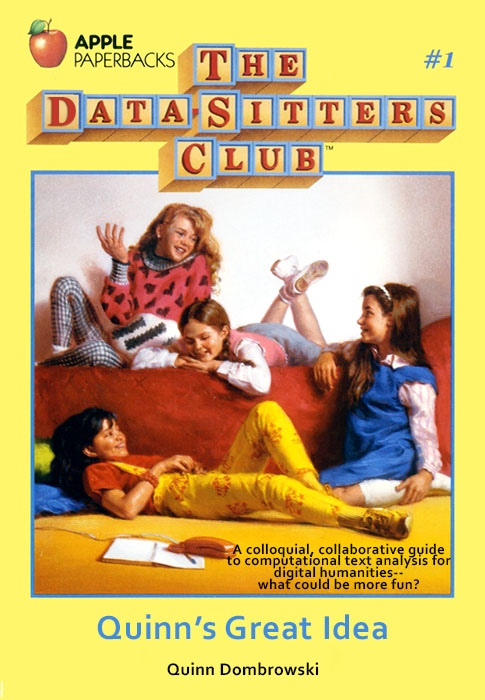

DSC #1 - Quinn’s Great idea#

by Quinn Dombrowski

November 7, 2019

https://doi.org/10.25740/jf827gc7731

https://doi.org/10.25740/jf827gc7731

It doesn’t really matter that it was my idea. I don’t really care about credit— I’ve got what’s half-jokingly been called “the world’s best dead-end job,” and credit doesn’t buy me anything. What matters to me is that good things happen, and this project is a very good thing.

I got the idea while I was on vacation. It was the first vacation I’d taken in four years, and my husband, Andy, and I were happily working on our own projects on the 10th floor of a giant pyramid in Las Vegas. Because it was vacation, I’d promised myself I wouldn’t do anything related to my job — which meant no non-English digital humanities. But by the second day of our trip, my thoughts kept coming back to a blog post about The Baby-Sitters Club (BSC), featuring my friend Shannon Supple, who stewards Ann M. Martin’s papers at Smith College. Some of my projects involve fanfic, and I’d already written a Jupyter notebook to scrape fanfiction.net, so I first thought I’d just grab the metadata for English-language BSC fanfic and throw together a few visualizations. But I’ve been spoiled by the size of the Harry Potter fanfic corpus (nearly 800,000 — 100x bigger than the BSC’s 800) and wasn’t feeling inspired.

Then I started searching for the full text of the original novels — and I found some. And then I found more. (It seems like lots of libraries didn’t think twice about getting rid of their copies, and the Internet Archive took in the cast-offs.) Before I realized it, I was on a quest. That whole week in Las Vegas, I slept in until a luxurious 7:30 AM, braved the pyramid’s morning Starbucks line, and mostly spent the rest of the day searching for BSC novels, when Andy and I weren’t out enjoying Las Vegas — and sometimes even when we were. More than once, we noticed we were the only two nerds sitting in a pub with laptops open. Look, that’s our idea of a romantic getaway. We’ve been married 12 years, and as of this year, we’ve known each other for about half our lives, since we met as incoming undergrads at the University of Chicago. But I guess I’m getting ahead of myself, as I often do.

Hi! I’m Quinn Dombrowski, the DLCL ATS (or Academic Technology Specialist in the Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages) at Stanford University. Essentially, I’m a half-library, half-departmental staff person who supports and implements non-English digital humanities scholarship.

I’m short (about the size of a 10-year-old), with short brown hair, glasses, and the same light blue eyes as my three kids (ages 5, 3, and 1). You might think that with so many kids, I enjoyed babysitting when I was a teenager, but you would be wrong. The one time I ventured into the promised land of fun and profit as depicted by the BSC, I discovered that I hated it, and it didn’t even pay as well as building websites. Such was my introduction to gendered labor. I built a lot of websites, but never once changed a diaper, before giving birth myself.

