DSC #7: The DSC and Mean Copyright Law#

September 22, 2020

https://doi.org/10.25740/jw434mm1467

https://doi.org/10.25740/jw434mm1467

It all started with a comment on the draft of DSC #5: The DSC and the Impossible TEI Quandaries.

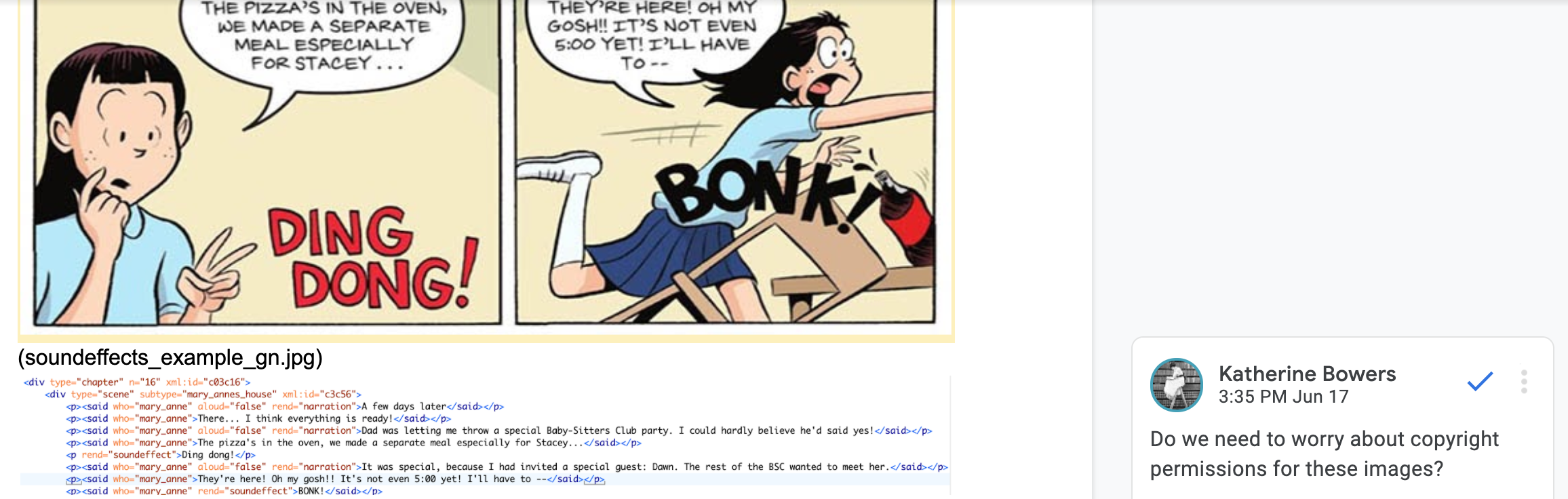

That’s how we do things in the Data-Sitters Club: we each write things, and we all edit together. (What’s the Data-Sitters Club, you may be wondering? You can get all caught up in Chapter 2.) This time I was pretty confident that our use of a couple panels from the graphic novels was legit, and didn’t need any special annotation or justification. But I could see where Katia was coming from. Ever since I started the Data-Sitters Club, copyright has been an issue that’s haunted us like the ghost of Old Ben Brewer in Karen Brewer’s attic. We thought we understood it well enough to stay out of trouble, but it still made us uneasy.

Luckily, I was on my way to Building LLTDM (Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining), an NEH Institute on copyright, licensing, ethics, and that whole swarm of issues that can make you lose sleep when working on a computational text analysis project!

I’ve been a copyright nerd since college (in the 2000’s), counting down the years until 2019, when the evil spell of the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act would be broken and new things would enter the public domain. And I was there at the Internet Archive, wearing a dress made of newly public-domain images from 1924, when that day came.

In the spirit of the Data-Sitters Club, I’ll start from the beginning. But first I need to introduce a special guest data-sitter for this book: Matthew Sag. Matthew is a law professor at Loyola University Chicago School of Law and a leading expert on copyright law and fair use. Matthew has friendly blue eyes, a diamond shaped face, and an Australian accent smoothed over from 20 years living in the United States. He had blonde floppy hair like John Denver when he was a kid, but now he looks more like a clean shaven Jude Law.

Let’s face it: being a copyright nerd helps when it comes to doing DH, but when I got to talking with Matt about our copyright uncertainties while I was at the Building LLTDM workshop and he offered to help out, I started jumping up and down with joy. When he even read some of the Baby-Sitters Club books to get up to speed on our subject matter, I knew I’d found the right law professor for the job!

So let’s dive in together, me and Matt.

What exactly is copyright?#

Most people, if asked casually, would probably say they know what copyright is. But then there are moments when cracks begin to show. If you read fanfic, for example, you’ll likely come across disclaimers like “no copyright infringement intended” – almost like some legalistic twist on “no offense intended”.

Here’s the deal: anyone who makes almost any type of creative work immediately has a set of exclusive rights pertaining to that work.

The “creative” part is important: you can’t copyright facts. Fan wikis (like the one we scraped for metadata about the BSC books in DSC Multilingual Mystery #3: Quinn and Lee Clean Up Ghost Cat Data-Hairballs) depend on this: there’s nothing copyrightable about the fact that Ann M. Martin wrote Kristy’s Great Idea in 1986, it was narrated by a teenage girl named Kristy Thomas, and she refers to her friends Claudia Kishi, Mary Anne Spier, and Stacey McGill. So all that information, plus a plot synopsis, the ISBN number, publication date, and various other details can be included on fan wiki pages. But the fan wiki can’t post the full text of the book, because that’s the creative work itself.

Similarly, a simple list of ingredients and preparation instructions isn’t copyrightable, but the further the recipe skews towards personal narrative, the more likely it is to be eligible for copyright. But even then, copyright would protect only the narrative parts (the original expression) and people would still be free to copy the fact and instruction parts.

