a preschool/kindergarten for three kids 6-and-under while trying to help non-English language and literature faculty at Stanford figure out what to do for spring quarter. Lee is also working from home with older kids, and we’re both grappling with how to manage what the school districts are putting together for K-12 virtual education.

Throughout all of this, we kept coming back to writing this Data-Sitters Club “book”. We’ve had to go back and edit it in places (ballet classes are no longer happening), and we’ve felt moments of estrangement from words written less than a month before. There’s been nights when we’ve been too exhausted to do anything else, but this project has been a reassuring distraction. The topics – data downloading, web scraping, and data cleaning – may seem dry and technical, but in this strange time there’s something comforting about writing up how to have control over something… even if it’s just text on a screen.

We hope it brings you some comfort, too. If you can put it to use in some way that helps other people, so much the better – whether it’s gathering data about hiring freezes, dubious government statements, or 80’s/90’s cultural phenomena that might bring a smile to someone’s face in a dark time. And if you’re not in the mental space right now to tackle it, that’s okay too. It’ll be here for you when the time is right.

Take care,

Quinn & Lee

P.S. If you want a laugh, check out our ongoing series of Important Public Health Messages from the Data-Sitters Club.

Recap#

When we left off with DSC Multilingual Mystery #2, we had realized that metadata is going to be essential for just about anything we do with computational text analysis at scale for these translations. And in DSC #4 (forthcoming soon!), Anouk comes to the same conclusions about the original corpus in English. It was time to investigate metadata acquisition and cleaning, and the DSC Multilingual Mystery crew was on the case!

Lee#

As I mentioned in the DSC Multilingual Mystery #1, I already had a pretty good working idea about where to get the metadata we needed to be able to identify translators and other publication data for the various foreign-language translations of the series: national libraries. And, I wasn’t wrong. The Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, and the Koninklijke Bibliotheek provided me with all of the information we would need to get the information we required. Oh, and the five lonely German translations from Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.

My methodology was simple: Google the country name and “national library.” Put Ann M. Martin in the search box (thank goodness for the universal language of user experience and expectations). If that didn’t work, find the word that most closely resembles “catalogue” and click on it to find a different search box. And then, the final and least simple of the steps: export the metadata.

This is where the inconsistencies arose, with each library offering its own idiosyncratic way of getting the metadata out of the library catalogue and into the hands of users. Quebec would only let me export a certain number of results from my search at a time as a csv file. I decided to limit my search by time period, as it was easiest to limit my searches in the interface that way. So, there are I had one CSV file for each year that the books were being published. France was the easiest to export, allowing me to download my entire search (which included the France and Belgium translations) as a giant CSV file. Spain let me export a page of results at a time as XML that displayed in my browser window, which I copied into a file. Shout-out to the Netherlands for having a functional English interface…and exporting the search as a simple text file. And then Italy…Italy made me cut and paste every single entry individually as XML as there was no batch export function.

All I gotta say is that y’all are lucky I love to solve a good mystery and that I only have the mental capacity for menial tasks while waiting during my daughter’s ballet class where I found myself sitting in the most uncomfortable seat imaginable while seven different dance studios practice five different dance styles, playing seven different songs repeatedly. Sigh. I never thought I’d say this, but I miss those days.

There was often the option to export the results as a simple text file, but the challenge was that simple text often didn’t preserve the accents on letters, becoming gibberish instead, making it difficult to understand the information and data. So, CSV and XML were the closest I could get to relatively universal readability, or at least the cleanest data I could get for Quinn. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a good first start. Also, the metadata you extract is only as good as the metadata contained in the book’s library entry, and apparently no one bothered in either France or Belgium to note who translated the first handful of Belgian-French translations of the books. So while I extracted all of the data that was available, there are still some mysteries that might only be solved by either looking at a physical copy of the books or reaching out to the publisher to see if they have preserved the archives or kept the records somewhere. More mysteries that maybe we’ll be able to someday solve if we’re ever allowed to leave our houses again (lolsob).

I was also curious to see if there were other translations in common Romance languages, so I looked in national libraries in South America for other Spanish translations, as well as Brazil and Portugal for Portugese translations. I came up empty-handed, but it was worth it to look to see if there were any other translations in a language that I could recognize. Which brings up the next limitation in my search: I know English and French fluently, have six credits of university Spanish, and feel pretty comfortable given my knowledge of French and Spanish in navigating an Italian language library website. So while there are more translations, I didn’t feel like I was comfortable enough to rummage around in the national libraries of other languages.

Quinn#

I was amazed at what Lee managed to find in those national library catalog records. There it was: the answers to our question about the number of translations, and who most of the translators were! One beautiful thing about most national libraries, many museums, and various other online digital collections is that there’s often an option for just downloading your search or browsing results, which saves you a ton of work relative to trying to do web scraping to collect the same information. Before you embark on web scraping from any cultural heritage website, be sure to read the documentation and FAQs, Google around, and be extra, extra sure that there’s not an easier route to get the data directly. I’m not kidding: about half my “web scraping” consults at work have been resolved by me finding some kind of “download” button. Downloading the data isn’t everything, though: I knew that if we didn’t spend the time now to reorganize it into a consistent format that we could easily use to look things up and check for correlations (e.g. between translators and certain character-name inconsistencies), we’d definitely regret it later.

Now, it’s easy to go overboard with data cleaning. Sometimes my library degree gets the better of me, and I start organizing All The Things. (This in contrast to my usual inclination to just pile things in places and assume it’ll all sort itself out when the time is right.) With DH in particular, there’s a temptation to clean more than you need, and produce a beautiful data set that has all the information perfectly structured. It’s usually driven by altruism towards your future self or other scholars. “Someday, someone might want this.” And if the data is easy and quick to clean, there’s not much lost in that investment. But if it’s a gnarly problem, and your future use case is hypothetical, maybe it’s worth reconsidering whether it’s the best use of your time right now. If someone wants a clean version of that data in the future, it’s okay to let it be their problem. In the national library records that Lee found, there’s a lot of data like that. Would it be interesting to see the publication cities for all the translations? Sure! Would it be fun to look at differences in subject metadata? Absolutely! (I’m really tempted by that one, truth be told.) But the data for both of those is kind of annoying to clean, and not actually what we need to answer the questions we’re working on. Sometimes the hardest part of DH is setting aside all the things you could do, to finish the thing that you’re actually doing.

What I was actually doing was trying to get five pieces of information out of the data that Lee downloaded, for each book:

The translated title of the book

A unique identifier to connect back to the original book (book number, title, etc.)

Which translation series is appears in (e.g. for French: Quebec, Belgium, or France)

The date it was published

The translator

Anything else in these files – regardless of how many great ideas I had for what I might do with it – was a distraction.

But wait! We already started wondering about whether certain things we were finding were quirks of particular ghostwriters. This was the perfect time to scrape and clean a data set that could help us answer those kinds of questions, too. So before we get to cleaning, let’s see what else the Ghost Cat of Data-Sitters Club Multilingual Mystery #3 might grace us with, all over the carpet! (Sorry, readers – what can I say, we’re committed to fidelity to the original book titles, however tortured it gets.)

If you want to follow along some of the steps, but not the whole thing, you can check out the GitHub repo for this book for the data and configuration files we’re with here.

Web scraping#

I do a lot of web scraping. When I need to do something simple, quick, and relatively small-scale, I go with webscraper.io, even though it gives you less flexibility in structuring and exporting your results compared to Python. I knew the Baby-Sitters Club Wiki on Fandom.com had the data I needed, presented as well-structured metadata on each book page. Webscraper.io was going to be a good tool for this job.

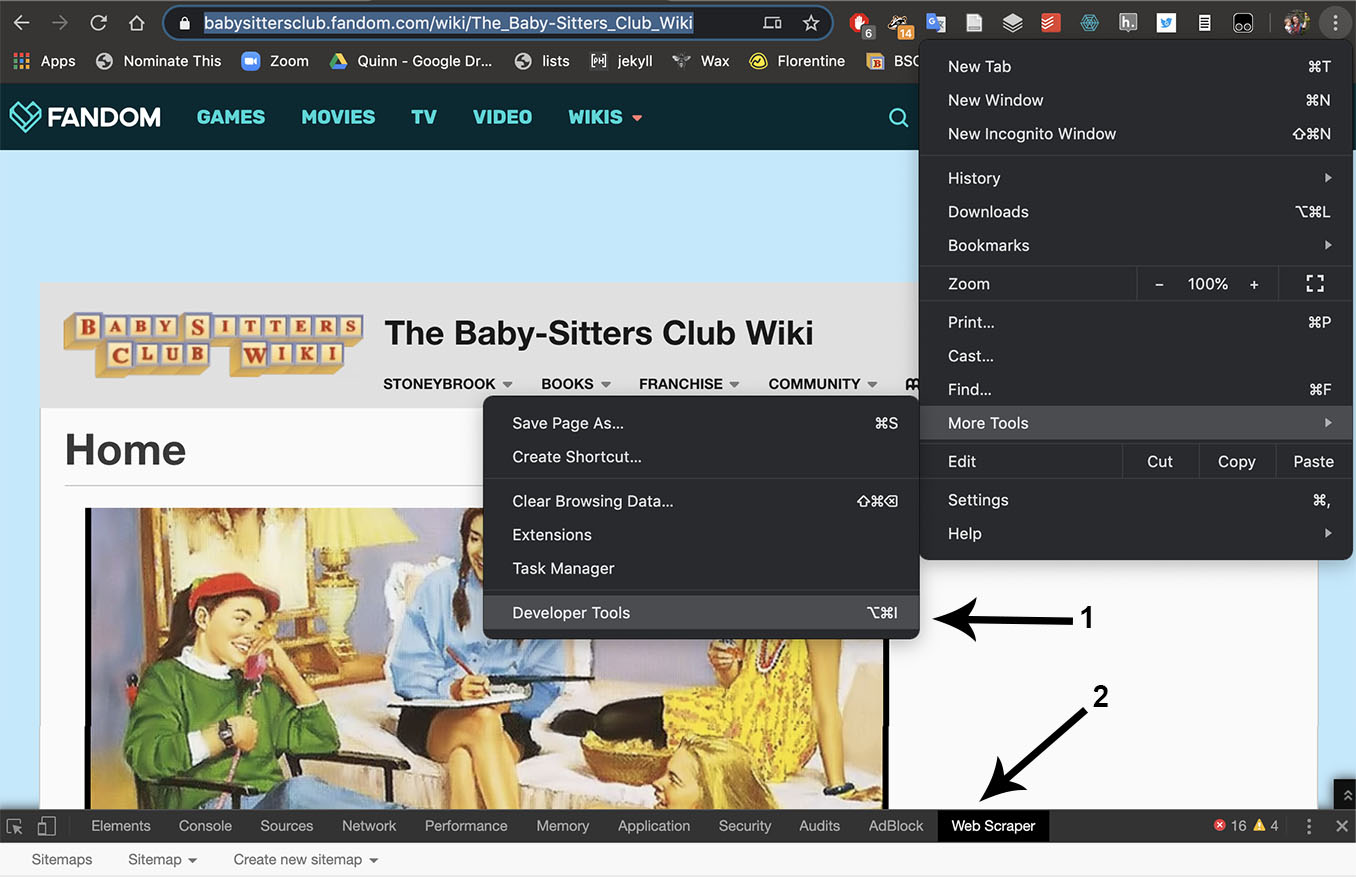

Webscraper.io is a plugin for the Chrome browser, so first you need to install it from the Chrome store. Next, you need to 1) access it in your browser by opening the Developer Tools panel, then 2) choose Web Scraper from the tabs at the top of the panel.

Creating a sitemap#

Using Webscraper.io’s menu, go to Create new sitemap > Create sitemap, as shown by arrow 3, above. (Note: if you want to import an existing sitemap, like one of the complete ones that we’ve posted at the Data-Sitters Club GitHub repo for this book, you can choose “Import Sitemap” and copy and paste the text from the appropriate sitemap text file into the text field. If you run into trouble with the instructions here, importing one of our sitemaps and playing around with it might help you understand it better.)

The first page is where you put in the start URL of the page you want to scrape. If you’re trying to scrape multiple pages of data, and the site uses pagination that involves appending some page number to the end of the URL (e.g. if you go to the second page of results and you see the URL is the same except for something like ?page=2 on the end), you can set a range here, e.g. http://www.somesite.com/results?page=[1-5] if there are 5 pages of results. In our case, though, we have eight different web pages we want to scrape for URLs, one for each book (sub-)series.

