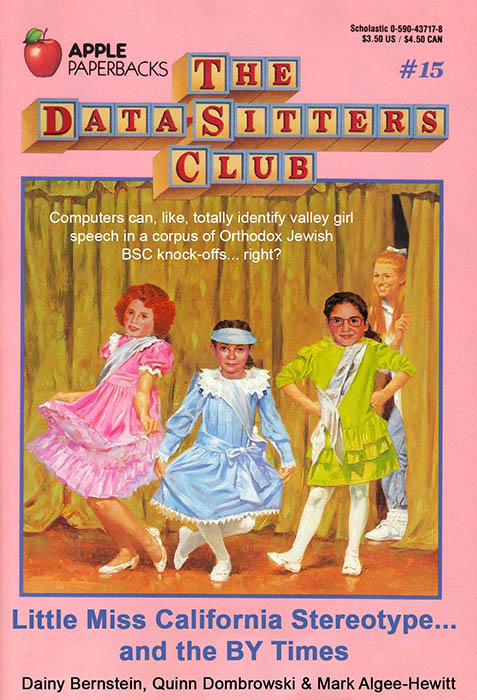

DSC #15: Little Miss California Stereotype… and the BY Times#

by Dainy Bernstein, Quinn Dombrowski, and Mark Algee-Hewitt

September 15, 2022

https://doi.org/10.25740/yf913sr7885

https://doi.org/10.25740/yf913sr7885

Quinn#

Prelude#

The miraculous thing about DH Twitter is how it can bring you the friends you don’t even realize you’re looking for. It’s how I started the Data-Sitters Club (which you can read more about in Chapter 2). I met Dainy Bernstein shortly after the pandemic started.

Dainy is a Visiting Lecturer in Literature at the University of Pittsburgh, and has short, dark brown hair and brown eyes. Ey bounces back and forth between big-picture ideas and detail-focused ideas, sometimes writing about an entire collection of books and sometimes writing three pages about a single paragraph. Eir childhood and adolescence was spent in Brooklyn, New York, reading as many books a week as the public library let er borrow. Dainy writes about ultra-Orthodox Jewish children’s literature and is the editor of the recently-published collection of essays Artifacts of Orthodox Jewish Childhoods.

There’s not that many people working on the intersection of DH methods and books for young readers, so I’m always excited to meet another one. When I realized eir specialty was Orthodox Jewish youth literature, I couldn’t resist asking if ey’d heard of BY Times, the “Jewish answer to the Baby-Sitters Club” as Mara Wilson described it on the Toast.

The resulting DSC 15 has taken over two years to write, between trying to build a corpus of BY Times books when libraries were closed and Inter-Library Loan wasn’t operating (and used copies could run hundreds of dollars), trying to actually read these books with my eyeballs (making lists of questions to send to Dainy), settling on a research question (the depiction of the “California girl” in each series), and then trying a couple different methods to see if we could reliably identify what we felt was distinctive, stereotypical “California girl” speech.

Spoiler alert: it didn’t work. Which is on point for book 15: Dawn’s contestants in the Little Miss Stoneybrook beauty pageant didn’t win, either. But come join us for this interdisciplinary digital humanities adventure anyway, where you’ll see what happens when you combine an expert in a particular literature (Dainy), a curious and bewildered jack-of-all-trades (me), and a computational text analysis expert (Associate Data-Sitter Mark Algee-Hewitt, recently-tenured Director of the Stanford Literary Lab) to tackle a text-classification problem.

Dainy#

Childhood experience reading the BY Times#

My introduction to the idea of the B.Y. Times as the “Orthodox Baby-Sitters Club” came from that same Toast article by Mara Wilson. Mara describes her experience reading these books as a young Conservative Jew, because her Orthodox friend wanted her to become more strictly Orthodox in her practice. She’d explain the series to her gentile friends by saying, “They’re like a Jewish Baby-Sitters Club.” That in itself is a fascinating experience, but my adolescent experience with the B.Y. Times books is entirely different. I had access to both the Baby-Sitters Club series via the public library and my school library, and the B.Y. Times series via my school library and the local neighborhood Jewish library. I can’t say for sure, but I most likely read the B.Y. Times series before I read the Baby-Sitters Club series. To me, as to other pre-teens in my ultra-Orthodox community, the Orthodox books were not perceived as derivations. I didn’t make the connection between the BYT and the BSC until Meira Levinson, an academic colleague who is Modern Orthodox, shared Mara Wilson’s piece with me.