As a creator, you have exclusive rights#

We think of copyright most often in the context of formally published works (e.g. books, songs, movies), but it applies equally to, for instance, the first scene of a play that you scrawled in the margins of a course reading while you’re bored in class.

Copyright does not give the creator total control over every conceivable use of a work. It gives creators the right to: Reproduce (i.e., making copies of) the work: if your roommate finds your class notes and types up the script without your permission, they’ve violated your copyright.* Create derivative works based on the work (i.e., to alter, remix, or build upon the work): if your roommate reads the script and is inspired, and goes on to write the rest of the play without your permission, they’ve violated your copyright.*

Distribute copies of the work: if your roommate takes a picture of the script with their phone and texts it to friends (regardless of whether it’s to praise you or laugh at you) without your permission, they’ve both copied and distributed your work. (That said, they might argue that laughing at you is actually an act of literary criticism that should be covered by fair use – I’ll get to fair use a little later.) .

Publicly display the work: if your roommate rips the sheets with the script off your course reading and staples them up to the dorm message board without your permission, they’ve violated your copyright. (If they took pictures of the pages, or transcribed the script, and posted copies of that all over campus without your permission, they’ve “reproduced the work” “distributed copies of the work” and “publicly displayed the work”).

Publicly perform the work: if your roommate and a couple friends have a few beers and decide to have a dramatic reading of your script in front of their friends without your permission… you see where this is going.

* Matt made me add “subject to any applicable defenses.” Of course.

Copyright feels like it lasts forever less one day#

How long do these exclusive rights last? Well, if you’re Alexander Hamilton, working under the Copyright Act of 1790 in the United States, you get 14 years – and if you’re still alive at the end of those 14 years (sorry, Hamilton) you can apply for one copyright extension of an additional 14 years. After that, your work is in the public domain, meaning that it’s unencumbered by copyright and people can use it however they like, without even having to credit you. (Like me, printing all those 1924 magazine covers on fabric and sewing them into a dress.)

In the US in 2020, copyright applies to anything created after 1978 for the lifetime of the creator – plus 70 years. (For things created before 1978, it can get a little messy, but is similarly a very long time.) So, maybe your roommate’s grandchildren or great-grandchildren could do whatever they want with your script, depending on when you die. (The EU has the same copyright term, 70 years after the death of the creator, and in Mexico, it’s life plus 100 years! Katia gets off easy in Canada, with a term of just 50 years after the death of the creator.)

If you’re doing the math and realizing that this means that something you scribbled down in college would, automatically, have restrictions placed on its use for 140 years or more (assuming you have a long life), which all but guarantees it won’t be reused and adapted in creative ways by anyone, ever: congratulations, you’ve found what many people (including yours truly) see as a problem with modern copyright law! In fact, a 2009 paper by economist Rufus Pollock suggests that the optimal copyright term for maximizing economic benefit to both the creator (payoff for creating the work) and society (because society does benefit from others’ creative reinterpretations of works) is… about 15 years, very similar to what was codified in the Copyright Act of 1790. Imagine a world where anyone would have the legal freedom to turn Kristy’s Great Idea into a hit Broadway musical in 2001. Under current law, that’s not possible until after 2090 at the earliest. (And that’s with a bad outcome, like if Ann M. Martin were to fall victim to COVID-19 this year.)

The limits of copyright#

A work being in copyright means that there’s very little you can legally just do with no questions asked.

“I would say ‘limits what’ because saying ‘very little’ only increases the struggle to get people to embrace the full scope of their fair use rights,” Matt interjected. “If we are in the world of pure personal non-public uses, there is a lot you can do without further permission. Non-public performances, silent reading, partial copying for critical or educational purposes…”

I rolled my eyes. “Silent reading? I mean, duh, you can read silently, but is that even worth counting? That’s like, if my kids complain they’re bored, and I’m like, ‘well, you can breathe air’. It’s not even worth enumerating!”

“You say the right to breathe is not worth enumerating, but you won’t someone tries to take that away from you!”

“Come on, do people actually try to use copyright to prevent others from reading things?”

“Maybe not you, but if you are a person with a disability, then sure, all the time1,” Matt replied. “I use text to speech software quite a lot and most major publishers would argue that this violates their copyright (it doesn’t because it does not create a fixed copy and it’s not a public performance). Publishers sued Amazon to limit the ability of Kindle books to do this without their permission.”

Yikes! I hadn’t thought about the intersection of copyright and accessibility. I guess the right to read – even if that takes a different form – really is worth enumerating.

Anyhow, on the other hand, work being in the public domain means you can legally do basically anything with no questions asked. But what about the space in the middle, where the legality depends on the details of what, exactly, you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and how? Under US copyright law, we’re getting into the gray zone of fair use.

What’s fair use?#

The UK (where my fellow Data-Sitter Anouk Lang lives) and former British colonies (e.g. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, Singapore) have as part of their copyright law something called “fair dealing” – which enumerates a specific and finite list of uses of in-copyright works that do not count as copyright infringement. What, exactly, makes it onto that list varies from country to country, but common examples include:

Research (like the Data-Sitters Club)

Private study

Review or criticism

Judicial proceedings or professional legal advice (lawyers look after their own!)

Reporting the news

Parody (and in some places, one or more of: caricature, pastiche, or satire) (lawyers like to laugh?)

To make it as fair dealing, a use has to fit one of these purposes and be seen as “fair.” So the list is a best-case scenario: it shows what might be allowed, if it meets a general test of fairness as the courts understand it.

In the US, instead of “fair dealing” we’ve got something called “fair use” Fair use is similar to fair dealing, but with a twist: the list of examples that can count as “fair use” is, crucially, not finite. The Copyright Act lists a few illustrative fair uses: criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. But the good news is that the list is not closed—things that don’t fit neatly into those categories can still qualify as fair use. The bad news is that, just like with fair dealing, the list is no guarantee either. This is frustrating from the perspective of clarity (there’s no definitive list of things that “count,” so a lot is left up to interpretation and judgment), but it makes fair use broader and more flexible.

