DSC #13: Goodbye, Friends, Goodbye#

May 18, 2022

https://doi.org/10.25740/jq417jv3351

https://doi.org/10.25740/jq417jv3351

Introduction (Roopsi)#

I literally hate this. “How’s DSC 13?” has been the perennial question in my emails and DMs with Quinn. For months, Quinn has gently nudged me to finish this book because we have others in the pipeline and we’d agreed that we wouldn’t put them out before we paused to do the important work of remembering friends and colleagues that we have lost recently.

There has been so much loss. For all of us. I don’t really want to stop and think about it.

While the DSC has been committed to sharing our forays into quantitative textual analysis in an accessible way, what’s really at the heart of the DSC is relationships. We all came to the DSC with various relationships (or not!) with each other. Lee and I go way back to the early days of DH Twitter. I admired Quinn from afar for years before we bonded over a mutual love for Rent (and Baby-Sitters Club books!). For a long time (unbeknownst to her until recently), I have referred to Maria as “my Cecire,” because my bestie and I are each close to one of the brilliant Cecire sisters and regularly argue about whose Cecire is better. While I knew Anouk’s work, I met her through the DSC and have learned so much from both her expertise and her ways of thinking and being. I met Katia through the DSC as well, but we bonded over our knowledge of the corpus—and because the DSC is about relationships, Katia has already connected me to a friend at my new job.

At the heart of digital humanities are people. Every tool, every project, every book, every article, every Twitter account (bots notwithstanding). These are not techno-social abstractions — they’re people and their relationships with each other.

In this book, we honor Stéfan Sinclair, Scott Enderle, and Rebecca Munson, people we have lost in digital humanities and deeply miss.

Stéfan Sinclair#

The Nicest Person in DH, Ever (Lee)#

When we all met to discuss this book, Roopsi lamented that every time she opens this document, she gets stuck, not knowing what to say, or how to even begin. I have that same feeling right now, trying to find the words to talk about Stéfan. All I can think of is his overwhelming generosity, maybe the nicest person in DH, ever.

He co-built and supported (oh how he supported, even at the end), the text analysis tool, Voyant (originally they were going to call it “Voyeur” but thought better of it). It was the intro to DH tool, one that made DH accessible to anyone, to everyone, freely available for you to plug in your text(s) and see what came out.

The building and maintenance of that tool for our community was a supremely generous act. But his generosity extended beyond DH tools and techniques. He was also generous with his time, expertise, and support of whoever asked for it in the DH community. When I was teaching contingently and on the literal and figurative fringes of DH, trying to find a way in, to develop my skills and knowledge, I mused on Twitter about possible summer internships for contingent faculty at DH centers. Stéfan reached out to me immediately and said, if I was interested, I could come and work with him over the summer in Montreal. While it never worked out, me spending the summer at my mom’s with the kids, with her taking the kids to the pool during the day while I worked on DH stuff with Stéfan, just that he offered was a sign of just how generous and supportive he was.

He was also playful, and there was a joy in his work. When Voyant unexpectedly updated WHILE WE WERE TRYING TO TEACH IT, my colleague Zach Whalen and I, with our Digital Studies classes, explored the new, added features of Voyant and were struck by one new visualization: the word knot. WTF was a word knot and what did it tell me about my text? It was mesmerizing to watch it twist and turn and develop, but Zach and I could not make heads nor tails of what we were seeing. When asked what the word knot represented, I could almost hear Stéfan winking through Twitter when he answered, well, what do YOU think it means?

Stéfan also pulled off the monumental task of literally bringing the entire world of DH to Montreal when he was one of the co-organizers of the 2017 International DH Conference. It was a celebration, a party (as all things are in the summer in Montreal), a large feather in Stéfan’s already-full cap. I remember seeing him at one point during the conference, finally having a chance to say hi to him, to praise his work in putting the conference together, to thank him for bringing the conference to Montreal. The first time Stéfan and I met in person was at the Nebraska DH conference, when at the opening reception he spotted me, raced up to me, exclaiming my name, and immediately embraced me in the standard Québécois greeting of giving a quick kiss on each cheek. I didn’t recognize him immediately, and it showed on my face. He rushed off to greet someone else, but almost immediately DM’ed me, “You didn’t know who I was, did you?” and we both laughed about it. This time, he looked tired, which I chalked up to him organizing an international conference.