At least in English, I identify as non-binary, but I have no preference whatsoever about pronouns. Grow up in the 1990s with a name like Quinn, and you get used to lots of different pronouns. I do care about nouns (person not woman, parent not mother), but explaining all that is an awful lot to stick in an email signature or on a conference name tag. My kids call me “PG,” short for “progenitor/progenitrix.” I sew all my own clothes — everything (and I do mean everything), except socks. Dressing in bright colors and interesting prints (Eyeballs! Dinosaur-Unicorns! People being tormented by demons in illustrations from Russian folk tales!) is more important to me than androgyny, so when I’m at work, I only wear dresses with enormous pockets. Even in formal contexts like Stanford’s literature departments, you can wear absolutely anything if it’s in the shape of a dress. At home in Berkeley, it’s all pants and sweatshirts — always in colorful prints (Sailor Moon! Fraggle Rock! Octopi!).

(Here I am, reading a Baby-Sitters Club book in my backyard, c. 1992!)

So there I was in Las Vegas, sipping on a beer, building a BSC corpus — and as usual, tweeting about it. On the geopolitical stage, it’s hard to argue with the claim that Twitter is a force of evil. But Twitter is also the infrastructural backbone of much of the digital humanities world. It was on this same trip that I realized that Twitter gave me the community of friends who share my weird interests that I’d dreamed of since reading the BSC books as a child. One notable thing about tweeting about the BSC is who replies: it’s all people who experienced girlhood in the 1990s. The first BSC book came out in 1986, and the last in 2000 (not counting The Summer Before, which was published a decade later). If you grew up female in the Anglophone world, and you’re in your 30s or early 40s, these books are a cultural touchstone — even for people like me who moved on to other franchises (Star Wars novels, in my case) by the time they hit puberty.

Over the course of the week, lots of people were generous in answering the more technical questions I had when playing with this emerging corpus (like — ugh — is it normal for the top 20 words for every single topic in a topic model to just be names?), but I was surprised and delighted to find pools of interest in the books themselves among my digital humanities Twitter friends. And not just interest, but expertise: Roopika Risam, in addition to being a brilliant postcolonial digital humanities scholar, is also a walking encyclopedia of BSC. The more people threw ideas out on Twitter, the more sure I was that I was on to something, that the BSC is, in fact, an amazing potential laboratory for computational text analysis.

Think about it: there are over 200 novels, all written in the voice of one (or multiple) characters, by Ann M. Martin or a clearly identified ghostwriter. (There’s no one I need to gratefully acknowledge for their help in preparing this manuscript, because I wrote it myself, thank you very much.) Does each character have a distinct voice? Is that voice different across writers? Do non-narrating characters have distinct voices expressed through their dialogue? How does the characters’ written language (through the handwritten portions of the text) differ from their implicitly spoken text through the first-person narration? The BSC is (in)famous for its use of tropes (Claudia’s “almond-shaped eyes”, “Mal is white and Jessi is black”, etc.), so what else can we find in terms of explicit text reuse in the more formulaic parts of the book (the “Chapter 2” question, AKA “how many different ways can you describe the basic premise and major characters across 200+ novels”)? How do these books treat religion, race, adoption, divorce, disability, not to mention the “Very Special Episode” topics? And all that is just the books: what about how the material was adapted for the 1990’s show, the movie, the new graphic novels, the upcoming Netflix series, and the fanfic? There’s unexplored material for a whole research agenda in the area of cultural analytics, which could really use a teenage girl lit counterbalance to its superheroes and sci-fi.

But what if a project did more than just analyze these books? What if it actually walked through the whole process? A year ago, when I started this job at Stanford, I’d done digital humanities for nearly 15 years but had never done computational text analysis. The internet is littered with workshop materials, tutorials, and Python and R scripts with varying levels of documentation, but I had trouble putting all the pieces together. My question to folks at Stanford’s Literary Lab, again and again, was “so what do you actually do next?” And what I learned was that what lies behind the glossy final graphs isn’t a paved road, but a series of choices that shape a walk through the woods. Yes, there are some things (particularly with statistics) that you can unambiguously do wrong, but in most contexts there isn’t a right choice — it’s more like each possible decision provides a different set of opportunities and constraints for your analysis. Some of those constraints make a difference, some of them don’t, and it all depends on what you’re trying to do. At a “Women and Gender Minorities in Digital Humanities” event at Stanford last May, Nichole Nomura — a member of the Literary Lab, and my co-director at Stanford’s Textile Makerspace — brought up the “view of the whole” from Lave & Wenger’s conceptual framework for communities of practice, in the context of an alternate model of mentoring in digital humanities: “To mentor and have people join our community, we have to show them the whole work of the whole community. We have to make all our practices visible. Maybe we don’t have to teach them explicitly right away, but they need to be seen.” I’ve been thinking about this ever since, and whether demystifying computational text analysis might make it more accessible for folks who don’t see themselves as programmers, or “the sort of person who does that stuff” (i.e. white dudes with some previous exposure to computer science).