Fair use is not black-and-white: instead, any particular use that would appear to violate one of the exclusive rights provided to the author by copyright can be evaluated for “fairness” along the following axes…

Now it was Matt’s turn to roll his eyes. “Okay. Enough of this ‘fair use is a gray zone’ stuff. True enough, fair use is not black-and-white like the rule in the US Constitution that says that you have to be at least 35 years old to be President. There is not much in law that is mechanical and clear cut like that. Fair use is more of a standard, like the part of the Constitution that bans ‘cruel and unusual punishment.’ What you have to understand is that even when the law starts off as a vague standard, rules and principles emerge from the cases that make it much clearer over time. I don’t like the constant refrain that fair use is a gray zone because it ignores the fact that there are many many uses that are clearly fair use, we just don’t talk about them much because they are so uncontroversial.”

I was taken aback. I’d heard the “gray zone” framing so often that I’d assumed that was an uncontroversial shorthand for the situation with fair use. It was even kind of reassuring: the unavoidable ambiguity meant that what might look like a “no” could actually be a “maybe” – even if it also meant that there also was never quite a “yes”, and it all came down to telling a good story. But what Matt was saying was that some stories had been told and validated enough times that they had become truth. I wanted to know more.

The factors of fair use#

Like a lot of copyright law, the fair use doctrine began with judges filling in the blank spaces in the vaguely worded early copyright acts in England and then in the United States. In 1976, the US Congress finally got around to recognizing fair use in the text of the Copyright Act, in Section 107. That section was meant to restate and continue the common law tradition of fair use, but it also included four “factors” to be considered in applying the doctrine.

Those factors are:

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes, and to what extent the use is “transformative”

the nature of the copyrighted work (usually, the fair use argument for responding to a published work is a bit stronger than responding to an unpublished work)

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole (e.g. publishing a quote or excerpt will be viewed more positively than publishing the whole thing, but it’s not just a math formula, you need to assess how much was used in light of the type of work you are dealing with and the purpose of the use).

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work – is your use making it less likely that people will purchase the copyrighted work, or access it in another way that would result in the copyright holder getting paid (e.g. music streaming service vs. pirated mp3)?

“Promoting progress”#

“There is SO MUCH CONFUSION about the four fair use factors. Let me see if I can help,” said Matt. “I don’t think people can understand fair use without trying to wrap their heads around the question of ‘what is copyright really for?’ Luckily, I think I have some answers. Copyright is meant to ‘promote progress’ (it’s there in the Constitution), but the question is how?”

“Yeah, there’s a lot you could problematize there…” I mused.

“At its heart, copyright law is concerned with the communication of an author’s original expression to the public. Original expression is what makes something copyrightable in the first place, and the bundle of rights that copyright gives you are all concerned with the communication of original expression to the public. So, authors don’t get total control over every aspect of the work, they get to control when and how their original expression is communicated to the public.”

“Huh. Okay, but how does that interact with fair use?” I asked.

“By and large, the things that courts have recognized as fair use involve some technical act of copying, but in a context where this copying is really unlikely to interfere with the author’s interest in being the one who gets to communicate her original expression to the public. Such uses are usually seen as ‘transformative’ in that they are for an entirely different purpose, usually a purpose like parody of the original that the original can’t fulfill. A transformative purpose is really important to establishing fair use under the first factor mentioned above, but also under the fourth factor because uses that are really different to the original and couldn’t be fulfilled by the original obviously don’t pose much threat of disturbing the market for the original.”

“Gotcha. So, since Ann M. Martin and associated ghostwriters were creating original expressions specifically with the goal of entertaining and (as our children’s literature scholar Data-Sitter Maria would note) educating children, rather than explicating computational text analysis methods and researching their corpus of texts, that helps make the case for a fair use argument for any excerpts of those original expressions the Data-Sitters Club publishes in the course of our work?”

“Exactly! The original books were meant to be enjoyed as literature and to impress a bunch of subtle and not-so-subtle cultural messages on the impressionable minds of children. If you made one of the books into a musical it would be something new, but you would still be using the author’s original expression for basically the same expressive purpose. That is not cool, or at least it’s way more problematic.”

I had to interject. “I mean, that would be really cool… but yeah, I can see how a musical for children about the same characters and content has the same basic purpose.”

“Right,” Matt agreed. “But the DSC is using the original Baby-Sitters Club books for an entirely different purpose. It’s easy to recognize the use of small extracts embedded within a broader comment on/analysis of the original work as fair use. And copying entire works into a database for computational analysis is actually an even easier case, because original expression goes in one end and fairly abstract and uncopyrightable metadata comes out the other end. Again, this use is really different so we could call it transformative if you like, but more than that, it doesn’t actually communicate any of the original expression to the public.”

“But this only works because we’re researchers, and publishing our ‘books’ online for free, right? If we decided to write The Data-Sitters Club Computational Text Analysis Textbook and didn’t publish it open-access, but somehow it was a huge hit and we made some money, would we be running a risk if we had included parts of our Baby-Sitters Club book corpus in that textbook?”

“You’re asking if fair use has to be non-commercial, or educational, or for research, or some other socially laudable activity? No. Sometimes these things help make the case (and there is generally a bit of extra latitude for educational uses), but no, it’s not required. A use does not need to be noncommercial or for research purposes to be transformative or to be fair use. In fact, some of the most important transformative use cases are about commercial uses.”

“Ooh, like what?” I asked with inordinate interest. (Sorry, copyright nerd.)

“Well, in 1994 the Supreme Court overruled the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals when it said that 2 Live Crew’s parody of Roy Orbison’s rock ballad ‘Oh, Pretty Woman’ couldn’t be fair use because it was commercial. That’s the case that really cemented the concept of transformative use. All the software reverse engineering cases, and the Internet search engine cases are about commercial users doing commercial things. We don’t have much non-profit news reporting in this country, so every time a newspaper successfully relies on fair use, that’s commercial fair use too! So non-commercial use is not required at all, but sometimes the fact that a use is non-commercial can make it easier to see that the purpose is fundamentally different to the work’s original purpose and that it does not interfere with the author’s interest in her original expression.”