Little did I know. Little did any of us know.

Few of us knew until the end, until he was gone. The shock of it was overwhelming. I got the news from my podcast co-host, who I didn’t even realize was close to Stéfan, but she was best friends with his wife, having met all those years ago at the University of Alberta. The DH community lost an invaluable builder, but a wife also lost a husband, kids lost a father, students lost a supervisor and mentor, and people lost their best friend. I didn’t know him in those ways, but to hear my friend’s deep-seeded grief over his loss drove home just what kind of all-around good, nay great, person Stéfan was.

He was, shit, he still is, beloved by so many. We learned from and were inspired by his generosity, his playfulness, his spirit. I know he loved the DSC, and I think this whole project is, in part, a reflection of the influence he had on me, on all of us. DH was fun for Stéfan, and that spirit never seemed to have disappeared or dissipated, even after all those years in academia. He wanted to make it accessible, to make it available. I’d like to think that there is a little bit of Stéfan in every single “DH for Fun” project that gets cooked up and unleashed in the world.

At least, there should be.

My DH Pin-up Calendar Star (Roopsi)#

I used to joke that if I had a digital humanities pin-up calendar, Stéfan would appear in all 12 months. This was not objectification of him for being a handsome man (which he was) but because he was one of those people who simply radiated kindness — how could you not want that on your wall from January to December?

Like Lee and many others, I first came to know Stéfan as a creator of Voyant Tools (along with Geoffrey Rockwell). Playing around with Voyant, as a graduate student at the time, I wondered about its creators — who were the people who had an idea for a tool, thought to share it with all of us, and actually found a way to do it? This was not simply about admiration for the tool but for the people behind the tool and their ways of being scholars. While I had no idea how one would actually do that, the tool — and the people behind it — showed me a way of being an academic that was far more expansive than I could have dreamed as that graduate student poking around Voyant. We could take our ideas and find ways to build the tools and the infrastructures that support the research of others’ in our fields. That was the kind of scholar I wanted to be.

The first time I met Stéfan was at Congress in Ottawa in 2015. The Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH) and the Canadian Society of Digital Humanities/La société canadienne des humanités numériques (CSDH/SCHN) were holding their first joint conference. Stéfan was outgoing chair of ACH and the incoming chair of CSDH/SCHN. At the ACH executive meeting held at the conference, we joked about Stéfan leaving the presidency of one organization to take up another. This was another Stéfan-related moment of revelation: leadership and building relationships was another way of building a field and supporting colleagues. That was the kind of scholar I wanted to be.

After a long conference day, I was sitting on a bench somewhere on the University of Ottawa campus, and Stéfan came over and sat down next to me. We had, of course, met through ACH but most of our interactions were mediated from afar through social media. This was the first time we just sat down to chat. I was coming off a tough several years of my early career. I’d made a poor choice of a collaborator because while our values for promoting attention to colonialism in digital humanities aligned, our strategies for doing so did not. Because my collaborator was far better known than I was, a lot of the senior folks in digital humanities assumed that I was party to their actions, which I wasn’t. Many were ready to write me off. Stéfan wasn’t.

We talked seriously about what it meant — and what it would take — to realize a vision of digital humanities that was globally, linguistically, and intellectually expansive, that would be more welcoming and be open to the kinds of critiques for which I and the others with whom I was still working were advocating. Stéfan shared his approach — the one I’d observed through his work and leadership — and offered his advice and insights.

At a difficult time professionally, having the chance to have that conversation with someone I admired and who was so well-respected in the field helped me regroup and to orient my professional identity towards a series of actions that continue to guide my work today. I will forever be grateful to Stéfan for that.

The irony isn’t lost on me that we are publishing this DSC book during the second joint conference of ACH and CSDH/SCHN, which also includes a partnership with Humanistica, the francophone organization that Stéfan was instrumental in founding. And, at the same time, I’m about to become co-President of ACH along with Quinn. I’m grateful to be doing this in the tradition that Stéfan, star of my DH pin-up calendar, set for the field.