First, we’ll give our scraper a name (it can be almost anything; I went with bsc_fan_wiki_link_scraper). For the URL, I just put in the URL for the main book series, https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:The_Baby-Sitters_Club_series. If you have multiple pages (and especially if you’re putting in a range), it’s often best to start by putting in a single page, setting up the scraper, checking the results, and seeing if you need to make any modifications before you scrape hundreds of pages without capturing what you need. (Trust me – it’s a mistake I’ve made!)

Handling selectors: easy mode#

Web scraping is a lot easier if you know at least a little bit about HTML, how it’s structured, and some common elements. Especially once you get into Python-based web scraping, CSS becomes important, too. I was lucky enough to learn HTML in elementary school (my final project in the 5th grade was a Sailor Moon fan site, complete with starry page background and at least one

The way we set up a web scraper is related to the way HTML is structured: HTML is made up of nested elements, and if we’re doing something complex with our scraper, it’ll have a nested structure, too.

For our first scraper, we’re just trying to get the URLs of all the links on each page.

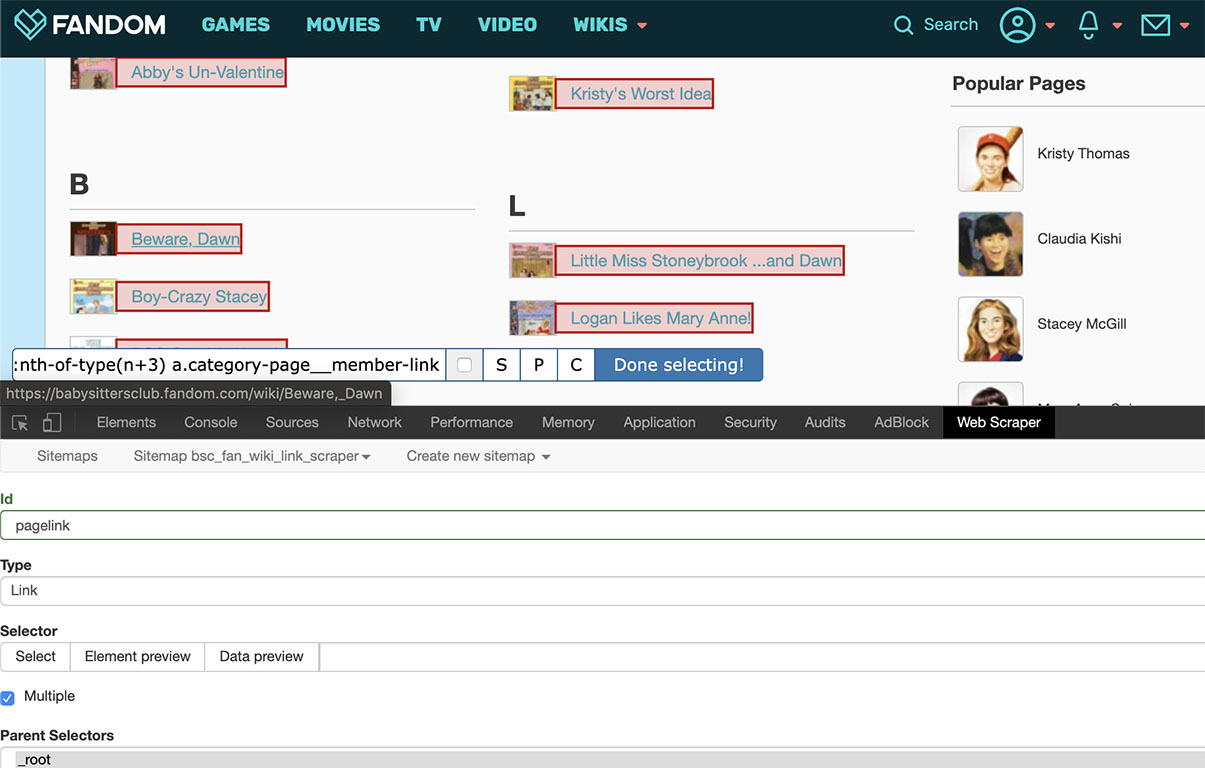

We’ll start by hitting the “Add new selector” button, which takes us to a different interface for choosing the selector. You have to give it a unique ID (I chose pagelink), then choose a type from the dropdown menu. For now, we just want Link for the type. Under the Selector header in this interface, check the “multiple” box (there are multiple links on the page), then click the “Select” button. Now the fun begins! Move your mouse back up to the page, and start clicking on the things you want to capture. After you’ve clicked on 2-3 of them, the scraper usually gets the idea and highlights the rest. In this case, I started clicking in the “A’s”, and after two clicks it picked up the rest of the entries filed under that letter, but I had to click in the results for a different letter before it picked up everything.

When everything you want is highlighted in red, click the blue “Done selecting” button. What I then had was ul:nth-of-type(n+3) a.category-page__member-link. If you’re not comfortable with HTML, you might just be relieved that the computer sorted out all that mess. But if you know how to read this, you should be concerned. <ul> means “unordered list” (typically, but not always, looks like a bullet point list), and we’re grabbing the 3rd >ul< on the page. Which, yes, is what we selected: by starting with A on the regular book series page, we’re skipping the list with character-based category pages, and the erroneous list where a wiki page name starts with the number 3. If we were just scraping this one page, it’d be fine: we’d get what we selected, which – deliberately – is not every link on the page. But what about the Super Specials, Mysteries, Super Mysteries, etc? If we start with the third list, will we be missing things?

Take it from someone who’s had to scrape (and re-scrape, and re-re-scrape) a Russian Harry Potter fanfic archive multiple times after not being careful enough: it’s almost always better to scrape too much stuff and have to do some cleaning later, than to not scrape enough stuff and have to re-do it, especially if you don’t notice until after you’ve spent a lot of time cleaning up Ghost Cat data-hairballs.

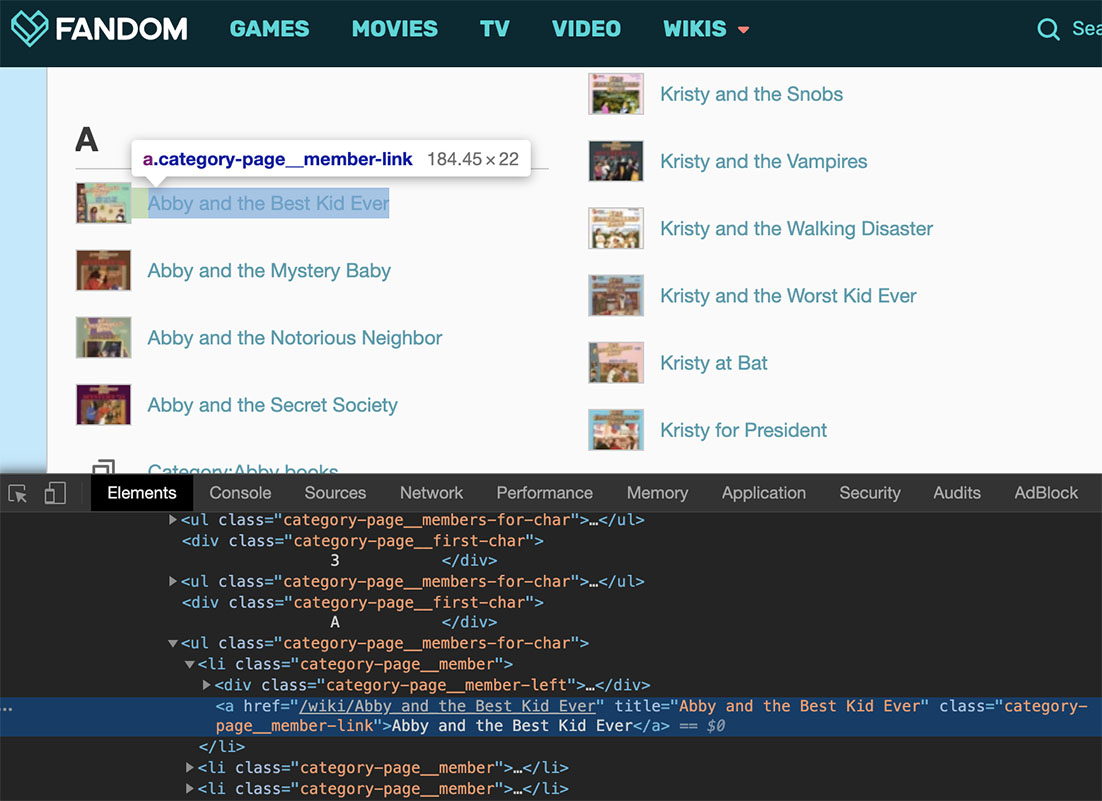

What to do? Well, :nth-of-type(n+3) is a modifier on ul, so you can drop it to get ALL THE UNORDERED LISTS. But actually, you can go one step further and even get rid of the ul part, because what you’re actually grabbing *isn’*t unordered lists, but links (in HTML, <a> for anchor) that have the class category-page__member-link. The period after the a in the selector indicates a class attribute, which you can see if you switch from the “Web Scraper” tab to the “Elements” tab in the developer toolbar.

Each link corresponds to HTML that looks something like: <a href="/wiki/Abby_and_the_Best_Kid_Ever" title="Abby and the Best Kid Ever" class="category-page__member-link">Abby and the Best Kid Ever</a>. The text Abby and the Best Kid Ever (the one that occurs between > and <) is the text that actually appears on the page. The rest is the HTML instructions used to make that text into a link. But not just any link: a link with the class category-page__member-link, which only appears with links that are part of this list of books in the series corresponding to this wiki page (Regular, Mystery, etc.) Those are the links you want. To select <a> tags with the class category-pagemember-link, click in the selector text box that reads ul:nth-of-type(n+3) a.category-page_member-link, and delete everything before the _a.

One good way to make sure you’re generally getting what you want is to click the “Data preview” button once you have something in the selection box. What you should see is all the URLs and link titles on the page, along with a _followSelectorId field that has the value of pagelink for all the links (i.e. the name you gave the link selector when you created it). What we actually need is just the URLs, so the rest is Ghost Cat hairball, but there’s no easy way to get only what we need using the Webscraper.io plugin, so we’ll take it all and clean it up later.

Click the blue Save selector button at the bottom of the interface.

```{index} single: Webscraper.io ; scraping and exporting

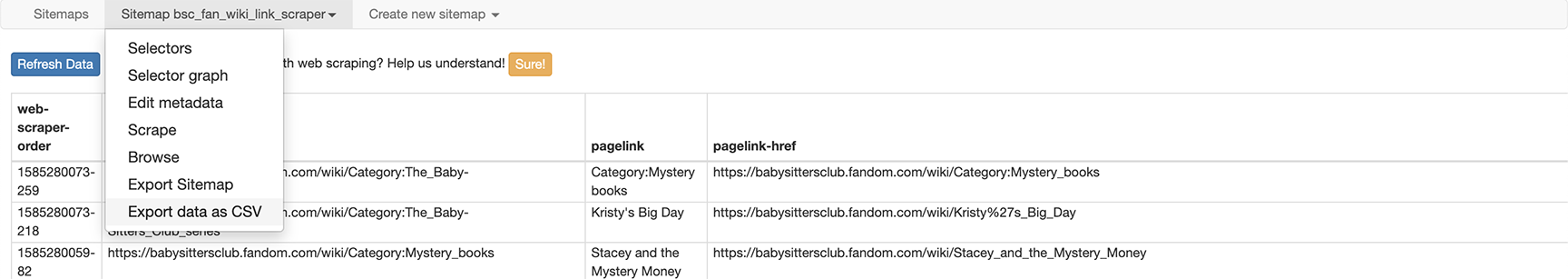

#### Scraping and exporting

Now it's time to do the scraping. In the webscraper.io interface, go to *Sitemap bsc_fan_wiki_link_scraper > Scrape*. The window that pops up has two options: Request interval and Page load delay. Request interval means how long to wait before asking the website's server for a new page, assuming there's more than one page. The thing is, if you hammer a server with requests, you're asking to get throttled: having your requests slowed.... way ... waaayyyyyyyy.... down. It's the price you pay for not having good web scraping manners. 5 seconds (5000 ms) is probably a good place to start, but if you're doing scraping at scale (tens or hundreds of pages), you still might be throttled as a bot (which, let's face it, you kinda are) if your delay is the same every time. (We can do more sophisticated things by writing a scraper in Python that can get around some of those issues, but that's a guide for another DSC book.) In this case, though, where we only have a few pages to scrape, the default is fine. As for *Page load delay*, if you have a slow connection, or are scraping a complex site that takes some time to load, you may want to increase this value. If you want to guesstimate how much it should be, time a few page loads (from the new page appearing on your screen, to everything being loaded) by pulling up pages in your browser.

Click the blue "Start scraping" button. A new browser window will pop open with the page(s) that you're scraping; don't close it, it'll close itself when it's done.

When the window closes itself, it'll take you to a page that says "No data scraped"; hit the blue "Refresh" button and your data will appear. Then go to *Sitemap bsc_fan_wiki_link_scraper > Export data as CSV*. On that page, click the *Download now!* link, and you'll download a CSV file.

If you want to edit your scraper to include multiple pages, go to *Sitemap bsc_fan_wiki_link_scraper > Edit metadata*. There's a + button on the right side of the URL field, and you can use it to put in more than one page (e.g. adding the URLs for [Mysteries](https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:Mystery_books), [Super Specials](https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:Super_Special_books), [Super Mysteries](https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:Super_mysteries), [Portrait Collection](https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:Portrait_Collection_books), [California Diaries](https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:California_Diaries_series), [Reader Requests](https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:Readers%27_Request_books), and [Friends Forever](https://babysittersclub.fandom.com/wiki/Category:Friends_Forever_series)). Then, just re-scrape and re-download.