“In any case, we should limit ourselves to short extracts from the source material, right?”

“Yes and no. The amount used has to be reasonable in light of the purpose and not so much that it will damage the market for the original work. What’s reasonable will depend on the circumstances. It’s easy to see why if you think about how the third factor feeds back into the first factor and the fourth factor.”

Is it a weird lawyer thing to be able to keep different numbered points straight in your head? What he was getting at was that we were worried about how “the amount/proportion of the copyrighted work” fed back into “the purpose and character of use” and “the effect on the market.”

“If I republish A’s entire work but I call it a parody, then (1) you might begin to seriously question whether it was genuinely a parody after all and (2) you might conclude, that even if it was, it still might interfere with the market for A’s original expression because the parody communicated the whole work. Using too much might harm your fair use case just because you used too much, but the real damage comes from the implications that overuse has for “the purpose and character of use” and “the effect on the market”. How much is enough versus too much depends a lot on the context. I’ll come back to this.”

My copyright nerd inclinations were getting the better of me. “Wait a sec, we’ve talked about three of the four factors. But what’s the deal with ‘the nature of the copyrighted work’?”

“Yeah, I skipped that because when people talk about the second factor they are either explaining why it doesn’t really matter—the Supreme Court said that ‘the nature of the work’ does not ‘help much in separating the fair use sheep from the infringing goats’—, or they are trying to draw distinctions between published and unpublished works, or between creative and informational works that just don’t make any sense,” admitted Matt. “Putting sheep and goats to one side, the notion that the nature of the work is an independent factor in which some works are more deserving of copyright protection than others is just bone-headed. The nature of the work is not really a factor at all, it is just an important part of the factual context in which courts must apply the substantive considerations of purpose (factor one), proportionality (factor three), and market effect (factor four).”

“So what does that actually look like in practice?” I asked.

“Think about the difference between commenting on images vs commenting on text. Images are not less worthy of copyright protection than text, but it is much harder to selectively comment on an image, or use just part of an image as evidence, than it is with purely textual works where you can selectively quote to make your point. So, there are some circumstances where full quotations of an image might be reasonable and proportional where only partial quotation of the text would be allowed.”

“Oooh, good point. So if the Data-Sitters want to dig into the fact that the cover art of the Baby-Sitters Club, and the fact that the style has evolved over the last 20+ years to keep up with contemporary design trends (even if the actual text hasn’t changed much, if at all), it’d be totally legitimate to show the full covers of all the editions of the books, that’d be legit, right? I get it.”

“Yes, that’s a pretty good example … and why is the mean one always wearing a dress?” Matt asked, catching something I’d never noticed before. Maybe Janine’s fashion choices across time and medium needed to go on our list of topics to explore.

“Putting it all together: the Copyright Act has a list of four factors to consider when deciding whether a use is fair, but don’t think of this as a scorecard or a check-list. The factors are all interrelated. If you think about the purpose, proportionality, and likely effect of the use and you shouldn’t go too far wrong. But if you start off thinking that non-commercial use is always good or that full copies are always bad you will get a lot of things wrong.”

It was pretty clear now that when I assured Katia that including a couple panels from a graphic novel in our TEI book was fine on the basis of fair use, I was right. (Phew!) But let’s work through it:

Purpose and character of use#

The Data-Sitters Club is a non-commercial activity with educational and research aims.

“Okay, that’s a good start, but what really matters is that you didn’t just display the original work so that people could enjoy or appreciate the author’s original expression,” added Matt. “You combined it with a whole new layer of analysis, the TEI markup, that added a new layer of meaning and used the original in a totally different way. This is classic transformative use.”

He had a point. It was quite literally transformative, because I’d combined the panels from the graphic novel with a screenshot of the TEI markup, and saved them together as a single image. I could’ve used two images (one with the panels, one with the markup) for the same effect, but making it impossible to download one without the other was one more thing that cemented the ‘transformation’.

“Even better, you aren’t just commenting on the image, you are demonstrating how to apply DH methods using this image as an example. Again, about a purpose that is totally different to the original purpose of the work as a piece of children’s literature.” Matt added.

It’s true, it was hard to imagine how someone would get back to the original work with its intended purpose, from what we’ve put together. As if a parent would point their kid to the Data-Sitters Club and say, “Here, sweetie, enjoy some stories about intrepid girl baby-sitters, just don’t mind all the other text mixed in about digital humanities.” Not happening.

Nature of the copyrighted work#

Matt already dispelled this one. It’s “bone-headed” as a separate factor.

(Fun fact: “bone-headed” appears exactly once in the Baby-Sitters Club corpus, in #107 Mind Your Own Business, Kristy!: “Hey, once in awhile we all do something really bone-headed. Even the great Kristy Thomas.”)

Amount and substantiality of the portion used#

We used less than a full page from the graphic novel: just a couple of panels. You couldn’t even figure out the basic plot based on those panels. Which demonstrates that we really did have an entirely different purpose in mind (transformative use ✅) and also leads directly to …

Effect of the use upon the potential market/value of the copyrighted work#

It’s inconceivable that anyone would say, after seeing those couple panels in our TEI book, “Cool, that saves me from having to buy this graphic novel!” Those couple panels are no substitute for reading the graphic novel, for people who would want to read it already. If anything, I can imagine the work of the Data-Sitters Club – which combines tutorials for DH methods with the Baby-Sitters Club corpus – potentially creating a market of readers for the Baby-Sitters Club series (in its various manifestations) who would not have otherwise considered it. You know, readers like our guest data-sitter, Matt!

The truth about licensing#

So, we’re good, right? There’s no problem for the Data-Sitters Club to include a few graphic novel panels in our books, and we should be free to use the Baby-Sitters Club novels for our research. Thanks, fair use doctrine!

But, of course, it’s not so simple. Fair use isn’t the end of the conversation, particularly with text corpora your university has licensed.