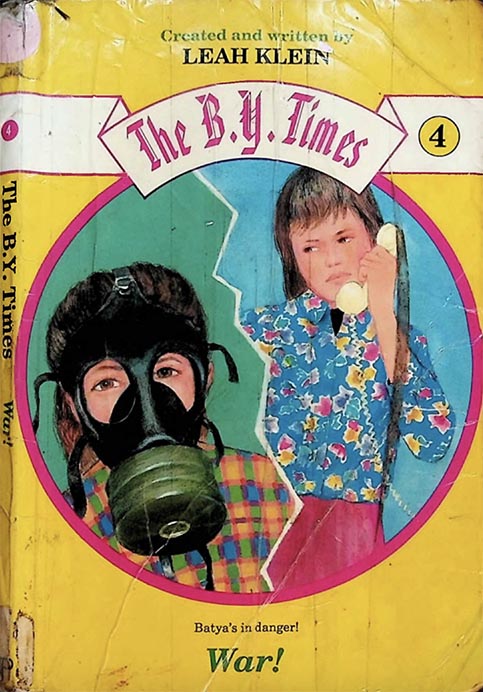

My lived experience is also not exactly like the girls in the B.Y. Times series, mainly because the series - like its sister series, The Baker’s Dozen - is set in Bloomfield, an imaginary New York suburb. I grew up in Boro Park, in the heart of a Brooklyn Jewish community. In the fourth book of the series, War!, Batya Ben-Levi has a conversation with a girl from Boro Park which encapsulates the difference between the two environments as they talk about their respective Bais Yaakov schools (a generic name for Orthodox Jewish girls’ schools):

“So your friends are all excited about having your own Bais Yaakov building. In Boro Park, we have two buildings, and soon maybe there’ll be a new annex.”

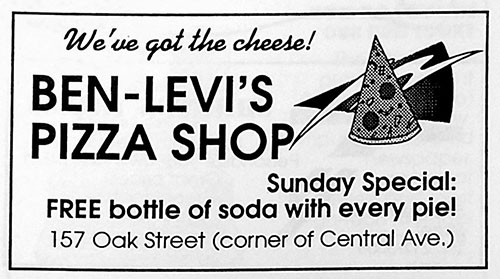

Batya, from the suburban Bloomfield, is excited at the prospect of Bais Yaakov having its own building; her counterpart from the city scoffs at this as a marker of growth since her community passed that marker decades before. The existence of the Ben-Levi pizza shop in the B.Y. Times series is remarked upon as extraordinary within the books, because the infrastructure of a kosher community in a suburban environment was indeed extraordinary at the time, in the early 1990s. In 1990s Brooklyn, the existence of a thriving kosher pizza store was taken for granted.

The difference between Brooklyn Orthodox Jewish communities and the “out-of-town” communities depicted in the BYT - and in the Brookville C.C., a series for older teens similarly based on the BSC - is not always apparent to those who didn’t grow up with these nuances. As Quinn read the series, we’d have exchanges like this:

Quinn [after reading that the Rabbi’s wife in the B.Y. Times series was an original student of Sarah Schenirer]: Who’s Sarah Schenirer?

Dainy: “mother of Bais Yaakov,” founder of the Bais Yaakov movement.

Quinn: Ohhhh. Yeah, that’s another thing I understand badly. 😅 I was figuring it was the name of the school in BYT, like how my kid goes to Malcolm X Elementary in Berkeley. Then I figured it was some educational philosophy, like a Montessori school, since it showed up in both series.

Dainy: I think in BCC they actually go to Beis Rivkah, which is a typically Chabad / Lubavitch name. But Bais Yaakov is a generic name for “orthodox girls school” because of Sarah Schenirer.

Quinn: Ohh, gotcha. The “Beis” is the part that stuck with me because of OCR errors.