```{index} single: Webscraper.io ; extracting URLs

Just the URLs#

We could import this CSV into OpenRefine, but honestly, it’s faster and easier to pull the CSV into Google Docs or Excel, delete the stray rows (e.g. Category:Jessi books), and copy only the pagelink-href column (which has the URLs). At this scale (fewer than 300 rows), it probably makes the most sense to just skim and do this cleanup manually, but if you search for “Category” (which will give you links that just take you to sub-categories, like “Mallory Books”), and “Karen” (which is a giveaway for books in the “Baby-Sitter’s Little Sister” book series, about Kristy’s super-annoying step-sister Karen), that should help you flag the bigger sets of bad results. There’s also random pages that accidentally got mis-tagged (e.g. at least as of when I’m writing this, “How to cosplay as Stacey McGill from the BSC”), so you do actually need to read through the list with your eyeballs, and check on any page titles where you’re unsure. You should also de-duplicate links as needed, so that you only have one copy of each link (e.g. “Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade” was tagged with both the regular series and mystery, so it appears twice.) Sorting the URLs alphabetically should help make these visible, and most spreadsheet software can easily replace duplicates automatically. (If you’re using Google Sheets, you can just go to Data > Remove duplicates to take care of it.)

All together, you should have 229 links to scrape.

```{index} single: Webscraper.io ; scraping from a list of URLs

#### Scraping ALL THE THINGS

You *could* load those 229 pages into Webscraper.io by hitting the + button on the URL field 228 times, and no doubt you may be tempted, especially if you're delegating this work to a research assistant. But resist the tantalizing purr of the Ghost Cat leading you down the path to rote labor: there's an easier way.

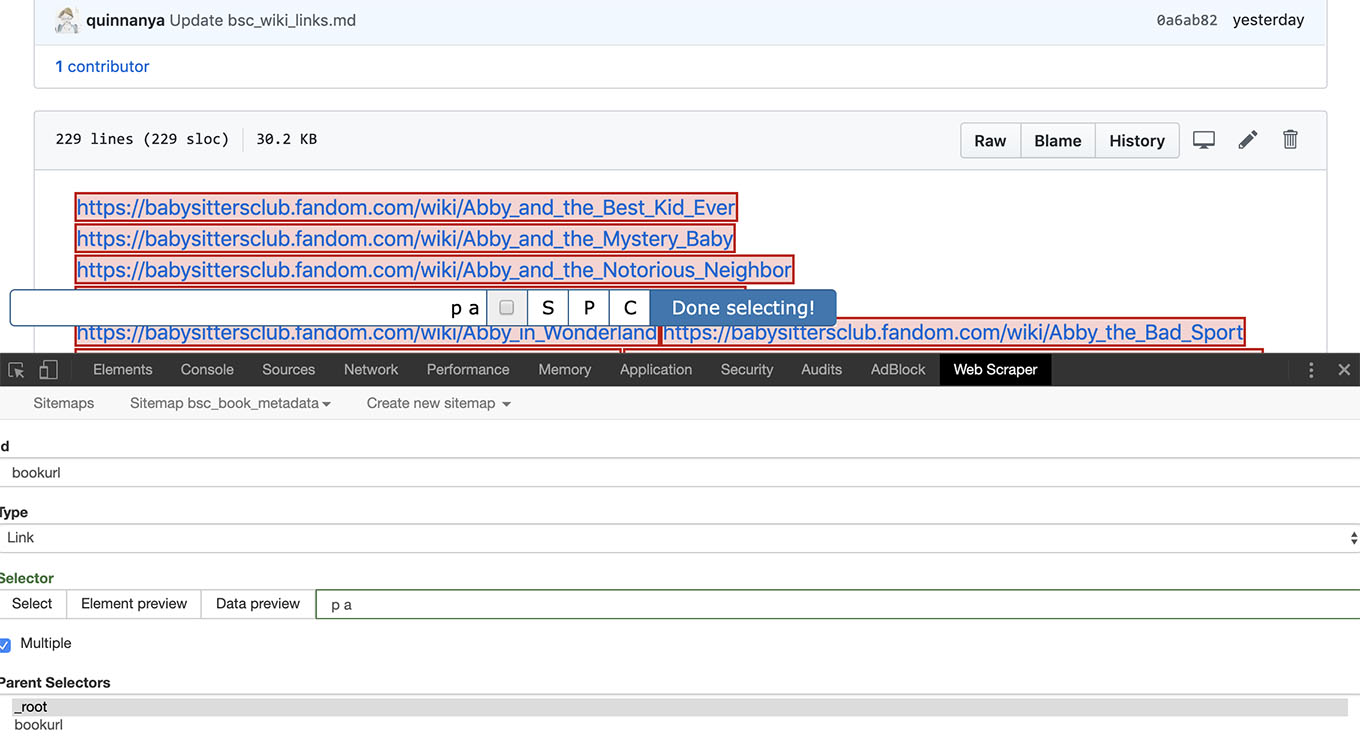

What you need is a web page with all the links you want to scrape (as HTML links, not just plain text). The easiest way to get there, as of March 2020, is to use a site like [pastelink.net](https://pastelink.net/), where you can paste the URLs from the spreadsheet you cleaned up in the last step, and it'll give you a link that you can use for Webscraper.io. The site has been around since at least 2015, though it seems at least moderately sketchy (their "news and updates" page mentions a successful purge of child abuse links in 2018 😬), and it can't handle URLs that have an exclamation mark at the end (as more than a couple BSC books do -- along with their corresponding wiki pages), but it's your easiest option if you're not comfortable making an HTML or Markdown page.

A less-dodgy alternative, if you have a GitHub account and are comfortable with Markdown or HTML, is to create a file in a GitHub repo as a place to put the URLs. This approach makes it possible to make all the URLs work, even if they end in an exclamation mark. To make a [Markdown file that you can put on GitHub (like we've done here)](https://github.com/datasittersclub/dscm3/blob/master/bsc_wiki_links.md), try this: if you copy and paste the list of URLs, one URL per line into a plain-text editor that supports regular expressions (which you can [read up on at The Programming Historian](https://programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/understanding-regular-expressions) -- they're basically a fancy find-and-replace syntax), you can search for `^(.*)$` (which translates to "grab all the characters from the beginning of the line to the end of the line") and replace it with `[$1]($1)` ("put what you grabbed between square brackets, then between parentheses"), though you may need to check your text editor documentation for whether its flavor of regular expressions uses $1 or \1 or some other notation for captured groups. If you get this to work, save the results as a .md file, and push that file to a GitHub repo, you can use the URL for that Markdown file in the next step (just like we've done, [using our wiki links Markdown file](https://github.com/datasittersclub/dscm3/blob/master/bsc_wiki_links.md) in our [book metadata scraper](https://github.com/datasittersclub/dscm3/blob/master/bsc_book_metadata.txt)).

However you put your list of links online, the next step is to create a new sitemap in webscraper.io, and put the URL *of the page with all your links*, not any of the individual links. Then, the first selector in the sitemap that you create should be set to have multiple values, and what you're selecting for is each of the links on the page.

Once you've saved that selector, click on it in your sitemap. This takes you *inside* that selector, as Webscraper.io structures things. The new selectors you add aren't selectors for your page of links, they're selectors for the *pages whose URLs are on that page of links*. For that reason, it's going to be very helpful if the links in a single list go to pages that are pretty homogenous: you want the nested selectors to be applicable to most or all of those pages. Not all the selectors I created here work for every book (e.g. the California Diaries and Portrait books don't really have book numbers), but most of the fields are relevant across the board.

```{index} single: Web scraping ; minimal structure of most websites

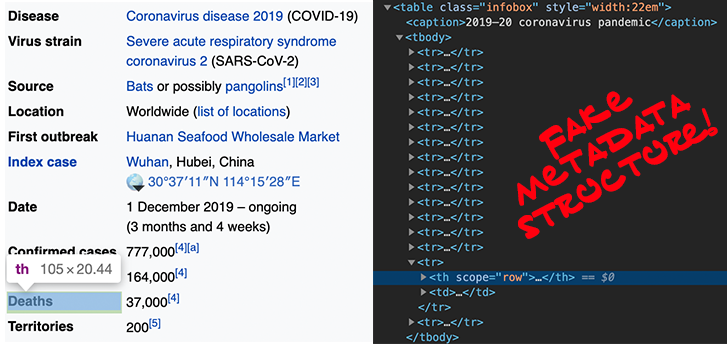

As an important side note here, wikis hosted on fandom.com are unusually well-structured and pretty remarkable for their use of semantically-inflected markup (i.e. a lot of the HTML elements include a class – as we’ve seen above – that tells you something about the content that you’ll find inside). Compare, even, to Wikipedia: even though you have what looks like structured metadata in the sidebar boxes for most articles, if you inspect the HTML, you’ll find a table with the class “infobox”, and then a bunch of table rows (

Probably the best you could do is capture the whole sidebar table, and try to (as likely as not, manually) extract the number you’re looking for. Having an HTML class that says what it is (e.g. class=”death-toll” on a

tr:nth-of-type(n+3) in your scraper if you could count on the death toll always being the third element in that sidebar. But in reality, very few websites use either totally consistent metadata, or semantic classes on their elements. In most cases, for the results to be usable, web scraping is just a prelude to lots and lots of data cleaning.

But fandom.com wikis make our lives easy! Here’s the elements I created for all the data I wanted to capture; all of them are Text type and only wikipagetext (the body text on the wiki page) has the “multiple” boxes selected, because there’s usually multiple paragraphs of text on a wiki page:

Element name |

Selector |

|---|---|

booktitle |

h1.page-header__title |

bookseries |

[data-source=’series’] div |

booknumber |

[data-source=’no. in series’] div |

bookauthor |

[data-source=’author’] div |

bookcoverart |

[data-source=’illustrator’] div |

booktagline |

[data-source=’tagline’] div |

publication |

[data-source=’date’] div |

wikipagetext |

.mw-content-ltr > p |

Now, if you want to make your life easier, omit the wikipagetext element. What I initially wanted to get out of it was the “Dear Reader” section for the books that have it (e.g. what is the wholesome, relatable message at the end of Stacey’s Big Crush, where she has a crush on a student teacher?), but there’s no HTML class to indicate that section, and it’s not like the book synopses are reliably 5 paragraphs long, so that you could count on “Dear Reader” being the 6th. But because this element has multiple values, and each one gets saved as its own row in the output file, it’s going to be a pretty gross data-hairball.