If you’re at a university, you’re probably vaguely aware of the fact that your library pays some kind of subscription fee to publishers for journal access, and may have also paid some one-time and/or subscription fee to publishers for access to licensed corpora – things like the historical archives of the New York Times. You might know that some of these corpora come with terms and conditions like not scraping them (which can strain a provider’s servers); if you’re ever thinking about scraping a resource your university has licensed, please please please go talk to your librarians beforehand. Your librarians aren’t there to police you, they’re there to help you do what you need to do, in a way that won’t lead to the whole university getting their access to these resources shut off. (They’re also often cool people you should get to know anyway, regardless of their utility for your research goals.) When it comes to corpora like Gale Primary Sources that your library may have purchased, all the text files you need might be sitting on a library server somewhere, and all you need to do is talk to your friendly local librarian to get access – much easier than trying to scrape online resources.

Admittedly, the kinds of corpora that commercial data providers (like Gale, which sponsored the online DH 2020 conference) offer are a little different from what we need in the Data-Sitters Club. Understandably, commercial data providers are attuned to the market: what kinds of corpora are enough people interested in that a library might be willing to pay for them? Computational text analysis isn’t a commonly-used set of methods in children’s literature studies – and children’s literature studies is a relatively niche sub-set of literary studies to begin with. To be honest, I didn’t have any exposure to the complications that can come with licensed corpora, until I went to the Building LLTDM workshop – I work in a non-English literatures department, and the licensed corpora widely available to US institutions tend to be in English.

One of the things that is NOT foregrounded about corpora that your university library may have licensed is the fact that license terms can include ANYTHING. Even terms of use that undermine what would otherwise be fair-use-legit uses of the content. And by accessing corpora using your university credentials, you’re bound by those terms. Or at least, you might be. You definitely don’t want to find out that you are, after the fact. Take a minute to think about that: by accessing a corpus your university has licensed, you might be subject to the license terms… which can include RESTRICTIONS on your use that GO BEYOND fair use. Depending on the details of the contract your local librarian has signed, you may not be able to freely exercise the full scope of fair use with regard to how you use the materials in that corpus.

All of which is to say, if you don’t already know the relevant librarians at your institution, and can’t describe off the top of your head the terms for any licensed corpora you use (or might want to use), please stop reading this Data-Sitters Club book right now and go send those librarians a friendly email introducing yourself and asking about a time when you can meet.

It’s okay. We’ll wait.

Did you send the email yet?

I’m actually serious about this, just write a quick email, don’t put it on your list of stuff you might get to later.

REALLY NOW, did you send the email?

Okay, moving on.

DMCA as Buzzkill#

Licensed corpora aren’t the only complication you can face when applying computational methods to text corpora. The copyright experts at the Building LLTDM Institute were fairly confident that copying for text mining purposes would be fair use, even if the material was copied from somewhere a little bit sketchy, like SciHub.This is different from EU copyright law, which requires you to acquire your corpus by legal means. If you’re in the US, you can freely avail yourself of torrents, Russian pirate websites, or mysterious USB drives full of in-copyright literary texts that happen to be left on your porch. As long as you didn’t participate in or encourage the original illegal copying, there should be no problem, no questions asked.

But of course, there’s one crucial exception: You. Cannot. Legally. Crack. Ebooks. (This again differs from the EU, where it will soon be legal to crack ebooks for legitimate computational research purposes. The EU passed a new directive on copyright law in 2019 that comes into effect in 2021.) I cannot begin to tell you how much easier my life would be if it were legal to crack ebooks. For starters, DSC #2: Katia and the Phantom Corpus would’ve been a lot shorter: we could’ve just included some instructions for how to crack ebooks, instead of all that prose about how to scan and OCR paper copies of books (Not to mention, it would have saved us a lot of time not to have to order, wait for the mail, scan, OCR, and clean 225 texts in the BSC corpus!).

Even if your use of those cracked ebooks is totally legit under fair use, it remains illegal to circumvent access control technologies (e.g. cracking ebooks) in the US thanks to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998.

But wait! It gets more complicated!

Every three years, the Librarian of Congress gets to issue specific exemptions from the DMCA. These exemptions only last three years, so if it’s not renewed during the next period for issuing exemptions… it goes back to being illegal. And if you find any tutorials about how to circumvent access control technologies, you have to check the date it’s posted, the most recent Librarian of Congress review period, and today’s date, all to figure out if it’s still legal. The whole system is, legit, a complete mess, but here’s the list of the 2018 exemptions that should be applicable still in 2020.

Anyhow, another one of these rulemaking events will happen in 2021. And the organizers of the “Building LLTDM” NEH-funded workshop I attended include folks associated with the Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic at UC Berkeley, who are filing an amicus brief to support a new exemption from the DMCA that would enable legal ebook cracking for research purposes. Fingers crossed!

Acting boldly#

So this brings us back to the Building LLTDM workshop where I met Matt. The biggest take-away point for me was that the standard advice on copyright doled out by libraries (sometimes with backing from the university’s general counsel, whose job is to keep the university out of hot water, not figure out a way to make your project possible) really tends to be conservative, even when it’s not transparently so. Getting the copyright door slammed in your face is an invitation to dig deeper, because it can’t possibly be that simple. But the “fair use is a gray area” dance is just plausible enough to believe. “It’s complicated” is too often short for “It’s too complicated for you to understand and you don’t want to risk making a mistake.” But talking to Matt helped me see the other side of it: “It’s complicated enough that what might look like a smooth surface of prohibition at first glance actually has grooves and wrinkles where you can get a handhold for doing more things than you might imagine, in a legally defensible way.”