This was the great idea that came together in Las Vegas: to apply the computational tools and methods that are widely used in the digital humanities text analysis community to the BSC corpus, making visible all the steps and decisions that shape that path. And to write the whole thing up in a series of detailed but colloquial posts that could serve as a guidebook for fellow travelers. I wanted it to be useful — something that newbies of all genders would consult, regardless of whether they grew up as fans of the BSC. Even in the reality-distortion field of Las Vegas, I was under no delusion that I could tackle this by myself. So I emailed a couple friends who’d chimed in on the BSC tweets, and then a few more.

My vacation came to an end, throwing me right back into getting kids dressed and fed and delivered to and picked up from the right places at the right times; meetings, projects, just enough housework to postpone descent into utter chaos, and the four-hour daily commute three times a week. But this project was the best souvenir I could have asked for. It has some challenges, including language: English is one of the few languages out of scope for my job. But it’s mostly a project for after the kids’ bedtime, and I think that understanding what it’s like to work on a project in modern English will help me advocate for better resources for languages that aren’t English.

So I’d like to introduce The Data-Sitters Club. Need computational text analysis? Save time! Visit the Data-Sitters Club and get the inside story on how to apply digital humanities methods to a real project. So far, there are five of us, and, like the BSC members, we all have different experience and specializations.

Roopika Risam is an Associate Professor of Secondary and Higher Education and English at Salem State University. Everyone calls her Roopsi. Her family is from Kashmir, but she was born in Wales. She actually has two passports. Roopsi has beautiful, clear, Bit-O-Honey-colored skin and black hair, which she wears in a graduated bob with blonde highlights. She grew up in Washington, DC, and she’s dibbly jaded from it. This is probably why Roopsi still wears Doc Martens boots and dresses everyday, like it’s still the 1990s. Her sister, Monica, is a real, live genius. She’s even a member of Mensa. Roopsi’s the black sheep of the family even though she’s the one who skipped Kindergarten. But that really just means she’s not that great at cutting and pasting or sharing. Monica recently admitted that Roopsi is actually the brilliant one. I think that made Roopsi feel pretty good. I’ve known Roopsi for a while but the first time we really connected was when I wrote the first review for her book, New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy. It was fresh and distant.

Katia Bowers is an Assistant Professor and Russianist at the University of British Columbia, so we have some Slavic Studies connections. Katia has curly-wavy light brown hair, brown eyes and glasses. She’s lived all over the world - in Germany, the US, Russia, Croatia, the UK, and now Canada - and when she was a tween, BSC books were a way for her to connect with American culture from abroad. Since moving to Canada she has adopted a kind of Vancouver-style that involves an espresso addiction and a daily uniform of black leggings and tunics or long sweaters. Her clothing might seem nondescript and utilitarian, but she jazzes it up with shoes from her large collection, which has a 19th-century vibe, and she’s often to be found wearing shoes that are historically accurate to the period she’s writing and reading about that day. Katia and I met at the Slavic Digital Humanities Summer Workshop at Princeton in September the week before my trip to Las Vegas. At the workshop, she was talking about a new digital humanities text analysis project she’s doing with Kate Holland at Toronto that focuses on Dostoevsky’s writing, but I didn’t realize that Katia was a fellow BSC fan until she and Roopsi and I got to talking on Twitter.