Dainy: (Bais/Beis = house, Yaakov = Jacob. It’s from the verse “go tell the house of Jacob” in the Bible, usually interpreted as “go tell the women” in that context.)

Quinn: Ohhhh, interesting.

Dainy: I am so loving “reading” the books through your eyes.

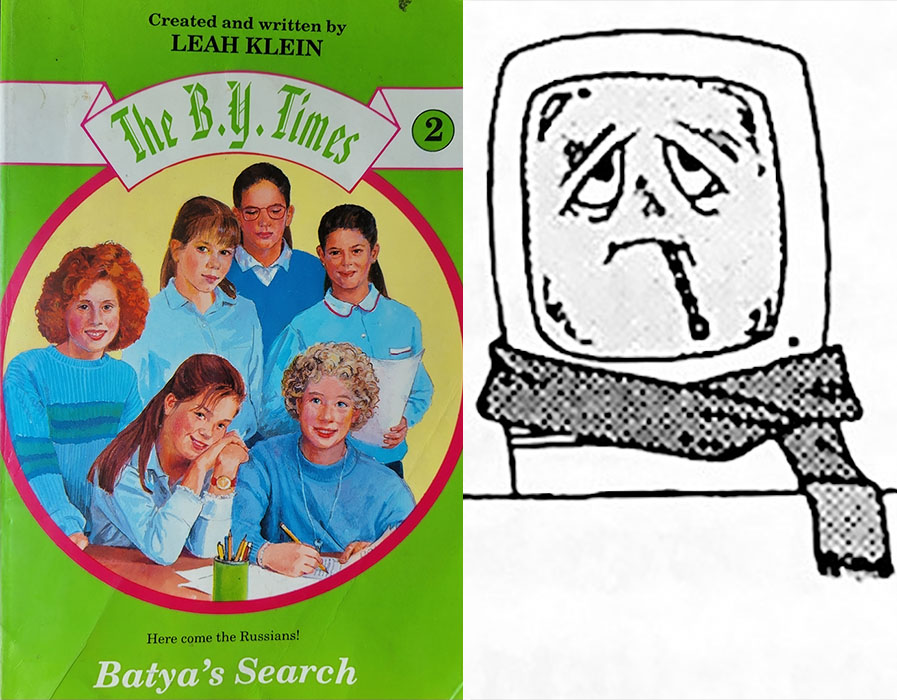

I am rereading these books myself now as I write about the development of Orthodox children’s publishing in America. The earliest Orthodox children’s books from major publishers appeared in the 1980s, making the B.Y. Times series part of Haredi publishing’s relative infancy. I interviewed series creator Miriam Stark Zakon (writing under the pseudonym Leah Klein), and she confirmed that the connections that Mara Wilson and others draw between the BSC and the BYT are deliberate. Zakon had been writing books for Haredi children for a while, and she wanted to get a sense of what was popular for children in mainstream America. Since she was living in Israel at the time, she asked her sister in America to go into a bookstore and take stock of titles and genres on the shelves in the children’s sections. Her sister sent her copies of The Baby-Sitters Club, and Zakon set out to create a “kosher” version of the books for Orthodox children in which middle-school girls create a school newspaper.