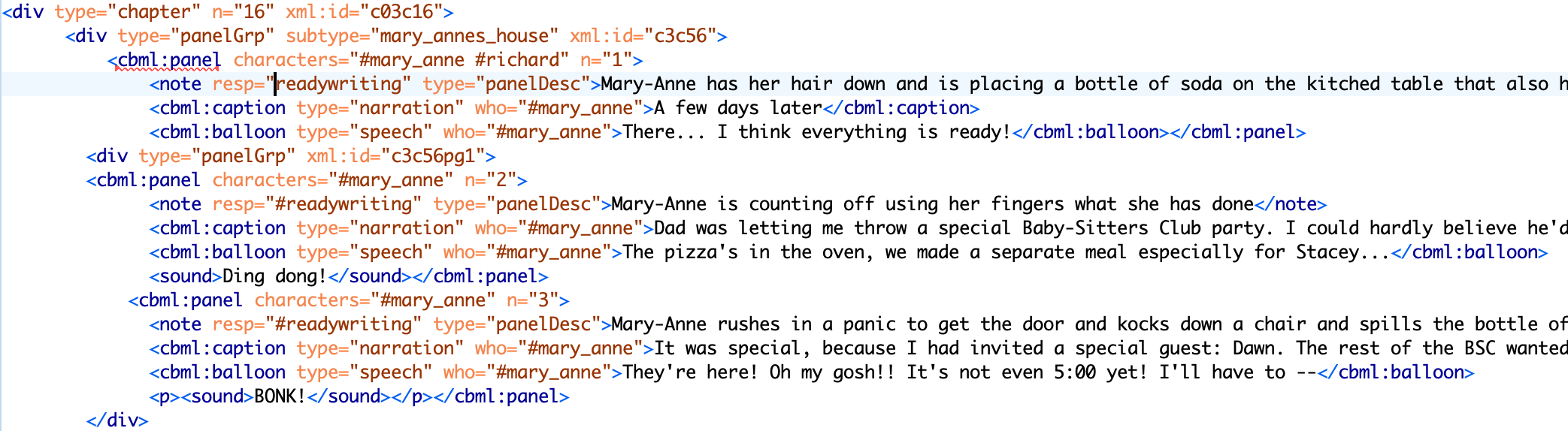

This got me thinking. I’d spent a ton of time transcribing the dialogue and sound effects from the Baby-Sitters Club graphic novels – not just in English, but also in French. It wasn’t just a plain-text transcript, even: I’d put in the time to mark the speaker of each piece of dialogue. And when Lee did her sample of TEI markup, she took it even further by describing the visuals of the graphic novels themselves.

We’d resigned ourselves to all that work having a limited pay-off – limited only to the Data-Sitters Club. We hadn’t dared dream of what it might look like to take more of a proactive fair use stance… until now. I had to run this idea by Matt.

“Realistically, who buys a graphic novel just for the dialogue, right? (Unless they’re a Data-Sitter, of course.) The TEI files we created in DSC #5: The DSC and the Impossible TEI Quandaries… are those files we could possibly share?” I asked him. “I’d assumed there was no way for us to share them, because they’d contain all the text of a graphic novel… but a graphic novel is so much more than just the text.”

“Hang on, before we dive into the legal analysis we need to take a step back and be clear about what these files are, and why you would want to share them,” said Matt. “So, If I understand what I read in DSC #5, the TEI files are essentially a set of structured annotations about an underlying work that exist in a text file that is both human-readable and computer-readable.”

“One could get a little snarky about how ‘computer-readable’ TEI ends up being in practice, but yeah, that’s the idea,” I replied.

“In this case the works are BSC graphic novels, and the annotations include the text, but also add commentary and description on textual and non-textual elements (i.e., they tell you about the words and the pictures).”

“To varying degrees. There’s a lot of different ways you can do TEI markup. I went for something pretty minimal that’s mostly just text, with speaker annotations and a small amount of added information about the text, like if it’s a sound effect. Lee did something more elaborate that included description of the images.”

“Okay, so let’s think about why you want to share these files, how you want to share them, and with whom? One reason you might want to make the TEI files available is to demonstrate the validity and reliability of your coding schema. If you’re going to be using the attributes and classifications in the markup files to make empirical claims about the corpus as a whole, making the source data available will let people examine your initial coding decisions for themselves to make their own assessment of whether your annotations make sense and whether you applied your coding schema consistently.”

This felt like one of those classic “social science vs. DH” moments. It’s not like it’d be a bad thing to make the data underpinning our analysis available so that people could see how exactly we did the TEI encoding. But that’s definitely not what was motivating me here. There’s an understanding that a lot of humanities work is interpretive, and because of that, there isn’t so much of a culture of “showing your work” as you get in the social sciences. We tend to trust one another to not have done sloppy, careless work, but beyond that, differences in encoding are more about differences in interpretation than something you’d want to call “valid” or “invalid”.

“A different reason you might want to make the markup files available is that they would be a cool resource for the scholarly community!” Matt suggested. Now we’re talking! “If the TEI files are available, then anyone else who is interested in this part of the BSC corpus can undertake their own digital humanities research. Also, anyone using the DSC to teach digital humanities methods will be able to run their own analysis and use it as a training text for students.”

“Exactly!” I exclaimed. “There’s so much work that goes into putting together text corpora – even just finding and OCRing books takes a long, long time. I want as many people to benefit from that work as possible, especially when it involves another layer of tedium like doing TEI markup.”

“Okay. Now that we’re clear on the reason for sharing, we can dig into the fair use question,” Matt replied.

Purpose and character of use#

“The Data-Sitters Club is STILL a non-commercial activity with educational and research aims. Our TEI markup of the dialogue is transformative – and it’s even more transformative if it were to include a layer of interpretation, like what Lee offered in her CBML-flavored markup of the graphic novels. In this scenario, more transformative is a good thing,” I proposed.

“Exactly! The TEI markup of the dialogue is transformative because it takes part of an existing work and fundamentally changes it through the addition of multiple layers of interpretation, commentary and classification. These new layers of meaning are important because they show that although in a very literal sense you are still communicating part of the original expression to the public, you aren’t using it for its expressive value or effect. In fact, you are using it for a completely different purpose, namely analysis of the original. I don’t want people to get the impression that transformative use is limited to criticism and analysis of the original work. It’s just that when we see criticism and analysis it is very easy to see that the purpose of the original and the purpose of the second use are intrinsically different.”