Scott Enderle#

Digital Avatars Remain (Quinn)#

If you’ve been following along with the Data-Sitters Club series, you’ve already met Scott Enderle in DSC 8: Text-Comparison-Algorithm-Crazy Quinn. He was the developer of amazing and usable things like the Topic Modeling Tool, and a nifty script for doing fuzzy comparison of 6-word sequences in different texts. Scott sat down with me in April 2020, answered my million questions, and helped me work through the problems I ran into. When I got stuck later, he was just an email away.

A really great thing about the collaborative nature of DH is that it generates all these connections between people. They’re not the closest relationships — I don’t go through my mental rolodex of past project collaborators when I need to celebrate some victory or vent some frustration — but they’re surprisingly durable. Right now, as of March 2022, my life is consumed by emergency web archiving in Ukraine through a project called Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online (SUCHO). We’ve got over 1,300 volunteers who’ve signed up to help — and among them, I’ve seen the names of people I’ve met at DH conferences, workshops, and events. People I’ve chatted with at coffee breaks, maybe grabbed a drink or dinner, gotten into a debate about technology choices. People I hadn’t seen or talked to in years, in some cases — even for years — pre-pandemic. But they saw this emergency effort, and they showed up.

I was going to be that person, popping back into Scott’s life with tales of how I’d used his code in cool ways to do interesting things, and maybe a few more small questions. Because I had more questions for him. I still do. I can think of other projects where I could use that 6-gram comparison code.

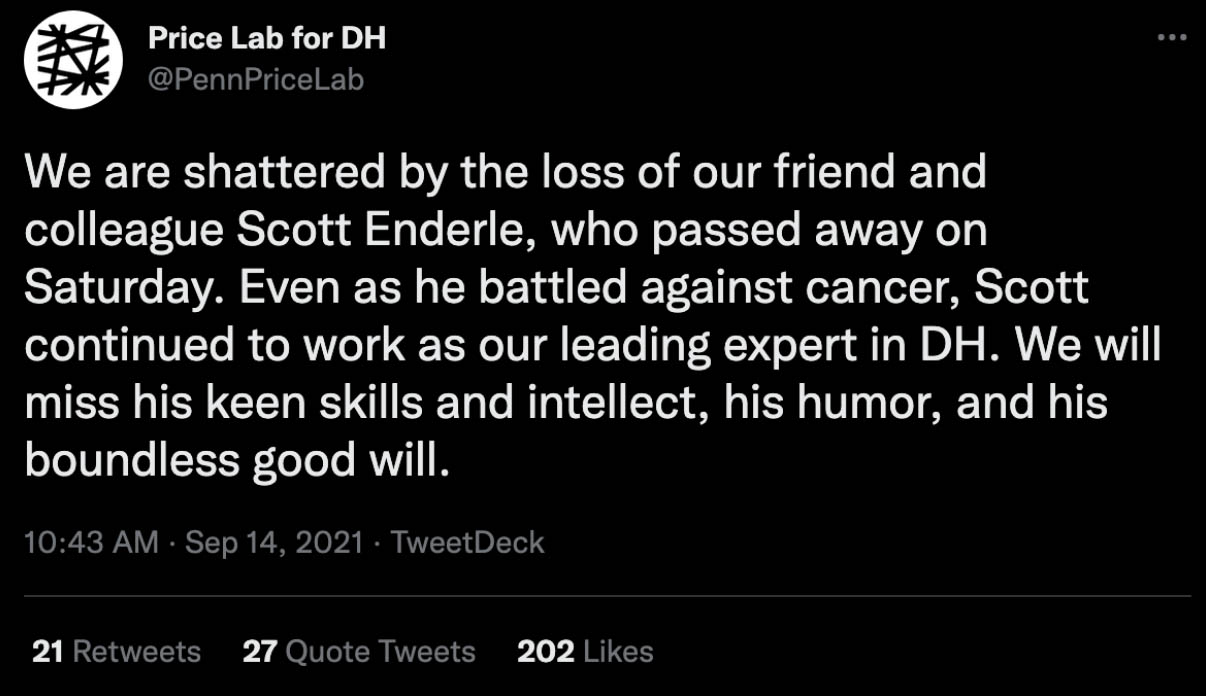

Except I logged onto Twitter on September 14, 2021 and saw this:

I was on some other Zoom call at the time, thankfully on mute, but I remember the word I spoke aloud when I saw what Nikki had just tweeted, alone in my office at work. “OH! …. Oh.”