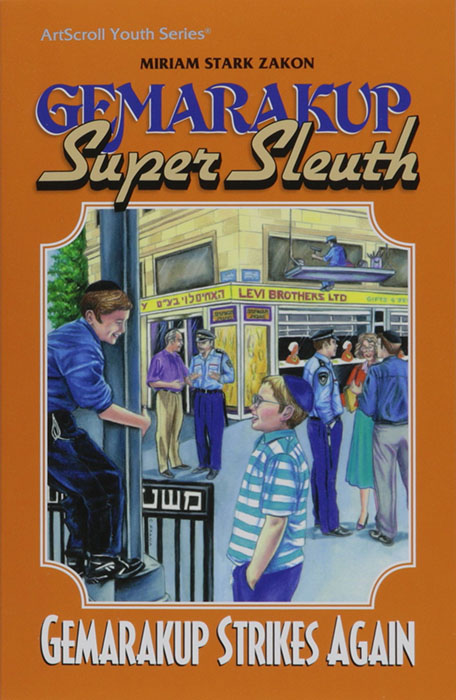

A few other Orthodox series are also clearly based on popular mainstream series. The Gemarakup series (also written by Zakon), for example, is a riff on Encyclopedia Brown. In both, a young boy (Yisrael David Finkel and Leroy Brown, respectively) solves mysteries and crimes in his neighborhood using his extensive knowledge. Leroy (aka Encyclopedia) uses knowledge he gains from an encyclopedia; Yisrael David (aka Gemarakup, literally translatable as Talmud-Head) uses knowledge he gains from the Talmud.

When I first connected with Quinn over the connection between the BSC and the BYT, I hadn’t managed to get hold of any B.Y. Times novels. Copies available for purchase from the publisher are new editions, and I wanted to make sure I was reading the books in their original forms. The used copies available online are prohibitively expensive, and while the Brooklyn Public Library used to carry the books, they have since been retired from circulation.

Once I started working with Quinn, I doubled my efforts to get hold of the books and tried some other channels.

The Jewish Youth Library was founded in February 1978 (according to a writeup in the children’s magazine, Olomeinu / Our World) to fill a gap in the availability of Orthodox children’s books. (This was before the Brooklyn Public Library started carrying Orthodox children’s books.) It started out on 51st Street in Boro Park, Brooklyn, and has since moved to 46th Street, a few blocks over from its original location. As a pre-teen and teenager, I visited the basement library during girls’ hours at least once a month, taking out the maximum of three books at once. It exists in my mind as belonging to another time, and it hadn’t even occurred to me to check if it was still functioning until I mentioned it in passing to Quinn.

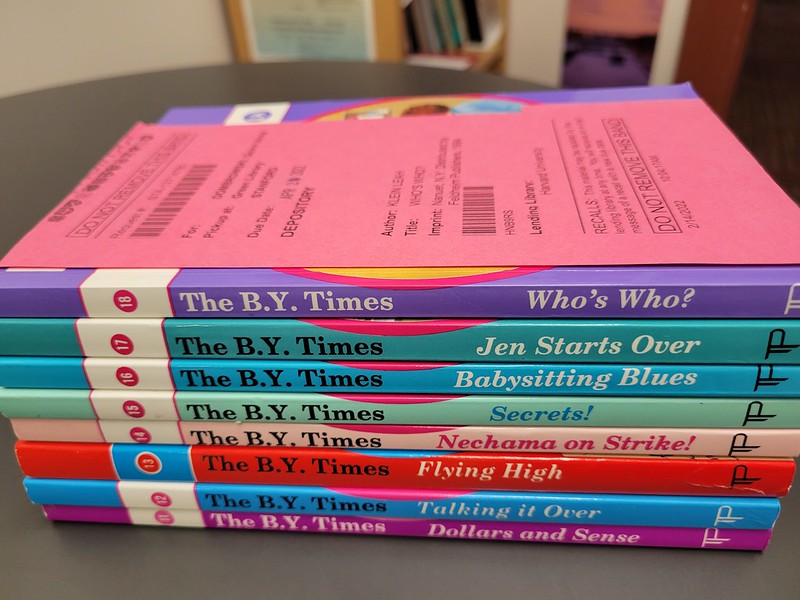

So I called, and they are still functioning! At the start of the pandemic, they were observing social distancing, and all books had to be ordered ahead of time. The library now allows members to borrow five books at a time, extended to six during summer months when kids are not in school. The librarian I spoke to was very patient with me as she updated my decades-old analog membership card - still there along with my mother’s, sister’s, and brother’s! - and listened to what I needed. I explained that I wanted to borrow all the BYT books, and if I could take six at a time, it would be best if I had the first six. She checked on the shelves, and found the second book was checked out by another patron. She pulled books #1 and #3-7 for me instead. A friend of mine offered to drive over and pick them up the next day during curbside pickup, and then drove over to deliver them to me.