“So it’s really the purpose, more than the educational and non-profit context, that matters here?”

“Yes! The fact that the DSC is educational and noncommercial certainly doesn’t hurt, but it really just underscores the strength of your transformative use argument,” Matt added.

Nature of the copyrighted work#

I initially shrugged this off since Matt dismissed it as “bone-headed” as an independent factor. But even still, he was able to use this angle to shed some more light on the situation:

“Even if the “nature of the copyrighted work” is not a factor at all, it is still an essential input into any fair use analysis. Actually, if this case ever came to trial, we would want the court to really think hard about the nature of the work. The whole reason that you wanted to do this TEI markup in the first place is because a lot of the computational analysis that we apply to text doesn’t work very well for a story told in pictures. We would also want the court to see that even though the markup contains all of the text of the graphic novel, the text by itself is essentially worthless to the books’ intended audience, or pretty much any audience.”

Amount and substantiality of the portion used#

From the perspective of the text, this factor would seem to not help at all. Our TEI markup includes all the text – and this factor favors the use of exemplars, rather than the full thing. But if we’re talking about graphic novels, where the visual element is so important, how much does that change things? 100% of the text means what percent of the work overall? An amount of 100% of the text might still mean considerably less on the substantiality front.

Matt agreed that the graphic novel context was key. “The pictures in a graphic novel are not simply illustrations that complement a story told in words. In a graphic novel, the text is typically just a thin slice of a story that is primarily told in pictures. So even though the markup is a literal copy of all of the text, it’s actually only a partial copy of the integrated work that is the graphic novel. It’s true that the markup contains annotations that relate to the story the non-textual elements are telling, but those annotations are still merely a shadow of the graphics.”

Score! Even 100% of the text of a graphic novel still amounted to a smaller percentage of the overall work.

“When a court looks at the amount and substantiality of the portion used, it isn’t just doing a math problem, there is an important qualitative dimension here as well,” said Matt. “The court has to ask how much of the expressive value of the original work has been used by the would-be fair user and whether that amount was reasonable in relation to the fair use purpose. Sometimes, what is reasonable is a pretty small amount, but sometimes it’s the entire work.

“Although we are looking at copying a lot of text here, the fact that the text does not stand on its own suggests that the amount is still qualitatively insubstantial. Furthermore, given the research use that justifies doingTEI markup, it’s hard to see how you could make the same transformative use without copying all, or virtually all, of the underlying text.”

That made sense. We could illustrate what TEI markup looked like using part of the graphic novel, but to be able to say much of anything about these works, we really needed the whole thing.

“Another way of thinking about the ‘amount and substantiality’ factor is to ask yourself whether you are communicating enough of the work to the public that it’s likely to satisfy any of the general demand for the work as a piece of original expression,” Matt suggested.

It was an awkward way to put it, but I saw what he meant. And working with literature for children made it even clearer. Would our TEI transcription satisfy children to the point where they wouldn’t want to see the graphic novels? Nostalgic fans of the Baby-Sitters Club are another audience, but the first time I opened one of these graphic novels, it was the images that propelled me through the text. I wanted to see what the artists had done to bring the world of Stoneybrook to life. If I wanted the text, I could just read the novels for a richer experience.

Effect of the use upon the potential market/value of the copyrighted work#

So it seems pretty clear that a TEI/XML file is a very different thing than a graphic novel. Particularly for the juvenile target audience, TEI is no substitute for the original work.

Even for myself, as a DH person used to dealing with text in various odd formats, I find TEI files to be a huge pain to read – even separate from the question of what you lose by replacing the drawings in the graphic novel with a written description (what Lee did), or nothing at all (as I did). If a reader of these files knew XSLT, they could strip out the tags, and replace them with some annotation for who’s doing the speaking – turn our TEI into a script of sorts. If you take my approach to doing markup (just the text), you end up with something significantly less than the graphic novel, which helps with regard to “amount and substantiality”. If you take Lee’s approach, and describe the illustrations, you get something that includes a lot more analysis of the graphic novel and so rates higher on “transformative”.

That transformation, Matt noted, is still not something that most people would consider to be a substitute for the original work. “I don’t even think that these annotations would be a workable substitute for alt-text used to provide audio descriptions for the visually impaired. Even if the annotations did provide this function, that market is so poorly served at the moment that this will just lead us into a whole new fair use analysis on the issue of disability access.”

I clapped my hands with delight at that remark. It was the perfect encapsulation of how “it’s complicated” can be to your benefit as a researcher when it comes to copyright. Our image annotations probably don’t make our transformative use a substitute for the original – but if they did, we gain some protection through the angle of supporting disability access. “Complicated” cuts both ways, and it can cut in your favor.

As usual, Matt had to throw some cold water on my glee by reminding me of the limited scope of this analysis. “If we are just talking about TEI/XML files based on graphic novels, we could probably stop here. The fair use case is really strong: the purpose is transformative, the amount used is reasonable in relation to the purpose and is not likely to provide a substitute for the original graphic novels or any related expressive work based on the graphic novels. But this analysis is very specific to graphic novels. If you were doing markup of a movie you would face the problem that it would be easy to reverse engineer a screenplay from the markup files. Based on the fact that I have seen people selling screenplay versions of popular films in Greenwich Village that looks more like a potential substitute. And of course, a marked-up version of one of the original BSC novels could easily be converted into a literal reproduction of the novel itself, so that is obviously a potential substitute.”

Hrm… so much for emailing the TEI mailing list to encourage everyone to post all their marked-up texts to GitHub ASAP.

“But even so, there are ways of strengthening the fair use argument,” Matt consoled. “One solution would be to limit access to the markup files to people who have an obvious interest in using them for some kind of digital humanities research or training. You would probably want those people to sign something to confirm that they had no intention of misusing their access. The downside is that this sounds like a lot of ongoing administration and it’s not really compatible with making the data available on something like GitHub.”