On that call for DSC 8, Scott mentioned, casually, that he had cancer. But it seemed pretty clear that he’d rather talk code than cancer, and I didn’t want to pry. I asked after his health a few times since, with folks I knew who worked more closely with him, but I’d never heard anything that made me think things were especially bad. And life carried on and I meant to follow up with those questions but every day ended without me getting to the bottom of the to-do list and I pushed it off another day, another week.

There’s always time until there isn’t. There are always ties until they’re severed. But are they severed, really? Ben Schmidt’s blog post tribute to Scott, “Increasingly Stealthy,” is one of the most beautiful tributes I’ve read. And I’ve had that same experience since Scott died — Googling my way into random corners of the internet, only to find him there with a helpful answer. And there’ve been other moments when I’ve felt like Scott was there with me saying, “You’ve got this.” Like the time I got an urgent request to compare French far-right political books, looking for repetitions of similar — but non-identical — phrases. Once again, his code was there to save the day.

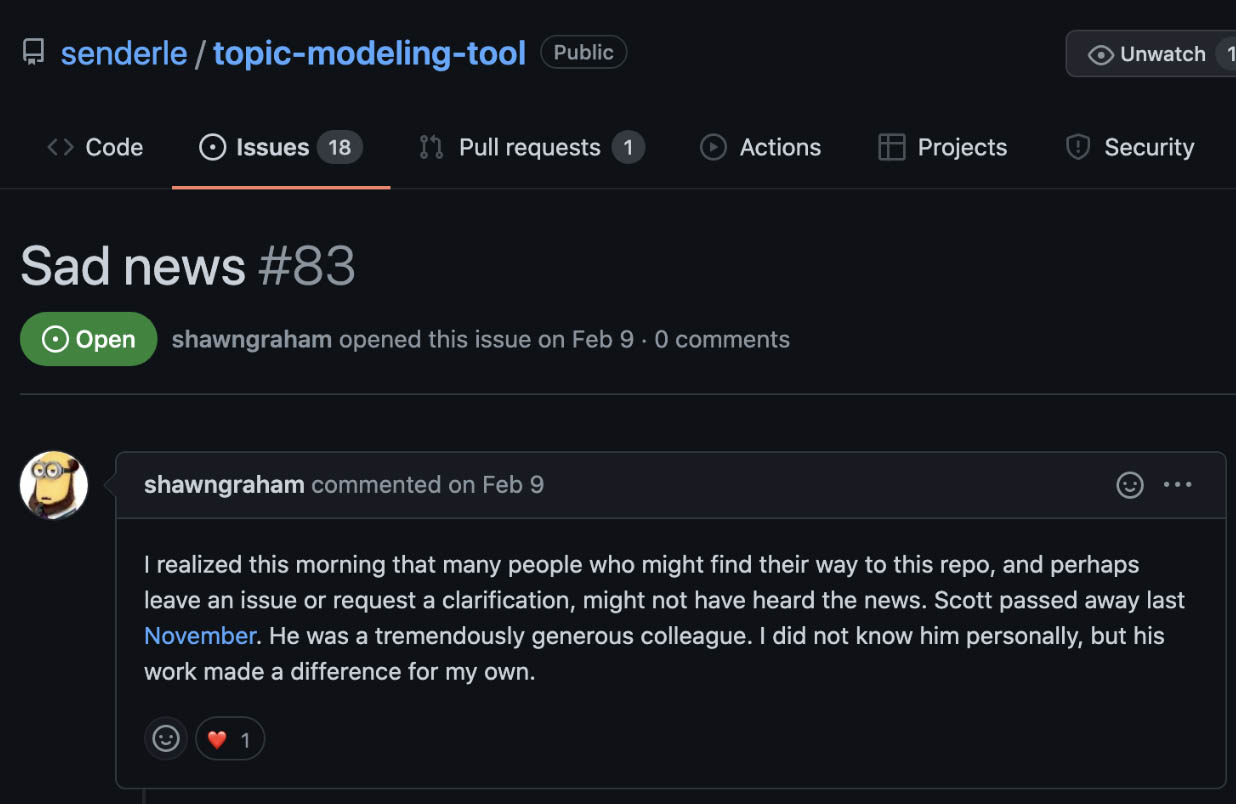

I meant to pop back into Scott’s life; instead, now he pops back into mine virtually. I’d been watching his Topic Modeling Tool repo on GitHub forever, getting emails about all new activity. So sometimes Scott — or at least his digital avatars — appears in my inbox. The first time was a couple months after he died, someone having problems with the download link. The second time was in February this year, when Shawn Graham posted the ultimate bug report.