Once you’ve set this up, run the scraper, download the results, and you’ve got a brand new Ghost Cat data-hairball to clean up in OpenRefine… in addition to all those records from the various national libraries.

```{index} single: OpenRefine ; installation

### Got Ghost Cat Data-Hairballs? Call OpenRefine.

When you need to clean up metaphorical data-hairballs from an imaginary Ghost Cat, you need a tool with a fairytale story. [OpenRefine](https://openrefine.org/) started life as Freebase Gridworks, became Google Refine when its parent company was acquired, and then when Google stopped supporting it, it became an open-source project called OpenRefine, and, in 2019, got $200,000 from the Chan Zuckerberg (yeah, *[that Zuckerberg](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Zuckerberg)*) Initiative to fund its development in 2020 as "Essential Open Source Software for Science". And while they don't use a Humanities-inclusive Wissenschaft definition of "science", I'm inclined to agree: OpenRefine has been essential for a lot of my computational text analysis work.

Download and install the software as you usually would, [from their website](https://openrefine.org/). If you're on a Mac, you'll have to deal with the "Unidentified developer" warning message; just Ctrl+click on the OpenRefine icon and open it from the menu that appears in order to bypass that.

For the Ghost Cat data-hairballs we're working with here, the default settings for OpenRefine should be fine, but once you get into the thousands or hundreds of thousands of records, using OpenRefine will be torture if you don't [increase the software's memory allocation](https://github.com/OpenRefine/OpenRefine/wiki/FAQ:-Allocate-More-Memory).

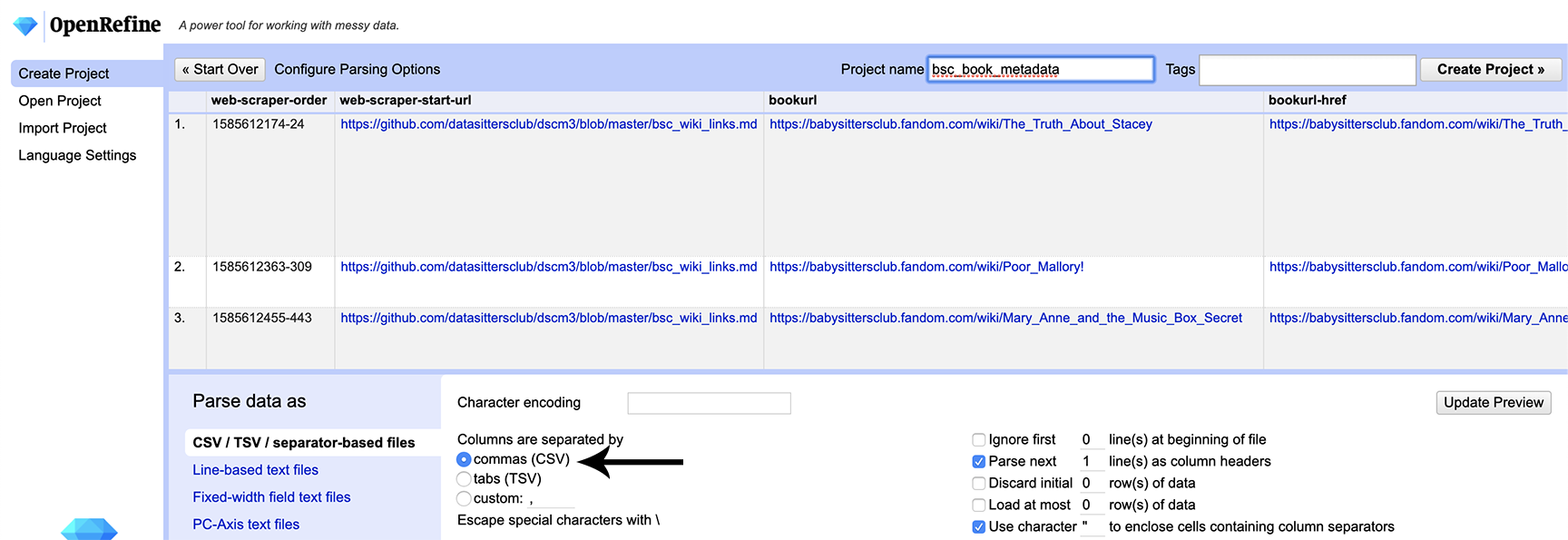

One funny thing about OpenRefine is that you launch it as an application, but what it does is open a browser tab. At least once a week, I can see the OpenRefine diamond icon among my open applications, but for the life of me I can't find the tab it's running in -- or maybe I closed it -- so I shut it down and restart it to launch a new tab. When it launches, the tab it opens takes you to an interface for creating a new project by importing a file. Let's start by uploading the file we just downloaded from webscraper.io, with all the information from the BSC fan wiki.

After you upload it, there's a screen where you can configure the import. It makes its best guesses, but those can be hit or miss. If yours looks wonky, make sure that the option is selected for columns to be separated by commas:

Once you’re happy with the preview, click the “Create project” button in the upper right. This takes us to the regular OpenRefine screen.

#### Step 1: Getting One Row Per Book from the Fan Wiki Data

```{index} single: OpenRefine ; reordering rows

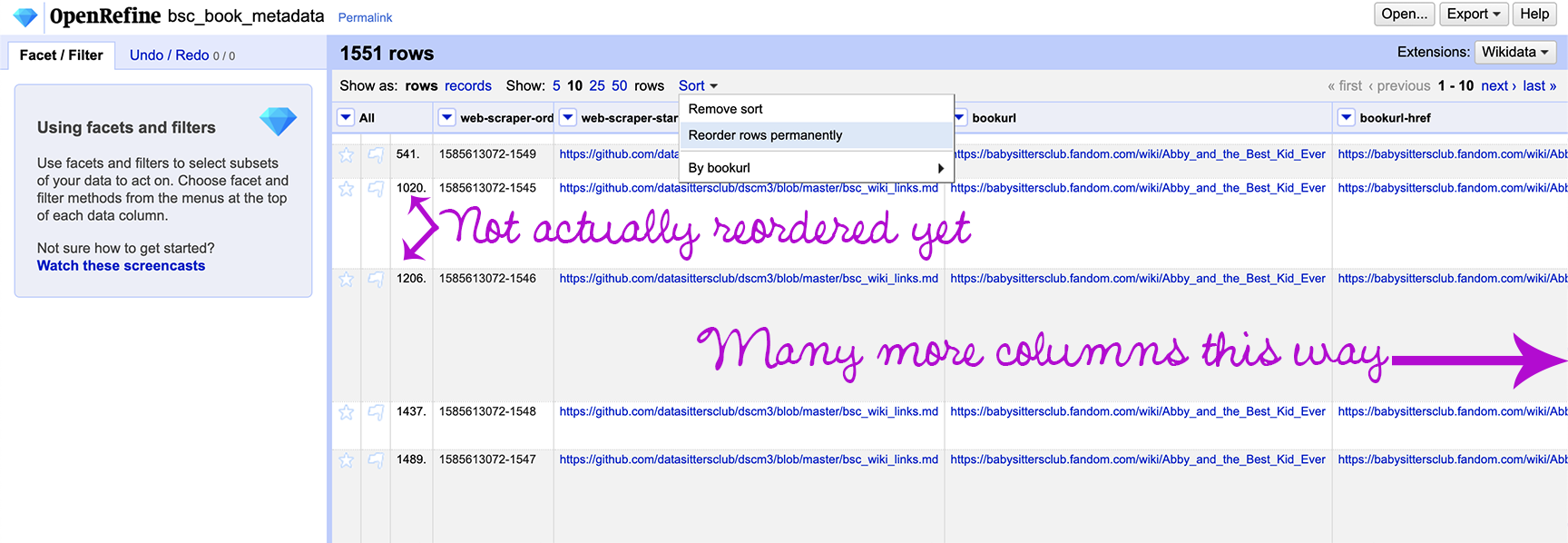

You may notice that the lines in the file that you uploaded seem to be in a random order: webscraper.io doesn’t scrape in the order you might expect, in alphabetical order like you specified. We’ll start by sorting by the URL of each page you scraped data from. Click the downward-facing arrow next to the bookurl column header, and choose “Sort” then “OK” in the box that pops up. Now your results are clustering by the book they’re associated with (starting with Abby and the Best Kid Ever), but if you look at the third column from the left, you can see that this view is just a display for your benefit: the data itself hasn’t been re-sorted. We can change that by clicking on the down arrow next to Sort above the cells, and choosing “Reorder rows permanently”. This changes the row numbers associated with Abby and the Best Kid Ever to 1-7.

Having the data permanently reordered this way makes it possible for us to clean up one part of this hairball: the fact that there’s a row for every single paragraph of text on the wiki page, and all of those rows are identical except for the initial web-scraper-order column and the final wikipagetext column. What we want here is to merge all of those paragraph-cells into a single cell, with a single row for each book.

First, delete the web-scraper-order column by hitting the arrow to the left of its name and choosing Edit column > Remove column. You can also delete the* web-scraper-start-url* column, which is the same for all the rows, and the bookurl-href which should be redundant with bookurl.

Next, what we need to do is called “Blank down”. When you have a bunch of rows next to one another that repeat data in almost all of their cells, blank down deletes the repetitions. Click on the arrow to the left of every column name except for wikipagetext, and choose Edit cells > Blank down. The first instance of each value in a column will stay; every subsequent one will be removed. (Note: this only works if the rows are ordered so that repeated column values are all grouped together.)

When you’re done, you should have a completely filled-in row, followed by a set of rows that are blank except for the wikipagetext column, followed by another completely filled-in row for another book – and so on. Now for the magic: click the arrow to the left of the wikipagetext header and choose Edit cells > Join multi-valued cells. A window will pop up where you can select the separator; replace the default comma with a space. This will get you the output you’re looking for: a single row per book, with the full text from the wiki page in the final cell.

What we’re ultimately going to want to do is add columns to the wiki spreadsheet that we just cleaned up, for information from the data that Lee gathered from the national libraries. But before we combine the national library data with the wiki data, we need to clean up the national library data.

Step 2. Clean up Quebec data#

What Lee sent me from Quebec was a series of CSVs, one per year (1990-1996). There’s lots of ways you can combine those files, the most obvious– if rather inefficient– method being copying and pasting the content (minus the headers) from all the files into a single file. However you choose to do it, load the resulting CSV file into OpenRefine as a new project. If the default settings don’t pick up the use of a semicolon as the separator, you’ll need to manually configure that under “Columns are separated by” by choosing “Custom separator” and putting in a semicolon. You’ll also need to uncheck “Parse next 1 line(s) as column headers”. Then click “Create project”, in the upper right of the interface.

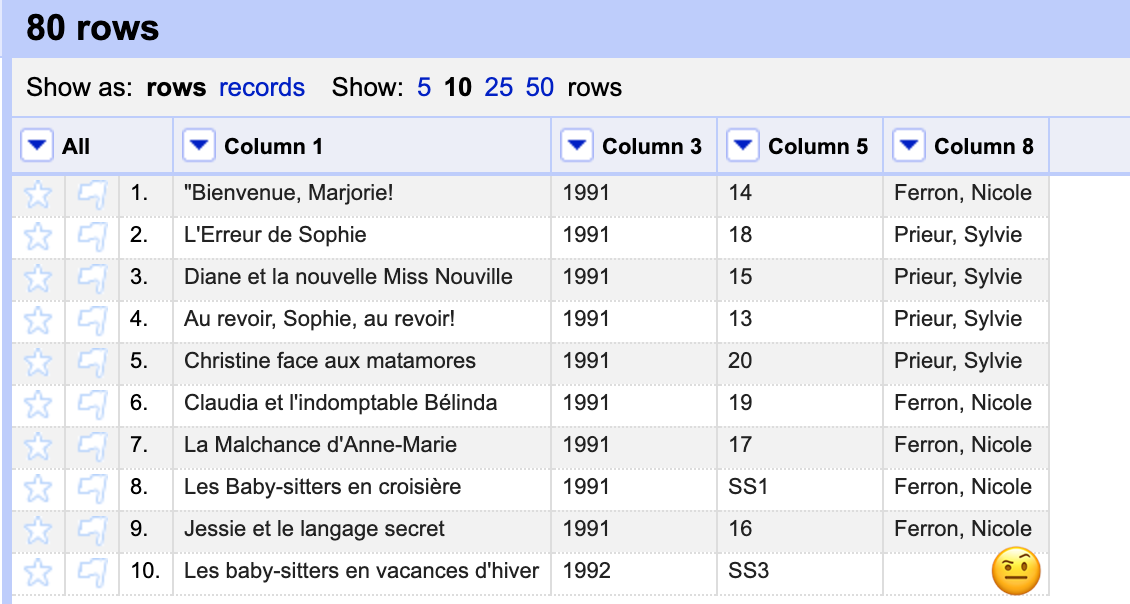

The first record (“Bienvenue, Marjorie!”, if you’re using the data file in our GitHub repo) will be a little messed up – split between two rows. The fastest way to fix this is to copy and paste the values into the right places, then delete the erroneous second row. If you hover over a cell, a blue “edit” button appears in the upper right of that cell, and you can use that to both copy and paste text.