Although the books are being reprinted with brand new covers by Menucha Publishers, a newer Haredi publishing house who inherited Targum Press’s old titles, it was important to me to have the original copies of the books because of the extra-textual details often included in books. And the copies from the Jewish Youth Library are indeed the originals! Taped up and worn out from years and years of use… I scanned the books (noting fascinating details like a writing contest for readers announced at the back of some books), and sent them off to Quinn. Since then, Quinn has managed to get copies of the books held in Harvard’s library via Inter-library Loan.

Quinn#

Baby-Sitters meets Sweet Valley, but make it Orthodox?#

Thanks to Harvard’s extensive Judaica collection, we finally pieced together the entire series – a project nearly 18 months in the making. A trip to Greece in April gave me the opportunity to sit down and read through them all, and thanks to Mara Wilson’s article, I brought a truckload of assumptions with me. Newspaper angle aside, this was going to be the Orthodox Jewish Baby-Sitters Club. I was on the lookout for Kristy, Claudia, Mary Anne, and Stacey, ready for whatever they looked like transposed into a new cultural context.

Except it turned out things were more complicated. BY Times isn’t just a spin-off of the BSC: it’s a culturally-shifted mashup of (at least) the two biggest girls’ series of the 90s, not just the BSC but Sweet Valley as well. Of the two series, Sweet Valley is the one that more obviously needs an overhaul to be appropriate for Orthodox Jewish readers. Even my mother, who was not usually very censorious, did not approve of me reading the Sweet Valley High books, which feature a pair of rich, blonde, beautiful California twins in a classic good-twin/bad-twin setup. There’s lots of mildly steamy romance, some adolescent drinking, sexual assault, car crashes, amnesia, and just about every other soap opera trope you can think of – and every book ended with a cliffhanger of some sort. I found them tedious, especially in their kid-friendly formulations, Sweet Valley Twins and Sweet Valley Kids, whose age-appropriate drama lacked the titillation of Sweet Valley High.

Let me introduce you to the initial staff of the BY Times, as I, a non-Jewish childhood reader of 90’s girls books, experienced them:

Shani Baum: clearly identifiable as “the Kristy”: she’s short, loud, bossy, and started the newspaper.

Raizy Segal: a genius like Janine, but shy like Mary Anne

Batya Ben-Levi: an only child like Mary Anne, who wishes she had more siblings

Nechama Orenstein: Like Mallory, a redhead and the youngest in a big family, but she doesn’t like reading, is bad at school, and is generally wild and irresponsible

Chani Kaufman: honestly, it took me a lot of books to realize she was a separate character from Shani. Her distinctive feature, such as it is, is that she’s extremely short.

Pinky & Chinky Chinn: (yes, you read that right) are the rich twins. It wouldn’t do to have a “good” and “bad” twin, so instead we get a Claudia-type as the foil to a responsible, organized twin (much like Elizabeth, the “good” twin in Sweet Valley.) Pinky, the Claudia-type, is really into fashion and design, and also likes eating caramels constantly. Unlike Claudia, whose complexion and figure are unaffected by her sweet tooth, there’s a whole book about fat-shaming Pinky for weighing a couple pounds more than Chinky.

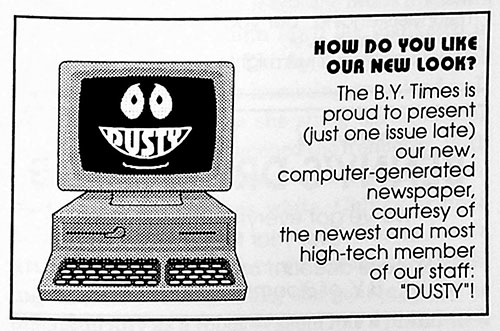

I found these girls’ adventures to be fascinating and strange. Where the Baby-Sitters Club books are written in a way that now reads as “timeless”, that’s also another way to say that it’s disconnected from the time, place, and sociopolitical context in which it was written. In a talk we gave last year, Data-Sitter Maria Sachiko Cecire mused over how we could explore the ways in which the Baby-Sitters Club forms a sort of “small world” (as J.M. Barrie describes a “map of a child’s mind, which is not only confused, but keeps going round all the time”) that captures some things about the adult world (like capitalism and divorce and bra shopping and British palace guards) but leaves out others (collapse of the USSR, the Persian Gulf War, computer viruses, etc.) The BY Times offers a point of contrast where the author made a different set of choices about what made it into her narrative “small world”. On one hand, the characters live in an insular community with a specific set of rules: no one’s eating a bacon cheeseburger or wearing tie-dye leggings with overall shorts. But on another hand, no member of the Baby-Sitters Club learns how to correctly put on a gas mask, or survives a scud missile attack, or helps “Russian” Jewish refugees from Kyiv resettle in the US, or picks up the pieces when the club’s computer is infected with a virus.