I miss Scott. But I’m grateful for the ways he was so very online and connected. I know I’ll run into him again — be it in my inbox, or my browser, in the nooks and crannies of the internet. And every time it makes me smile.

If Only He Knew (Roopsi)#

How can someone you met once be so influential for your work? That’s a question I think about when I remember Scott. We met once, never really spoke beyond that, perhaps we corresponded by email a few times, but Scott’s work and mentorship of students played a crucial role in the work I have done in postcolonial digital humanities — and he might never have known.

When I was writing New Digital Worlds, I was trying to articulate the various ways that coloniality permeates the practice of digital humanities — and, in turn, how we might use digital humanities methods to undo it. The one place I was stuck, apropos of our work with the Data-Sitters Club, was quantitative textual analysis. I had the critiques down. That was the easy part. (Astute readers will recognize that I’m a quantitative textual analysis curmudgeon of the DSC.) What I couldn’t figure out was how it could be used in powerful ways to critique colonialism.

Enter Scott Enderle and Mae Capozzi, one of his students.

I had the good fortune to come across their research on “A Distant Reading of Empire,” which applied the ideas that colleagues and I had been articulating at the intersections of postcolonial studies and digital humanities specifically to quantitative textual analysis. For the project, they used MALLETT (Machine Learning for Language Toolkit) to topic model a corpus of 18th century British literature to study how India was represented in the corpus. That’s to say, what can reading 3,000 colonial texts tell us about how the British Empire constructed colonial subjectivity? Among their results, they identified a trend consistent with critiques of colonial discourse in postcolonial theory — representation of colonized people as objects of knowledge not active agents — through their topic modeling work, which revealed that the corpus is more engaged with British colonial investments in India than it is with actual people in India.

Scott and Mae’s work was a final puzzle piece that I needed to finish New Digital Worlds. Their work ensured that my treatment of literary studies in the book wasn’t simply criticism but could also shed light on the powerful interventions that are possible when we combine digital methods with postcolonial theory.

I wish I’d had a chance to tell Scott and to thank him.

Rebecca Munson#

The Power of Purple (Quinn)#

Imagine someone so charismatic that when they ask their large social media following to “pick up the purple” after a breast cancer treatment finally claims their purple-dyed hair, your response is, “Absolutely” … even though you’ve never met them in person.

Imagine if you read something this person wrote in a new journal, touching on a childhood author that you, too, were fond of — much fonder of, in fact, than Ann M. Martin’s Baby-Sitters Club books. And your reaction is to reach out to them via Twitter DMs, and have a long conversation about this author, and mull over a future project: what if we could extract dialog from these books uttered by doctors, those adjudicators of the continuum between life and death? What do doctors look like in these books? What do they sound like? How does that compare to the actual experience of being a cancer patient? And this is how you discover that “imperfect” isn’t close to being the word for computational quote attribution. And it’s impossible, but you can’t bring yourself to face giving up, because this is a collaboration you want to make happen somehow, because your internet friend is into it so you’re into it too.

Imagine seeing the news from this person’s blog that it’s over, the treatments aren’t working, they’re going home to their parents’ house to die. A sunny day out at a baseball game suddenly turns dark. And when the news comes that they have maybe a month left, you light up Slack. What can we do? A month. A month is enough. What about a festschrift? Let’s pull something together so she can see it.

We didn’t have a month. We didn’t have weeks. I didn’t know Rebecca when I did DH the first time (2004-2017); I met her on the internet when I came back to DH in late 2018.

Her last blog, “Pitiless Achilles Wept”, starts with a dump of CareBridge updates in April 2019. Six month after I came back to DH. Not long after I started following her on Twitter. In retrospect, Rebecca was dying the whole time I knew her. Slowly, then quickly at the end.