Keeping an eye on the end goal of being able to sync up this spreadsheet with the wiki data, we need one column that has the unique ID for each book. In this case, it’s column 5, which looks like “Les baby-sitters ; 15”; what we need to do is replace the first part with nothing, leaving us just the number. Hit the arrow in the header for that column, then choose Edit cells > Replace and replace “Les baby-sitters ; “ with nothing.

We also need to remove all the “Baby Sitter’s Little Sister” books; click the arrow in the header for the same column that previously had “Les baby-sitters”, choose Text filter, and put in “Le Petit monde de Karen”; this gave me 6 rows, and I deleted them by hitting the arrow to the left of “All” (the column header furthest to the left), and choosing Edit rows > Remove matching rows. This will give you a blank screen of results; delete the text filter in the left column by hitting the X, and you’ll be back to the remaining rows.

Next, we need to normalize the series number for Super Specials, Mysteries, and Portrait books. Hit the arrow to the left of the column that previously had “Les baby-sitters”, and choose Facet > Text facet. This will open a new facet on the left with every unique value in that field. Using that, we can see that all the Super-Special books start with “Les baby-sitters. Super spécial ; no “ and all the Mysteries start with “Les baby-sitters. Mystère ; no “. We can do the same thing – Edit cells > Replace – and replace the text associated with Super-Specials with “SS” and the Mystery text with “M”. (You’ll have to do this twice for the Super-Specials, because the data isn’t completely consistent. All but one use “Les baby-sitters. Super spécial ; no “ and one omits the “no”.) There’s one “Les baby-sitters. Collection Portrait”; just manually change it to “P2” (Claudia’s book was the second one published). If you hover over the text in the facet, you’ll see an “edit” option pop up, and you can edit the text directly from the facets.

Let’s revisit the list of things we want out of this data:

The translated title of the book: we have this in column 1, before the /

A unique identifier to connect back to the original book (book number, title, etc.): we have this now in column 5 after doing the clean-up

Which translation series is it in (e.g. for French: Quebec, Belgian, or France): we know this because of the source of the data

The date it was published: this is in column 3, but we need to extract it from the other data there

The translator: we have this in column 8, but we should clean it up

To get the data we want for the translated title, use the Edit Cells > Replace function for column 1, and check the “Regular expression” box. In the first box, put: (.*) \/ (.*) and in the second, $1. This looks for all characters (letters, numbers, etc.) before a slash, and all the characters after a slash, and replaces all the text with just the characters before the slash. (Yeah, I had to double-check that with a regular expression tester before I used it.)

For the publication date, we need to do the same thing in column 3, but with (.*)([0-9]{4})(.*) in the first box (which looks for the text before the occurrence of 4 numbers, the 4 numbers, and after the 4 numbers), and $2 in the second (which replaces the text with just the numbers, which in this case represents a date.) Don’t forget to check the “Regular expression” box or it won’t work!

For the translator (column 8), use Edit Cells > Replace and replace , trad. with nothing.

Now, we can delete every column except for 1, 3, 5, and 8.

Notice anything? We’ve caught a metadata inconsistency on the part of some librarians in Montreal! The translator column is empty for Les baby-sitters en vacances d’hiver! Is the data missing, or just misplaced? By going back to the original file that Lee downloaded, I was able to find that the info was present in column 1 before we cleaned it up: the person who “adapted it from the American” was Sylvie Prieur. So let’s fill that in manually in the translator column before moving on.

With the data all cleaned up like this, we can go to Facet > Text facet for the translator column to discover that, according to the data we have, there were 4 Quebec translators: Nicole Ferron did the most (24), Marie-Claude Favreau and Sylvie Prieur each did 16, and Lucie Duchesne did 12. If we choose Text filter for the column that has the book numbers, and put in “SS” as the value, we see that no one seemed to specialize in the super-specials, but if we put in “M”, we find that almost half of Lucie Duchesne’s contributions (5 out of 12) were in the mystery sub-series.

Step 3. Clean up the data from the French National Library#

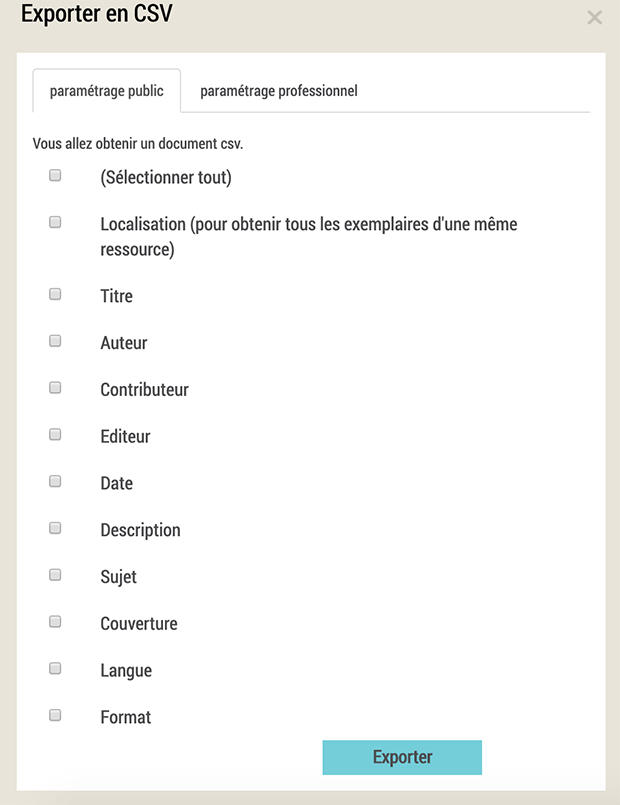

The data Lee exported from the French National Library includes both the books published in France, and the Belgian translations. When you import the French metadata, OpenRefine parses the file correctly by default, and you can go ahead and create the project.

The French metadata includes a record for every copy the library has, so there’s duplicates to eliminate first. Sort the records by the second column, “n° notice BnF”, then in that column, go to Edit cells > Blank down. For that column again, go to Facet > Customized facets > Facet by blank. In the filter on the left, choose “true” (i.e. blank). Then, when you’re viewing only the rows that are blank click the arrow next to “All” and go to Edit rows > Remove matching rows.

To make it simpler to get to see data that we want, let’s delete some unnecessary columns: Type de notice, Type de document, Localisation, Exemplaire n°, Sujet, Couverture, Langue, Format, and the blank final column.

It looks like the Auteur column has the translator information. We could try to get to it by splitting the values in that column (by using Edit column > Split into several columns, using the | character as the separator), but if you start down that road, you’ll discover that sometimes the translator doesn’t get marked in that field, but the translator seems to be more reliably available through the Titre column. Also, the Auteur column doesn’t differentiate contributor role (e.g. translator vs. illustrator), and you’d need to cross-check with the Titre column anyway to identify the correct translator. So let’s work from the Titre column instead.

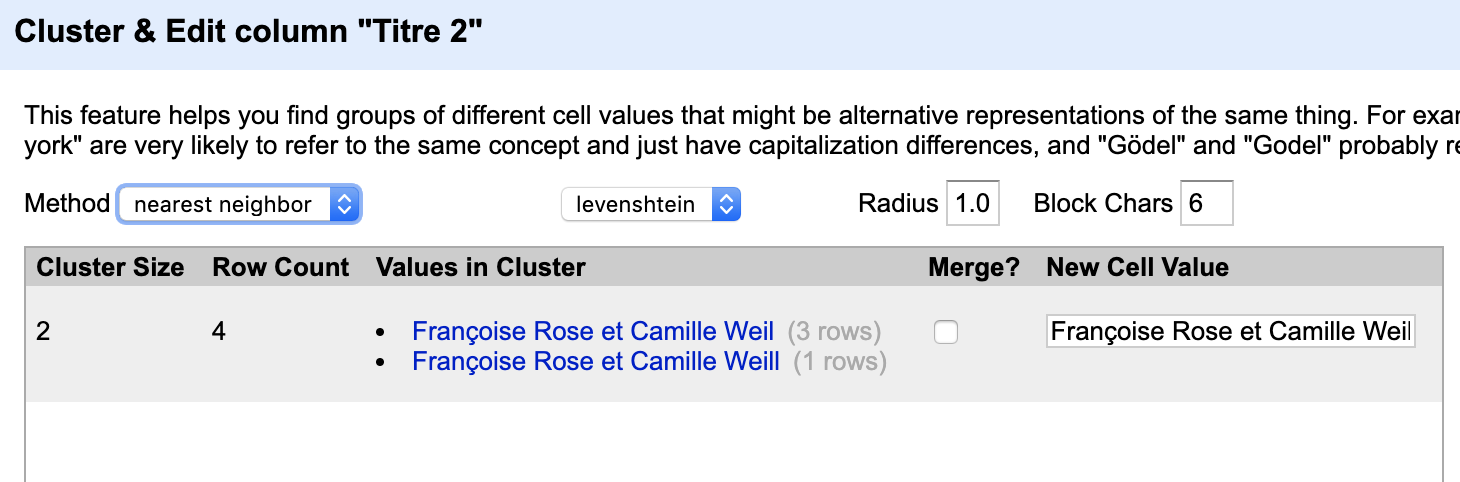

For the Titre column, go to Edit column > Split into several columns using the semicolon as the separator. The resulting “Titre 1” will have the book column and (in most cases) Ann M. Martin. “Titre 2” mostly has translators, with a few illustrators and other kinds of authors (e.g. “a comic strip by Raina Telgemeier”). Only one row in “Titre 3” and two rows in “Titre 4” have a translator. For each of these columns, delete the values that don’t include a translator. The easiest way to do this might be to do Facet > Text facet for each column, and edit the ones that aren’t a translator (by hovering over the value in the sidebar facet, and clicking “edit”, and deleting the value). Once Titre 2-4 are all just translators, go to Titre 2 and go to Edit column > Join columns. Check the boxes for Titre 3 and Titre 4, and choose the semicolon as the separator. Once you’ve merged all values into Titre 2, you can delete Titre 3-4. Next, it’s time to clean up Titre 2, which now has all the translator information. Do Facet > Text facet and use Edit cells > Replace to replace all the variations on “translated by” (e.g. “trad. de l’anglais par”, “trad. de l’américain par”, “traduit de l’anglais (États-Unis) par”) along with extraneous punctuation like “]; ;” until the values in that field coalesce (i.e. until you have more rows sharing the same translator value, without extraneous variation like how “translated by” was written). Another way to reduce variation is by going to Edit cells > Common transforms > Trim leading and trailing whitespace. One other check you can do is go to Edit cells > Cluster and edit. Under the “method” drop-down, choose “nearest neighbor”. This may turn up discrepancies, for instance, like the addition of an extra “l” to Camille Weil’s name in one record:

Check the box for “Merge”, then choose “Merge selected and close”.

How close are we now? Go to Titre 2 and do Facet > Customized facet > Facet by blank.

Oof. 42 books without a translator listed. 11 Belgian books (if you do a text facet on Editeur, the Belgian ones are “Chantecler (Aartselaar)”), 31 France books.

Can we salvage this by looking for the data in other columns? If you add a text filter on the Contributeur column and search for “trad”, there’s 2 rows that have (multiple) translators in the Contributeur column, who didn’t appear in the Titre column, for some of the text compilations (i.e. books that contain multiple original books). Unfortunately, you can’t tell from this how to map the translators to the individual books, so for our purposes, metadata from text compilations is pretty useless.

When I get stuck on one aspect of data cleaning, sometimes it helps to put it down for a bit and work on another part of the file. We know that the file that we’re working with is everything by Ann M. Martin in the French National Library, so there’s non-BSC stuff in here too. The series information seems to be in the Description field, where it exists. Let’s do a Text filter there to search for “La petite soeur des baby-sitters” (the Belgian “Baby-Sitter’s Little Sister”), then remove all matching rows. What we really want is to remove all non-BSC books, and then extract the series number from the Description field. But looking more closely through the data, not all the records have the series number, which is going to make a mess when we try to merge this data with our original English metadata. This is the moment where we realize that this Ghost Cat is also having digestive problems, in addition to its hairballs. We’ve got to lock it in the bathroom before we’re left scrubbing down the whole house.