Anouk Lang is a Senior Lecturer in Digital Humanities in the Department of English Literature at the University of Edinburgh. Her introduction to the BSC books came in sixth grade in Sydney, when their candy-bright spines lit up the shelf of sensible whites and creams that made up the rest of the class lending library, and the race to beat everyone else through the series was on. Somewhat hilariously for someone who would grow up to be a postcolonialist, as a kid she read much more American literature than Australian — Sweet Valley High, the Ramona books, Little House on the Prairie, Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, the Three Investigators — alongside the more normative shelves and shelves full of British English books by the likes of Blyton, Noel Streatfeild, C.S. Lewis, Tolkien, and Douglas Adams. Anouk is probably closest to being a mixture of Mallory’s glasses-wearing awkwardness and Dawn, always figured as geographically other. Her Australian twang has faded after 20-odd years in the UK into a more generic learnt-English-somewhere-other-than-England accent. She can, with effort, code-switch between the different uses of “pants” (US & Australian English = long trousers, British English = underwear), and is gradually adding Scots words to her vocabulary, the most useful so far being “outwith.” She has no hopes of keeping up either with Claudia’s barrette and earring game, or with Quinn’s sartorial creativity in the digital humanities-dress department, but does pull out her beloved Bernina sewing machine from time to time to make things, most recently a black plush Toothless dragon.

Maria Sachiko Cecire is an Associate Professor of Literature and the Director of the Center for Experimental Humanities at Bard College. I actually went to undergrad with Maria at the University of Chicago, and who would have thought we would end up working together later in life? It’s pretty great. Maria is half-Japanese and half-Italian, and has dark brown hair, brown eyes, and olive skin that turns a deep toast color in the summer. She grew up in the South and absolutely loves the beach. She also loves books and has shelves and shelves of them in her house. She’s so interested in children’s literature that she wrote her own book about it! It’s called Re-Enchanted: The Rise of Children’s Fantasy Literature in the Twentieth Century. Now she’s excited about diving back into the BSC.

But Maria is more than a bookworm: she also loves getting out there and doing stuff, especially with her friends. She can be super social. For example, she started an interdisciplinary curriculum and center in Experimental Humanities at the small liberal arts college where she works. The students, faculty, staff, and community members involved in EH (that’s what they call it for short) use all kinds of tools and methods to think together about how technology mediates what it means to be human. It sounds like heavy stuff, and I guess it is, but they have a ton of fun! Maria is always experimenting with different media and coming up with new projects, and if that can involve group calls with her colleague-friends around the world to talk about children’s lit, all the better!

It was the day before Halloween when all five of us were finally able to get together. I had subtly raided my kids’ Halloween candy buckets (from trick-or-treating at businesses the weekend before) before leaving for work, swiping a mix of Almond Joys, M&Ms, and Nerds. (What would Claudia Kishi do as a parent?) The biggest downside to virtual meetings is that you can’t share candy with your friends.

“It’s been really interesting to see how the ideology of the 90’s plays out in these books,” said Anouk.

“It’s such a period piece of suburban girlhood,” agreed Roopsi. “I moved to the US when I was a kid, and Stonybrook is so much like where I grew up, in ‘post-racial’ DC, where everyone pretended there were no structural differences.”

“For me, the structures implicit in the books were the implicit structures around me,” added Katia. “Before I moved to the US when I was 12, The Baby-Sitters Club was my primer on how to be a suburban tween.”

“What I’ve been thinking about has been how The Baby-Sitters Club relates to work on girlhood studies around boarding school books — things like Malory Towers,” mused Maria.

“I was literally just reading those to my kids!” laughed Anouk.

“Boarding school books present this low-stakes environment for practicing how to be a — usually — starkly gendered person in the world outside that little world. I’m curious if there’s any computational way to look at whether The Baby-Sitters Club functions as a ‘little world’, where it’s safe to try and fail, in preparation for the outside world,” Maria suggested.

“Even if some of our questions turn out to not be compatible with computational analysis, it’ll still worth talking about the limits we run into with these methods. Publishing negative results is a good thing!” I replied.

As we went around, thinking aloud about the directions we could explore together, I was delighted. We could actually do this: kids who once read BSC books in our bedrooms, thousands of miles away from one another, were now grown-ups with faculty or alt-ac jobs. We had the resources to ask and answer the questions we were only dimly aware of then, and make visible all the steps along the way.

The Data-Sitters Club was going to be a success, and I helped make it work. I hoped Roopsi, Katia, Maria, Anouk, and I – the Data-Sitters Club – would stay together for a long time.

Suggested citation#

Dombrowski, Quinn. “DSC #1: Quinn’s Great Idea.” The Data-Sitters Club. November 7, 2019. https://doi.org/10.25740/jf827gc7731.