We cared about some of the same things. Not just 90’s YA dying-girl books (Lurlene McDaniel FTW), but project management and grad students. She came to DH late in her education; I came to it early. She left Berkeley not long after I arrived. We were both at ACH 2019, but never spoke. We were together on a handful of Princeton-based Zoom calls, when it was already near the end, when my hair was purple and so was her scarf and we laughed about it.

Rebecca didn’t do the kind of computational text analysis we explore in the Data-Sitters Club. She managed projects, and people, and helped run a center. That work is harder to quantify, harder to point to and say “this, THIS was Rebecca’s contribution to DH” like we do with Stéfan and Scott. But I have nothing but strong words for anyone who dares to even imply that her contribution was any less for not being code or tools.

If you talk to her colleagues at Princeton, they’ll tell you she was great at what she did. That it made a difference.

If you talk to anyone who considered her a friend, you’ll also quickly see that what she did, as such, in DH wasn’t the point. It wasn’t about what she did — though God knows we could use more people in the field who care so deeply about helping grad students find a good path for themselves. It was about who she was.

I’m not the person to tell that story; there are so many more people, from her grad school colleagues to her in-person friends like Maria, and Matt Lincoln, who were her friends in a way where they can tell that story. What can I add here? Except, perhaps, that as a grizzled aging DH person, I can say with some perspective on the matter that Rebecca was special. Her unflinching honesty and forthrightness, her devotion to work she saw as meaningful, her whimsy, her refusal to cede cancer any more ground than she absolutely had to. Your eyebrows fall out due to treatment? If you’re Rebecca, you go get them tattooed right back on and post selfies about how awesome they came out (and, really, they did.)

Before I knew how close the end was, when I thought maybe it’d be okay, that a treatment would work for her, that Rebecca would make it, I planned to dye my hair back to brown when I started going back to campus regularly. My colorful dresses were one thing to wear to Stanford; blue and purple hair felt like a level of provocation beyond what I dared. Maybe it was safe via Zoom, but walking through those Spanish-style arcades felt like another thing altogether. Those plans went out the window when Rebecca died. I had just re-dyed my hair, making it particularly day-glo blue in back and purple in front, one afternoon when I was having lunch with a friend at a spot near campus. It was the day I heard that Scott had died. Out of nowhere, unprovoked, an old woman walked up to me, gestured towards my hair, and said, “Does THAT wash out?” In my fresh grief and general disorientation around being back on campus, I was befuddled for a moment. And then I answered, “I hope not.”

This is What a Feminist Looks Like (Maria)#

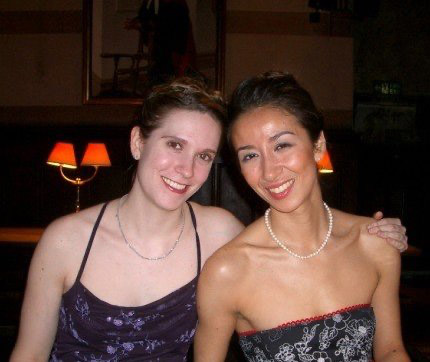

In my first year of grad school, a group of us ordered t-shirts with the phrase “this is what a feminist looks like” emblazoned across the front of them. Rebecca may have even organized the order; I can’t remember now. We were an interdisciplinary bunch of women, brought together by the college system at the University of Oxford. Unlike the undergrads, whose educations take place primarily within one of Oxford’s 40+ colleges and halls, our college affiliation was mostly a housing and social affair; graduate coursework and research is handled at the university department level. But since we lived together, often ate together, and went out together, we quickly developed friendships — our fields of study were incidental, though we loved getting each other to hold forth on our nerddoms of choice. Early modern literature (Rebecca). Medievalisms in children’s culture (me). Comparative theology. Physical geography. Archeological science. Neuroscience. Psychology. Law. Animal sex habits (everyone’s favorite, really). Rebecca and I were friends in this context: not best friends, but friends, part of a group. She lived in the room above mine; we talked shit and Shakespeare and borrowed each other’s clothes, we dissected dates and raged against inequality and hung out in our pajamas.