I really wanted to do something to explore the scope and nature of the worldbuilding between the BY Times and the Baby-Sitters Club, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine blew up the small world of multilingual and feminist DH projects that I’d created for myself at work, and tackling something that big felt out of reach. Dainy and I had talked about “how Jewish” vs “how American” these books were, but that also meant some hard decisions about how to model each of those things. I wanted something more straightforward, something that I could use to try out a new-to-me text analysis technique.

And I finally found it in the 9th BY Times book, Here We Go Again, which prominently features a new character: a blonde health-food fanatic who’s just moved to town from California.

Sound familiar?

Ilana the California Girl#

With many BY Times characters, you can only see the shadows and contours of influence from the Baby-Sitters Club. Not so with Ilana Silver. Ilana is Dawn with valley girl stereotypes turned up all the way. (Also: Ilana is a really hard name to reliably OCR in the font they used to print BY Times books. She’s “Hana”, “Dana”, “Tiana”, or even “Bana” as often as “Ilana”.)

DSC 17: Cadence’s Archives Mystery covers Junior Data-Sitter Cadence Cordell’s trip to visit the Ann M. Martin Papers at Smith College, but one major finding was a repeated, explicit concern about Dawn and California stereotypes. At the top of the notes for BSC #23: Dawn on the Coast, Martin wrote “No stereotyping CA kids”. In the folder for that same book, it notes that she had already received complaints about Dawn fitting the California stereotype of “blond-haired, blue-eyed, laidback, vegetarian health-nuts”. It comes up again in Super Special #11: Here Come the Bridesmaids!, via Martin’s wanting Carol and Mr. Schafer’s wedding to “seem traditional without smacking of California stereotypes”.

Suffice it to say that Miriam Stark Zakon had no such qualms – either about her depiction of Ilana, or how the other characters interpreted her mannerisms. Ilana gets introduced as the cliffhanger of BYT #8: Summer Daze, when Chani struggles to describe the new arrival from California who had been attending her summer camp:

What could she write? Ilana was… was so… so…

No, she couldn’t really describe her. Not without risking lashon hara[1], that was for sure.

And so the book concludes:

Why is Ilana Silver so indescribable? … Read all about it in the next edition of The B.Y. Times.

Ilana’s first appearance doesn’t come until about ⅓ of the way through book 9, where she makes quite the debut after failing to show up to the first BY Times meeting:

“I’m super sorry, really,” Ilana said earnestly. “I was talking to this really amazing girl and she told me the most amazing things about her grandmother’s life. It was just so exciting! I hope I didn’t miss much at the meeting.” She flashed a sparkling smile at Nechama before pulling out a brown paper bag. Ilana held it out invitingly. “Sprouts, anyone?” she offered.

[…]

“Sprouts, huh?” [Chani] said loudly. “They’re from your mother’s health-food store, aren’t they?”

“That’s right,” Ilana beamed. “It’s the first kosher health-food store in Bloomfield! It totally blows my mind that you’ve managed without one until now.”

“Oh, we got by somehow,” said Chani with a smile as she mentally rolled her eyes. “Still, it’s so nice that we have one now!”

“For sure,” said Ilana placidly, smiling brightly at the two girls. “I mean, like, there’s so much delicious food that’s healthy, too! It’s really much better for people to eat this way—and it’s better for the whole planet, too.” Ilana tossed a lock of blond hair over her shoulder.

The BY Times gets a free computer, and all the girls struggle to use it except for Ilana. As Chani puts it, “Ilana comes from California, and everyone probably has computers there. It’s no crime to know less than she does.”