So what gives? Is the data actually not there? Or is it just not in the download that Lee got?

The Identificat column contains the URL of the catalog record, along with the ISBN number. The ISBN number doesn’t help us any, so let’s go to Edit cells > Replace, check the box for regular expression, and put in .*, which will select everything that occurs after the first space (which appears after the catalog record URL. Replace with nothing. This should get you valid, clickable URLs for each of the entries.

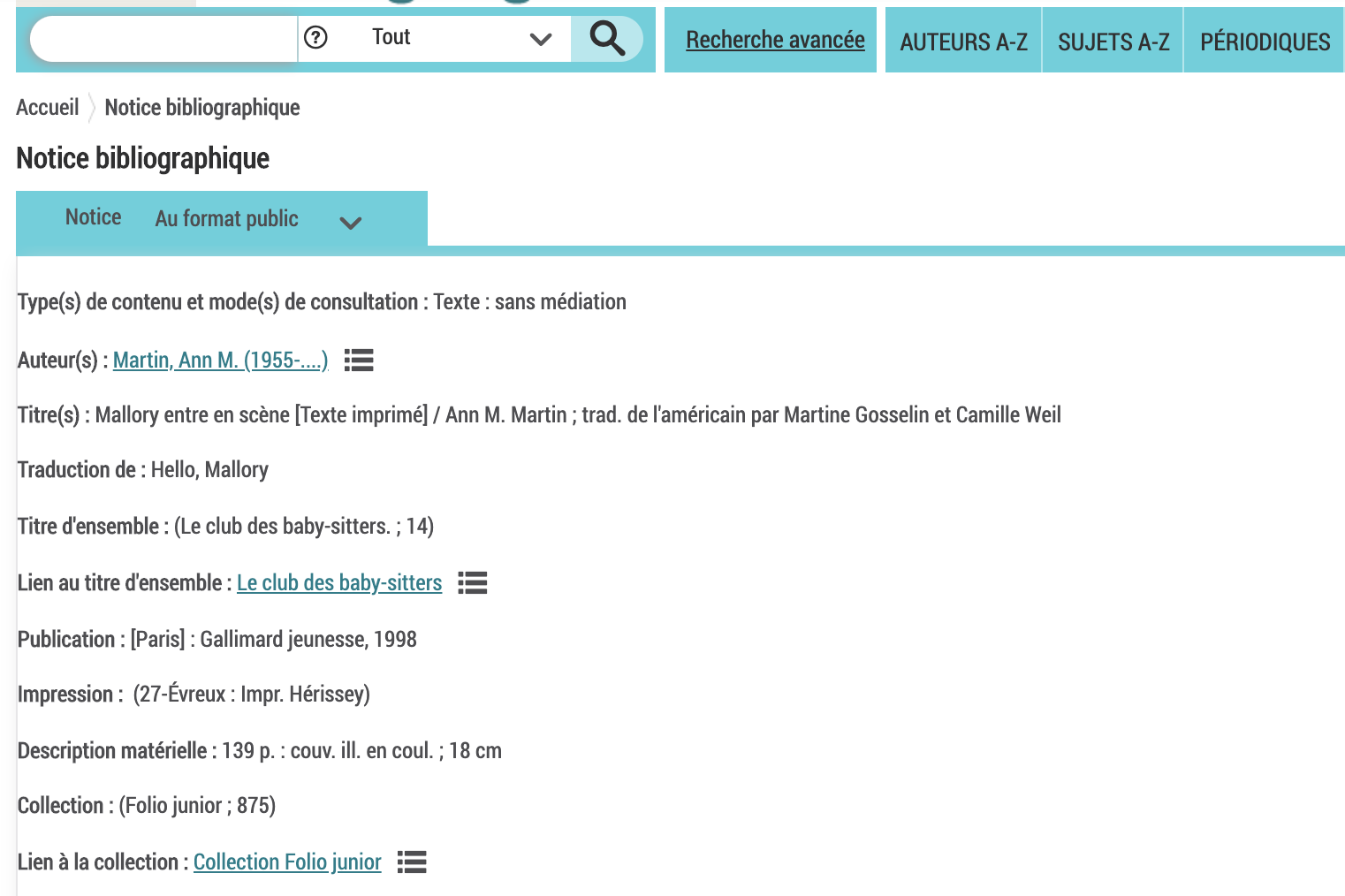

The records where the description starts with “Collection : (Folio junior” are our problem: no series number, and no other way to try to link back to the original English (like the original English title). Let’s check out Mallory entre en scène… and there it is. We’ve got both “Traduction de: Hello, Mallory” and “Titre d’ensemble : (Le club des baby-sitters. ; 14)” in the catalog record.

But if you try to export search results from the catalog, those fields aren’t available.

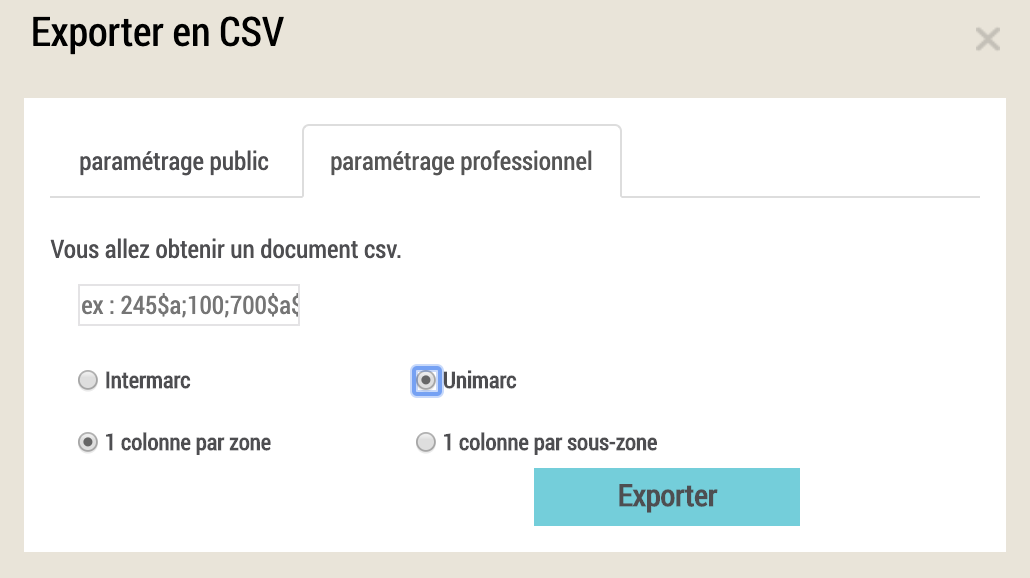

But wait! What about that paramétrage professionnel tab?

Intermarc? Unimarc? I know about the MARC standards for library cataloging, and I have a piece of paper lying around here saying that I’m officially certified as a Library and Information Scientist, but … ugh.

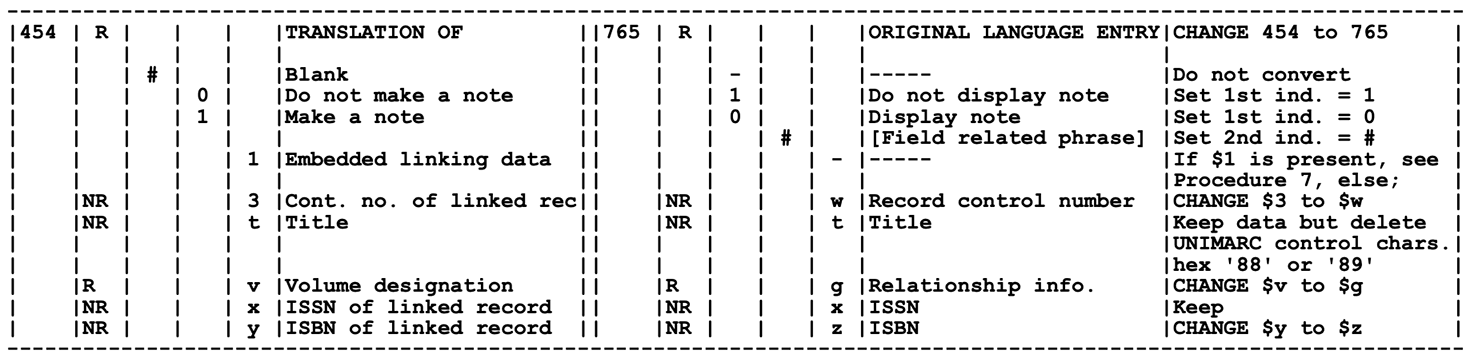

But then I thought about Arcadia Falcone, the metadata librarian at work and one of the most quirky-cool people I know. She’d probably know the MARC codes I needed for these records off the top of her head, and could figure out Unimarc with both hands busy crocheting an amazing shawl. I could do this, too. And thanks to the Library of Congress, it wasn’t actually too bad; there’s a “UNIMARC to MARC 21 Conversion Specifications” that was published only 9 months after the last Baby-Sitters Club book. The formatting alone suggests a promising treatment for insomnia– try it the next time nightmares wake you up in the middle of the night! (I can’t be the only one with that problem these days…)

Searching for “translation” scored me 453 for the field with the English title of the book, and searching for “series” got me 225 for the field with the book number (even better than the English book title). I stuck “225;” into the field, hit Exporter, and held my breath.

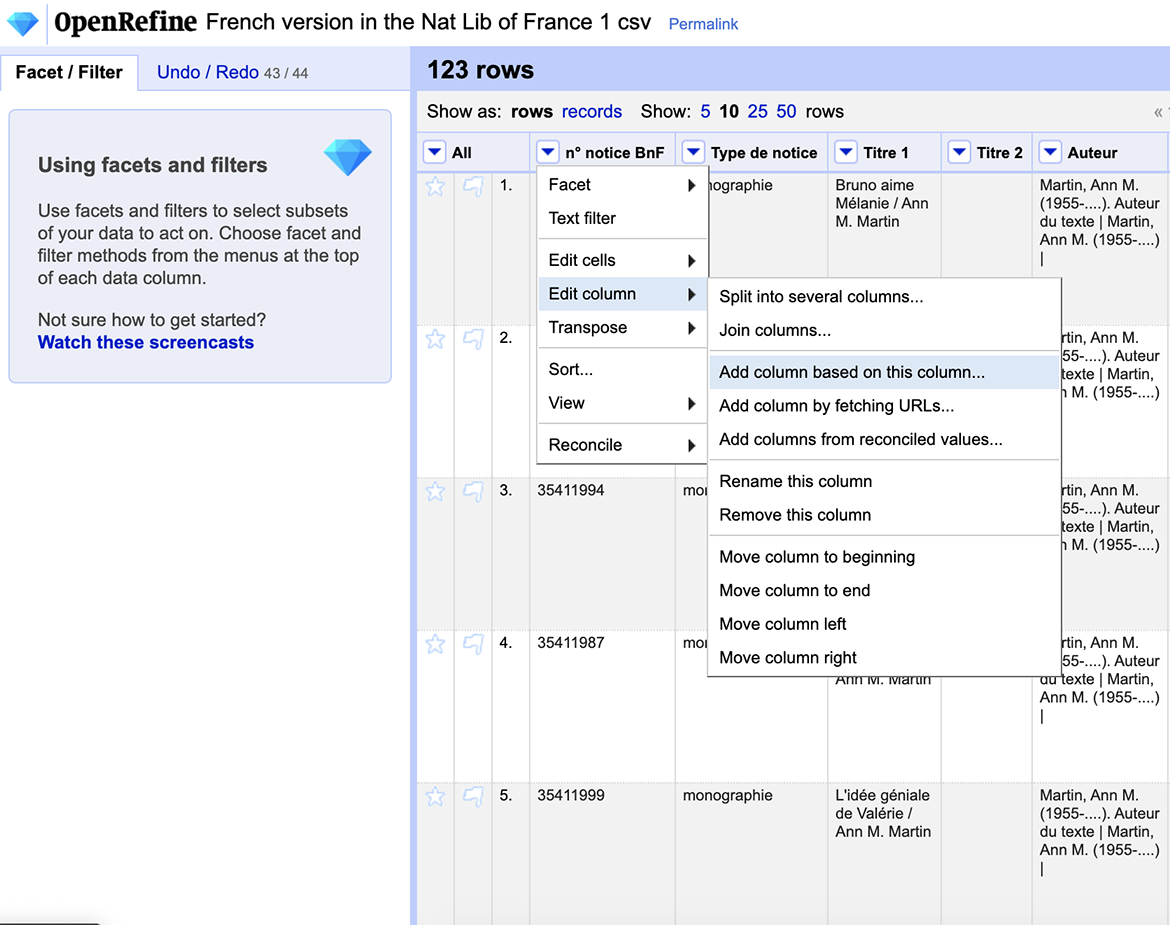

What I got was an ExportPro.csv file, with the fields “Identifiant ARK”, “N° notice BnF”, “Type de notice”, “Type de document;=”225””. The spreadsheet I’d already partly cleaned in OpenRefine had that “N° notice BnF” field, too, as a unique value for each book – all I needed to do was connect my new data with my old OpenRefine project using that “N° notice BnF” value to match everything up. Time for another metadata librarian to the rescue! Ruth Kitchin Tillman recently did an online OpenRefine workshop on “cell cross”, which is the OpenRefine jargon for doing exactly what we need to do here. It’s worth watching for a more detailed explanation, but uses a library cataloging example that might not be as relevant to Data-Sitters Club readers, so let’s run through it here.