Our Victorian red-brick college, Keble, sat close to many of Oxford’s main science buildings at the time and so the graduate community was full of scientists — including several of us, see above. And men. In our incoming year, we estimated that the ratio of men to women at Keble was something around 5:1. I won’t hazard a guess at the racial breakdown but suffice to say it was, like the university in general, a Predominantly White Situation. We were friends with many of those men, laughed with them and made memories with them, and some of those guys remain among my dearest friends today. We had a LOT of fun. But in that first year, suddenly surrounded by deep leather couches and dreaming spires and a startling number of official events that involved port and formal attire, having a group of smart feminist women friends turned out to be essential.

Frankly, a lot of stuff was fucked up. It was the little things, like being called “scary” or jokingly told to “go iron something” when we called people out for sexist and homophobic language or behavior. The bigger things, like being violently cursed out and called lesbians (as if it were a slur) for not accepting drinks from men at bars, or the months-long campaign to take away the £3 cookie budget for our weekly “Ladies’ Tea” because a group of male peers didn’t like communal funds going to a women-only space. The crushing, impossible things, like the stories we traded (often at those tea breaks) of professors and advisers who sexually harassed and assaulted women students, but who continued in their positions unchecked even when administrators were well-aware of the patterns. Who to avoid, who it was safe to talk to, what to do in case.

Rebecca went as hard for the feminism as she did for the fun, and was as likely to sport her “this is what a feminist looks like” t-shirt around Oxford as a sexy pirate costume at one of the seemingly innumerable “fancy dress” parties. She was frank, proud, and unapologetic of who she was in a way that I found impressive then and I still find impressive today. I was quick to verbally tangle with a peer and up to challenge a professor or institutional leader when I felt it important in context, but my upbringing and personality made me shy to walk around wearing a slogan that could invite controversy. I think my feminist t-shirt mostly made appearances at bedtime and the gym; not Rebecca, who sported hers for years. Maybe she already understood how an unrepentant slogan can be a solidarity-forming “Fuck that!”; and that it takes a critical mass of that kind of discontent to make inequitable norms stop seeming so normal.

She wasn’t superhuman; in fact she was intensely, vibrantly human, with as many insecurities, fears, and flaws as the rest of us. She was as likely to be giddy in love, high on her achievements, crushed with disappointment, or flattened with exhaustion as anyone, and maybe her openness made her seem even more so. But Rebecca was self-esteeming: she esteemed herself, rightly believed that she deserved good things, and was happy to accept praise where it was given. She moved back to the US for her PhD after completing her MA that year and I continued on at Oxford; we stayed in touch in the sporadic, mostly-digital way that many of us do after distance puts us on divergent life paths from our friends. Since we both did our degrees in English we saw each other a couple times at MLA, but it wasn’t until we both ended up doing DH-related work that we started to see each other more often again.

She landed at the Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton (CDH), and her colleagues there have written movingly about all that she brought to that center and community. Rebecca was profoundly scholarly and truly believed in work, as one of our close Oxford friends reminded me after reading a draft of this piece.* Even when she was drained for personal, professional, or health-related reasons, she was tireless in her intellectual efforts. Unsurprisingly, her sense of justice infused that work, and she was part of the larger shift in the field towards a critical, self-reflective digital humanities that embraces feminism and rethinks its methods, approaches to data, and outputs according to more inclusive visions of what the humanities can and should be. I had founded the Center for Experimental Humanities at Bard, and we vibed about the wide world of potential that feminist, anti-colonial perspectives and histories could bring to humanities projects. I remember her showing me a CDH textile project that I absolutely fell all over at ACH2019 in Pittsburgh — and the next semester I found a way to integrate a weaving data assignment into a Woman as Cyborg course I taught for EH.