The book concludes with a surprise birthday party catered by Ilana’s family’s kosher health-food store, where even Ilana’s mother makes fun of her manner of speech: “No problem,” said Mrs. Silver with a smile. “As my daughter would say”—she ruffled Ilana’s blond hair fondly—“It’s, like, no problem at all!”

Amazing! We, like, totally found something that we could measure: how distinctive was Ilana’s speech, compared to Dawn’s?

Dialogue to Data#

How do we figure out if something is, like, totally distinctive? We test to see if you can reliably tell it apart from the thing you’re comparing it to. There’s lots of ways to do that, and not all of them involve computers. But all of them do involve turning the things you want to compare into something that looks like data. Even if you wanted a human (instead of a computer) to evaluate Ilana vs. non-Ilana quotes to see if they can reliably tell them apart, you couldn’t just hand that person a BY Times book, or even a BY Times book that you’ve covered with sticky notes pointing to relevant sections of dialogue. For starters, it’d be hard for them to avoid seeing text like “said Ilana” or “Chani exclaimed” that would give away the answer! What you need to do is take the quotes out of their narrative context and put them into something like a spreadsheet where you can view the quote by itself, but also connect it to metadata like speaker (Ilana/non-Ilana) and source (which book).

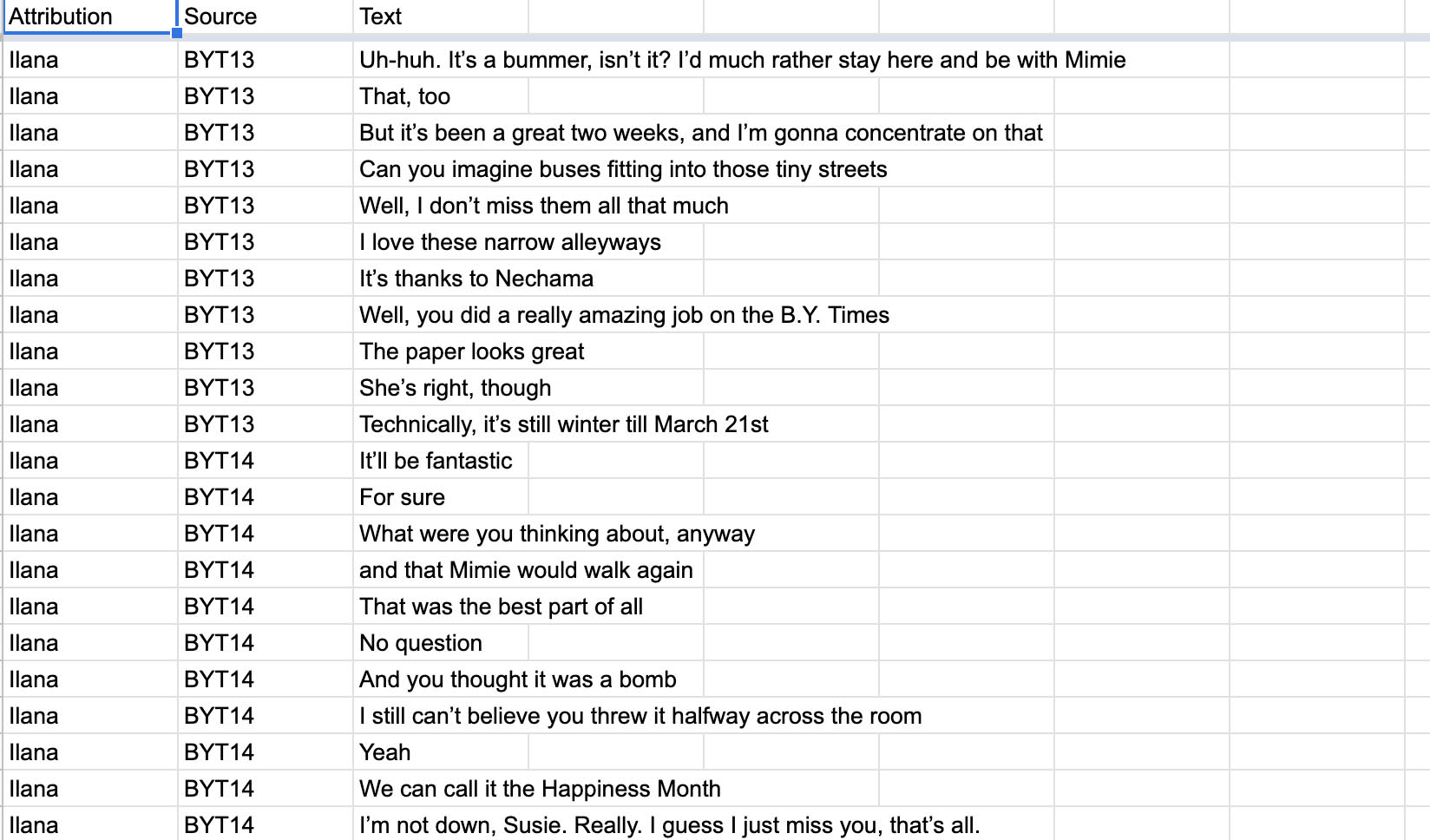

It may come as a surprise that automatic quote extraction and attribution is a pretty difficult computational task. There are systems that try to do it (like David Bamman’s BookNLP, and I was thinking of trying it out when Dainy suggested a classic alternative that would almost certainly be more accurate: ey offered to read through the books and add all the Ilana quotes to a spreadsheet. 🥳 Usually I’d have protested more – let’s leave this to the computers, they’re imperfect but close enough! But I realized that we weren’t going to have a ton of data, since Ilana only appears in books 9-17. And a big part of what makes some degree of computer-error okay is scale: 10 mis-attributions are a much bigger problem if you have 100 examples than if you have 1,000, and by the time you get to 10,000 examples, I’d expect human labor to produce at least that many mistakes. So I took Dainy up on the offer, and ey found 673 instances of Ilana-speech and added them to the spreadsheet.