Tell me about it. Life’s too short to be responsible for maintaining a paperwork trail for every TEI file you share with colleagues, at least without any sort of centralized infrastructure for storing and sharing texts. It makes me really envious of Katia, whose scholarship outside the Data-Sitters Club is on Dostoevsky, who died in 1880 and whose Russian texts are totally in the clear!

“I have a different solution that I think works better in this context,” he offered. “Remember, we are really worried that the markup files themselves are a substitute because they are hell to read? What we are worried about is that some clever coder will extract a substitute from the markup files. So what if the publicly available markup files only contained a random 95% or 98% of the text? They would still be near enough to complete for any research or educational purpose (wouldn’t there?), but these not-quite-complete markup files would be almost totally without value as an expressive substitute. In fact, even though I think that we are already on solid ground with the markup files based on the graphic novels, if you want to be really cautious you could do the same thing and make sure that there was slightly less than 100% of the text of any individual graphic novel.”

🤨

I hated bursting Matt’s bubble, but this did not sound like a great solution at all. Even a very small number of obvious OCR errors are enough to make many humanists edgy. They don’t like being reminded that they’re working with a derivative of an original book, one created by imperfect processes. What if those imperfections distort your analysis? Katia’s Dostoevsky project paid grad RAs to read the full corpus of Dostoevsky’s work and make sure there were no OCR errors so her corpus would be unimpeachable. With OCR errors, though, at least you can see them if you take the time to look closely. But what if you knew that a random 2-5% of your text was just … missing? Maybe we could do something in the TEI to at least indicate some kind of absence, but depending on the kind of analysis you were doing, if you didn’t know what went in the gap (e.g. if it’s a speech bubble, who was speaking), you might end up having to throw out more of the text.

Imagine, for instance, you were looking at every reference to Stacey’s diabetes, to look at the discourse around medical conditions. You might want to capture every line before and after the reference as well. If there’s a blank spot before a reference to diabetes, then you probably have to throw out that reference because you’re missing the context. And for any given blank spot, you don’t know if it included a reference to diabetes. Now, maybe you could try to guess – looking at the overall frequency of references to diabetes, and their distribution, and estimate based on the number and location of the blank spots – but this is starting to sound like a lot of trouble and math. In the social sciences, there’s a culture of being comfortable with and transparent about margins of error in reporting results. Not so much in DH. We generally don’t calculate it and we don’t talk about it. I’m no fan of doing TEI markup, but I’d honestly have to think long and hard about whether I’d use a TEI text with a random 2-5% of the text missing (especially without annotation that something has been removed), or if I’d redo the work from scratch. Would a compromise like leaving out a chapter, and explicitly noting that, work okay?

“Bummer.” Matt sighed. “I think it’s fine to create these markups of the novels for your own internal use, or for well controlled academic and educational use, but I think that posting multiple complete chapters where the text could be reverse engineered might be going too far for most courts.”

And it wasn’t only the courts. Katia was also dubious. “From a research standpoint, what’s the point of omitting chapters, even if you mark it? It would skew your results!”

Guess that’s a no-go on the legal and humanities research fronts.

A non-conclusion#

“Time is change,” Mimi told me importantly.

I frowned. “I don’t understand.”

“As long as there is time, there is change.”

“You mean things are always changing?”

Mimi nodded.

– BSC #7 Claudia and Mean Janine

Mimi’s wisdom applies to copyright and fair use, too. They’re not fixed, immutable things. New laws are passed. Exemptions to the DMCA are granted. Case law shapes the ways we can interpret the laws on the books. As the legal scholars running the Building LLTDM workshop pointed out, fair use is a muscle that will atrophy if not used.

I don’t have a conclusion to this book. We’re not putting our TEI on GitHub… at least, not yet. We don’t have a good reason to; even after 7 DSC books, we’re still just exploring the Baby-Sitters Club corpus and thinking about directions we might take it. The whole picture matters in fair use situations like this. Not just “what” (even though most of the advice out there relates to “what”), but also “how”, and “when”, and “where”, and “why”?

Posting the TEI transcriptions on a website where people go to look for literature to read – even somewhere like the Internet Archive – has different implications than posting the very same TEI transcription in a place where people go to look for data – like GitHub. And posting it in conjunction with a Data-Sitters Club “book,” as a form of research transparency and replicability, is different than posting it – for instance – because I’m annoyed about the Internet Archive pulling all the Baby-Sitters Club and other Scholastic Publishers’ content due to a takedown notice issued in response to the National Emergency Library initiative.

There are other things I could imagine us doing, too. Maybe we could post to GitHub excerpts from the novels, richly annotated for entities (names, places, and the like), to be used as training data for improving automatic entity-recognition algorithms. (If you need a reminder of how bad widely-respected systems can be around entity recognition, especially in languages other than English, check out DSC Multilingual Mystery #2: Beware Lee and Quinn!) after seeing how David Bamman’s LitBank project dramatically improved entity recognition in (public domain) English literary corpora, I want those kinds of results: and I also want it for all the scholars I work with, regardless of their language or time period!

But for today, I’ll wrap up with the thought that copyright law is, indeed, complicated. Seize it by its complexity and use it!

To learn more…#

There’s so much to learn about copyright, fair use (and similar provisions in other countries), licensing, and how to push those boundaries without putting yourself or your institution at too much risk. While, luckily, it’s not a problem for Anouk, our Scotland-based Data-Sitter, to share our corpus or do computational text analysis work, the same isn’t true for everywhere in the world. Before getting too deep into computational text analysis, and certainly before undertaking international collaborations, check out the following resources:

Building LLTDM materials on copyright, fair use, international law, and ethics

Sag, Matthew, The New Legal Landscape for Text Mining and Machine Learning, Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA, Vol. 66 p.291 (2019)

1 For some examples of just a few issues, see Blake Ellis Reid, Copyright and Disability (May 1, 2019). U of Colorado Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 19-16, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3381201

Suggested Citation#

Dombrowski, Quinn and Matthew Sag. “DSC #7: The DSC and Mean Copyright Law.” The Data-Sitters Club. September 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.25740/jw434mm1467.