In spring of 2021 one of our Keble friends, a Brit (the one who studied animal sex habits, she still kicks ass) posted on Twitter that the UK’s Vagina Museum had “Fuck the Patriarchy” jewelry for sale. I clicked, I looked, I was in love. I immediately thought of Rebecca, who still turned up in social media posts in her “this is what a feminist looks like” t-shirt years after I’d forgotten what even happened to mine. I ordered two necklaces, one for me and one for her. They took a while to arrive, and then life happened — hers sat in a pink box on my dresser for months, and between the fact that the continuing pandemic had sharply curtailed my going-out opportunities and the fact that my second child was a very grabby 10-12 months old at the time, I barely wore mine, either. Life is change, is churn, is motion: New York started to open up, and I moved my partner and kids from the Hudson Valley to NYC for a job I’d started virtually. Before one of our last big carloads to the city, I finally cleared my dresser and messaged Rebecca to ask for her address. She gave it to me but told me she’d soon be at her parents’ for a while, so sent me that address too. I grabbed a vintage postcard of a classic Barbie and scrawled something on the back about icons of femininity and how the necklace had reminded me of her, sent my love, and put it with the pink box in a padded envelope that I mailed to her parents’ address just before we drove out of town.

Three weeks later, one of her friends posted that she’d died. I don’t know whether or not Rebecca saw the necklace, but I hope that she did and it made her smile. After she passed, the Keble women gathered on a group chat — the first time we’d all convened in that way — and then on Zoom, and cried together. Some of us hadn’t spoken to her in years; some were in touch irregularly, like me; one was a best friend to her through it all. We pooled our money and made a donation to her breast cancer charity of choice — we thought about leaving something to Keble in her name (an endowed cookie fund for graduate Womxn’s Tea came under discussion) but we ultimately agreed that Rebecca knew what she wanted and was not shy about saying it. So METAvivor (Metastatic Breast Cancer Research, Support, and Awareness) it was.

With her purple hair and passion for justice — justice for all people but also, crucially, including herself — Rebecca was one beautiful, much-loved example of what a feminist looks like. I think of her whenever I wear my “fuck the patriarchy” necklace; I still get shy, especially since I’m pushing 40 and most likely to be wearing it to a playground on a weekend these days (Hi, other parents! Hi kids!). But I try to remember how proudly Rebecca displayed her beliefs, and to esteem my own values enough to wear them shining around my neck. And I recall that a middle finger to a system that oppresses people of all genders is both a shout of solidarity to whomever may need to see it that day and a statement of my own worth, and that I deserve that, too.

Rebecca was a digital humanist, but we are all so much more than the jobs we do, even as all we are inflects our work and vice versa. The outpouring of grief from the DH community at her death was a reflection of how widely her intellect and spirit were felt, both by people who knew her well and by those who encountered her primarily through her work. She and I were friends, and I am deeply grateful for the time we spent together. The things I learned and the people she touched aren’t some silver lining to her loss, though. It’s not alright that she died so young; that shit is fucked up. Sometimes it’s good, and right, to say so. And it can be in those states of shared outrage that we find our people and connect with our best selves.

* Special thanks to Anbara Khalidi, a best friend to us both, for reading and offering feedback on this piece. Anbara is pictured in the third photo, above, taken in the early years of our friendship.

Conclusion (Quinn)#

And that’s it. Whether or not you ever met Stéfan, Scott, or Rebecca yourself, what we hope is that you remember them. The stories we’ve shared here, and the stories you may hear from others. We have lost too many people recently. And while I’m usually the one to roll their eyes and insist that “DH is such a new field” is too frequently a cop-out for people who don’t want to face hard realities around things like labor or institutional credit, the fact of the matter is that a lot of how DH came to be what it is lives inside the heads of people who are alive today. (“But only for now,” as the deranged Muppets would note in the musical “Avenue Q”.) DH is people. DH is relationships. DH is tools, but no less is it people, and narratives, and t-shirts that mean so much regardless of whether they’re worn at the gym or every possible occasion.

We knit together “digital humanities” through these small exchanges and moments of connection, be they in person, in GitHub issues, on Twitter. One of the first times Roopsi and I talked, before the Data-Sitters Club, before any of this, was over the fact that the live TV broadcast of the musical “Rent” changed some of the lyrics that both of us knew by heart.

And so it seems fitting to end my piece of this book with lyrics from another musical, “Into the Woods”:

Sometimes people leave you, halfway through the wood.

Do not let it grieve you.

No one leaves for good.

You are not alone.

No one is alone.

Suggested citation#

Bessette, Lee Skallerup, Quinn Dombrowski, Maria Sachiko Cecire, and Roopika Risam. “DSC #13: Goodbye, Friends, Goodbye.” The Data-Sitters Club, May 18, 2022. https://doi.org/10.25740/jq417jv3351.