Look both ways before crossing the cells#

The first step is to create a new OpenRefine project with our ExportPro.csv that has the series numbers. If you still have the earlier OpenRefine project from the French National Library open, you can open up a new OpenRefine tab by right-clicking on the logo in the upper left, and choosing “Open link in new tab”. Import the ExportPro.csv file, and call the new project “ExportPro”; the defaults are mostly fine, but uncheck the “Use character “ to enclose cells containing column separators” option. The column that we want to import has a name that might cause some errors (it includes quotation marks, which are often a problem in file and column naming). Rename the last column “value225”.

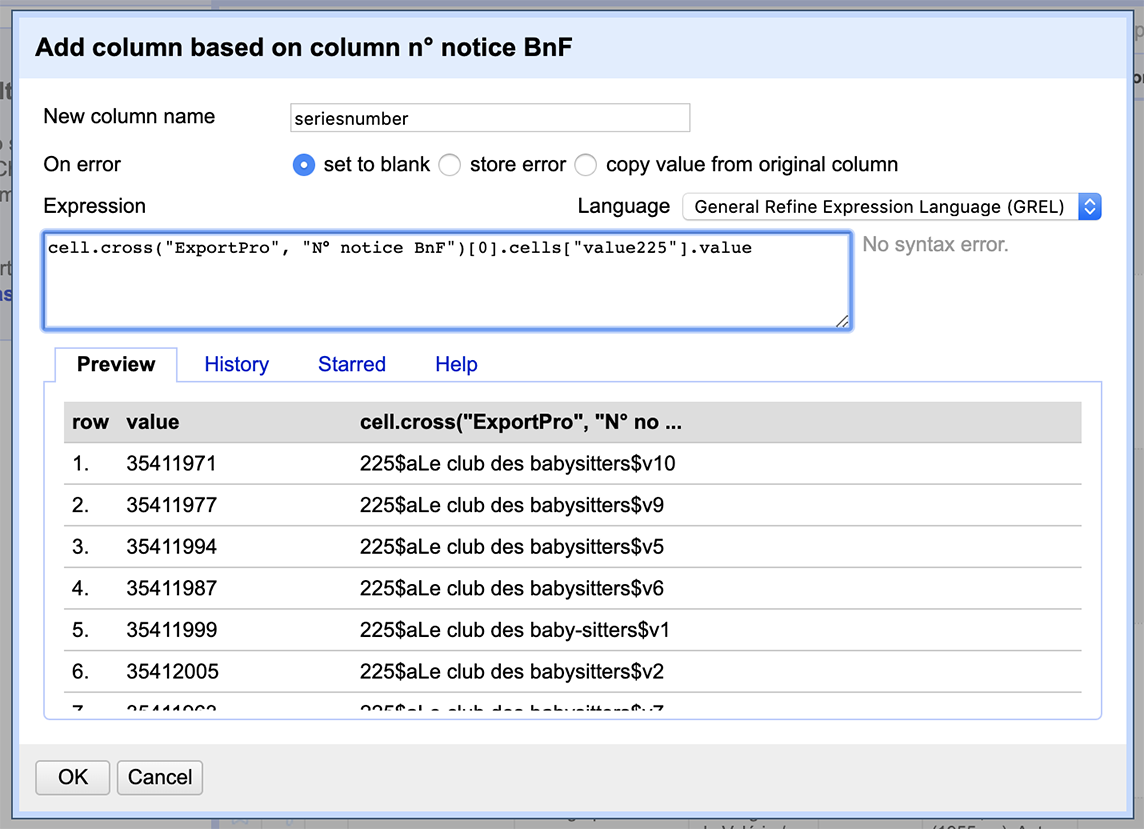

Now, go back to the earlier project with the French National Library data. Go to the “N° notice BnF” column and choose Edit column > Add column based on this column.

In the box that pops up, we’ll call the new column “seriesnumber”. The syntax here is a little tricky, but roughly follows the format cell.cross(“Other-Project”, “Column-to-Match-in-Other-Project”])[0].cells[Column-to-Import-from-Other-Project].value. So in this case, the other project (the one we just created from ExportPro.csv) is called ExportPro, the column there that we want to match against is “N° notice BnF”, and the column we’re trying to import is called “value225”: cell.cross("ExportPro", "N° notice BnF")[0].cells["value225"].value.

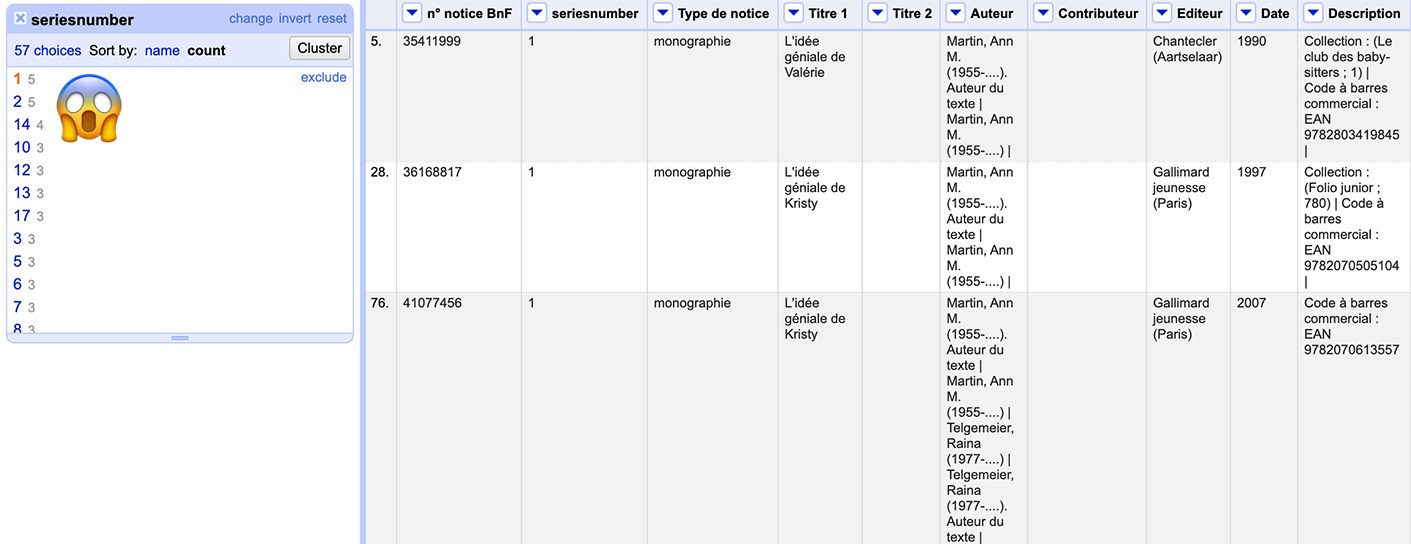

Success! Once you’ve finished the cell cross, you can close the ExportPro OpenRefine project. All we need to do now is clean up the “seriesnumber” field. It’s easiest to start by doing Facet > Text facet on the “seriesnumber” field, to get a sense of how much progress you’re making in your cleaning. Replace 225$aLe club des baby-sitters.\$v, 225$aLe club des baby-sitters.\$v, 225\$aLe club des babysitters$v, and | 225\$aFolio junior\$v(.*) (the broader “Folio junior” publication series) with nothing.

There are 18 records that just have the series “225$aLe club des baby-sitters”; these are the text collections (“Nos dossiers top-secret”, “Nos plus belles histoires de coeur”, etc.) that have multiple books in one. Because we can’t disambiguate who translated which of the sub-books, these records aren’t very helpful for us; you can delete them all by choosing the facet “225$aLe club des baby-sitters”, then going to the All column and choosing Remove matching rows. Do the same for the records with the “225$aFolio junior” facet, which seem to represent series (like the mysteries, or comic books). You can also delete the record in the “225$aFolio junior$v950” facet (not a BSC book), and the records with blank values for “seriesnumber” (more series records or not BSC books). This leaves us with a set of mystery entries. Replace 225\$aLe club des baby sitters mystère.\$v and 225\$aLe club des babysitters\$iMystère\$v with M.

Can we pause for a second and reflect on what it means to have to replace two different values for the mystery books, or three for the main series? Yeah, it’s more work, and that’s kinda annoying, but when I see things like that, it’s a reminder that these records were created by people (and more likely than not, women). It’s easy to treat a giant national library catalog with export functionality and millions upon millions of records as something digital, computerized, consistent – but those records were originally created by people. People who might still be walking around in the world (or, at this present moment, hopefully sheltering-in-place at home). Who are they? What are their lives like? Do they have family members who are sick? Are they in a hospital, with a complex constellation of factors determining whether they’ll be one of the lucky ones who gets a ventilator? Think about that, next time you’re using an online catalog to access digital resources. Real people made these records. And other real people did real work to convert them into the form that you’re using. Pause for a moment to think of those people. And maybe send a thank-you note or cupcakes or flowers or something to your local library’s technical services staff from time to time, once this is over.

A little more tidying#

Let’s finish cleaning up these BNF records and get ready to import them back into our master metadata spreadsheet. We just want the translated book titles in the “Titre 1” column, not Ann M. Martin’s name, so replace / Ann M. Martin with nothing.

We also need to make sure there’s only one instance of each “seriesnumber” value, otherwise the cell cross won’t work. Go to Facet > Text facet for “series number”, and sort by “count” at the top of the facet list.

Uh-oh. We have up to 5 instances of some of these series numbers. Let’s dig into it.

It’s not shocking to get two copies: we have both Belgian and French data here. (We’ll need to export the Belgian data and set it up as its own project for a cell cross, but no big deal.)

What to do about the French data? Clicking through some examples, it looks like it’s coming down to the question of reprints. Now, a book history of the Baby-Sitters Club in French would be fascinating! But remember what I said… um… some 20 pages ago at this point? “Sometimes the hardest part of DH is setting aside all the things you could do, to finish the thing that you’re actually doing.” When I listed “publication date” as one of the things I wanted to get… well, given the choice of multiple dates, I want the first one. Reprints? You all gotta go.

I clicked through the facets; they’re already sorted in a way that works out to be chronological. Because the France-French versions were published after the Belgian ones (which didn’t have reprints), we can go to the “Editeur” column and choose *Edit cells > Blank down**. This removes the “Editeur” field for everything except the Belgian version and the first French version. Do this for each “seriesnumber” facet (e.g. first click on 1, then on 2) with more than 2 values. (“But Quinn,” you might object. “Isn’t that rote work? Aren’t you letting the Ghost Cat win? Couldn’t you script that?” To which I would reply, “Look, it’s fewer than 20 facets, I’m tired, let’s just go clicky-clicky and be done with it, all right?”) As you’re doing it, though, pay attention to the book titles: if there’s anything that looks radically different than the other translated titles, Google it to make sure that the series number is right. Notably, “La revanche de Carla” appears along with variations on “Bienvenue, Marjorie!”; it should be book 15, not 14. It’s also worth going a step further and checking that the facets with 2 values have them from different publishers; for instance, the BNF catalog has two records from France for book #4 “Pas de panique, Mary Anne”, and no record for the Belgian equivalent “Mélanie garde la tête froide”.

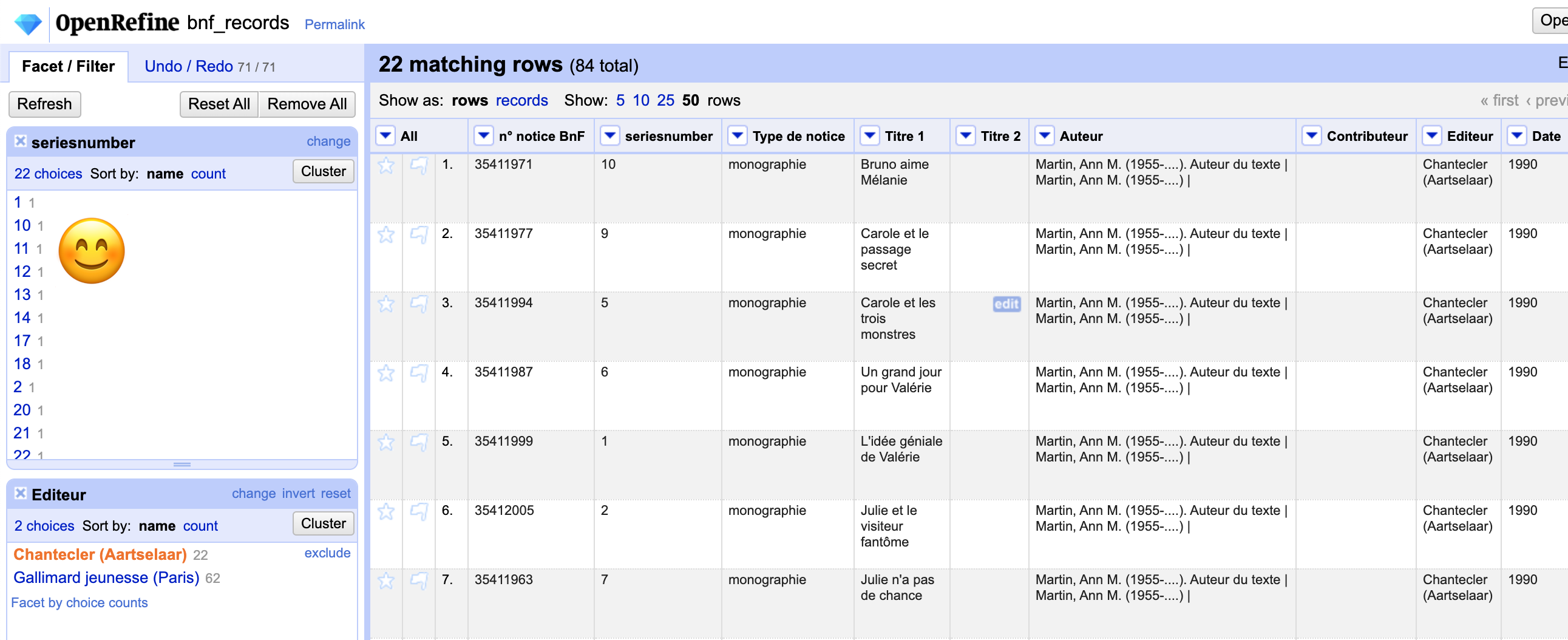

Now, close the “seriesnumber” facet and go to *Facet > Text facet** for the “Editeur” column. Click the “(blank)” facet, and under All, choose *Edit rows > Remove matching rows*. If you want to double-check your work, if you click either the “Chantecler (Aartselaar)” or the “Gallimard jeunesse (Paris)” facet, and add the “seriesnumber” facet, each “seriesnumber” facet should only appear with 1 value.

Close the “seriesnumber” facet, but keep the “Editeur” facet open, and select “Chantecler (Aartselaar)”. In the upper right corner of the OpenRefine interface, go to Export > Comma-separated value. This will give you a new CSV file with just the Belgian records; you may want to rename it bnf_records_belgian.csv just to keep things clear. With that data exported, you can delete the Belgian records from your current OpenRefine project by going to All > Edit rows > Remove matching rows.

Once again, create a new OpenRefine project, this time for the Belgian records you just exported. Import the CSV file you just exported (bnf_records_belgian.csv, if you renamed it). You shouldn’t have to do any additional cleaning on it – it should just be ready to go.

Step 4. Revisiting the fan wiki data#

Before we combine the fan wiki data with the records from the national libraries, we need to do a little more cleanup. Go to Facet > Text facet for the “booknumber” column. There shouldn’t be more than one value for each of the facets, but some of them have multiple values (e.g. “Kristy’s Great Idea” – the very first book – and “Baby-sitters on Board!” – the first Super Special book, both are listed under 1.) If you add a text facet for the “bookseries” column, you can do some bulk editing. For instance, if you select the “The Baby-Sitters Club Mystery” facet under “bookseries”, you can do Edit cells > Replace and replace ^ with M (make sure you check the “regular expressions” checkbox) to put an M at the beginning of all the mystery books. Super-special books should similarly be prefixed with “SS”, Reader’s Request should be “RR”, Super Mysteries are “SM”, Portrait Collection are “PC”, Friends Forever are “FF”, and California Diaries are “CD”. (We just made up these conventions, but they are how we actually name the files in our corpus.)

Once no facet other than “null” has more than one value, you’re ready to bring in the data from the national libraries.

Step 5. The Ultimate Cell-Cross of Ultimate Destiny[1]#

We’ve got four OpenRefine projects open now:

Bsc_book_metadata: data scraped from the fan wiki

Quebec_records: metadata for books published in Quebec

Bnf_records: metadata for books published in France

Bnf_records_belgian: metadata for books published in Belgium

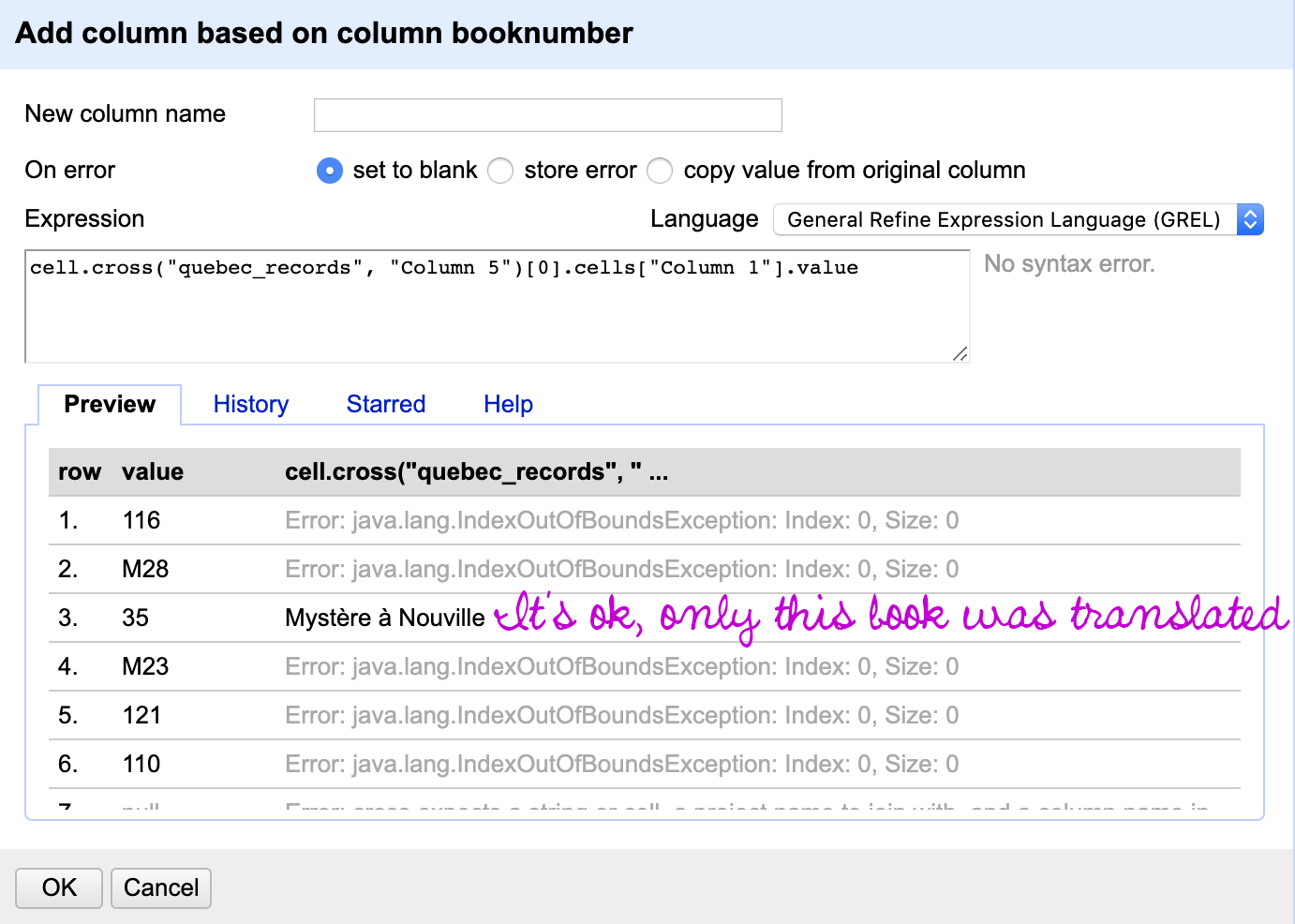

In Bscbook_metadata, go to the “booknumber” column and choose _Edit column > Add column based on this column. You’ll need to do this once for each of the rows in the following table, which spells out what the new column should be called (which should be a good indicator of the data that you’re pulling in), and the cell cross formula you need to get it.

You may see a lot of error messages in the previewed results – that’s okay. We have over 200 rows for metadata scraped from the fan wiki, and only 80 rows from Quebec (and fewer still from Belgium and France). To increase the likelihood that you’ll see results, you can re-sort the fan wiki data by the “booknumber” column, since earlier books were more likely to be translated.

New column |

Cell cross formula |

|---|---|

QuebecTitle |

|

QuebecDate |

|

QuebecTranslator |

|

BelgiumTitle |

|

BelgiumDate |

|

BelgiumTranslator |

|

FranceTitle |

|

FranceDate |

|

FranceTranslator |

|

The last thing to do is to reorder the columns in a more sensible arrangement. Click the arrow next to “All”, and choose Edit columns > Re-order/remove. We’ll re-order the columns so all the French fields are at the end.

Where to from here?#

Finally, we had our spreadsheet for English and French! All the books, all the ghostwriters, and many of the translators. The metaphorical Ghost Cat, curled up peacefully in our lap, purring. So much data brimming with possibility for answering new questions – but what should those questions be?

As we were wrapping up writing this book, I asked Lee to take a look at the “Dear Reader” section.

From: Lee Skallerup Bessette

To: Quinn Dombrowski

Subject: Re: Dear Reader draft

Date: 3/28/20 10:45 AM

Yay! SOMETHING TO DO OTHER THAN LISTEN TO MY SON PLAY VIDEO GAMES AND MY DAUGHTER AND HUSBAND ARGUE.

From: Quinn Dombrowski

To: Lee Skallerup Bessette

Subject: Re: Dear Reader draft

Date: 3/28/20 10:46 AM

LOL! What do you want to do next?

From: Lee Skallerup Bessette

To: Quinn Dombrowski

Subject: Re: Dear Reader draft

Date: 3/28/20 11:17 AM

Weren’t we going to move on to the translation/adaptations of the comic books? I mean, we can comic TEI the snot out of them, and maybe this isn’t a mystery, but that sounds like a fun next step, at least on my end. You sent the French version(s) right? And the Quebec and France ones are the same, we think?

How does that sound?

It sounded great. We’ll take a break from these translations for now, and start exploring the new form of The Baby-Sitters Club that young people these days are reading. We’ll be getting into TEI encoding, methods for image comparison, and whatever else we stumble upon on the way. We’ll be back soon with more. Until then, take care of yourself, dear reader, and those around you.

Suggested citation#

Bessette, Lee Skallerup and Quinn Dombrowski. “DSC Multilingual Mystery #3: Quinn and Lee Clean Up Ghost Cat Data-Hairballs”. April 2, 2020. https://doi.org/10.25740/yx951qc9382.