The process for finding non-Ilana quotes was much less precise. I wasn’t trying to find every quote, and I definitely wasn’t trying to figure out quote attribution. I just wanted stuff that non-Ilana characters said. So I wrote some code to go through the books and pull out everything between quotation marks.

#Importing this to navigate directories

import os

#This lets us use regular expression syntax

import re

#This lets us randomly sample from things

import random

#Specifies the folder where my book text files are

filedirectory = '/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/dsc_byt'

#Changes to that folder

os.chdir(filedirectory)

#For each file in our directory of text files

for file in os.listdir(filedirectory):

#If the file ends with .txt

if file.endswith('.txt'):

#Open the source file

with open(file, 'r') as sourcebook:

#Read the source file

text = sourcebook.read()

#Find all things between quotes

quotes = re.findall(r'“(.*?)”', text)

#Randomly samples our list of quotes for 300 quotes

randomquotes = random.sample(quotes, 300)

#Opens our output file

with open('/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/nonilana.csv', 'w') as out:

#For each quote in our random sample

for randomquote in randomquotes:

#Write it to the output file

out.write(randomquote + '\n')

The problem is, that will get us Ilana quotes along with non-Ilana quotes. But thankfully, we have Dainy’s comprehensive list of Ilana quotes and can use that to remove the Ilana quotes. There’s a catch, though: it will also remove any non-Ilana quotes that are identical to Ilana quotes – thereby increasing the distinctiveness of the two sets, because anything said by both Ilana and non-Ilana characters will only appear in the Ilana data set. In this corpus, that’s only likely to happen with very short quotes, like “Oh?” and “Yes” so we’re going to say it’s not a big deal. But in other corpora, it might be a bigger problem: imagine you’re looking at Star Wars novels to compare Luke Skywalker’s speech vs. other characters. You could accidentally end up modifying your data in such a way that it looks like Luke is the only person who ever says “May the Force be with you.” Collecting your data in a way where you won’t run into this issue is harder, and would involve across-the-board quote attribution. That’s why it really helps to know your data, or work with someone who does – and why there’s no one-size-fits-all workflow for most text analysis stuff. Depending on the particularities of your data, you may be able to take shortcuts that will cut down on labor or complicated algorithms, like we’ve done here.

Dawn’s Dialogue#

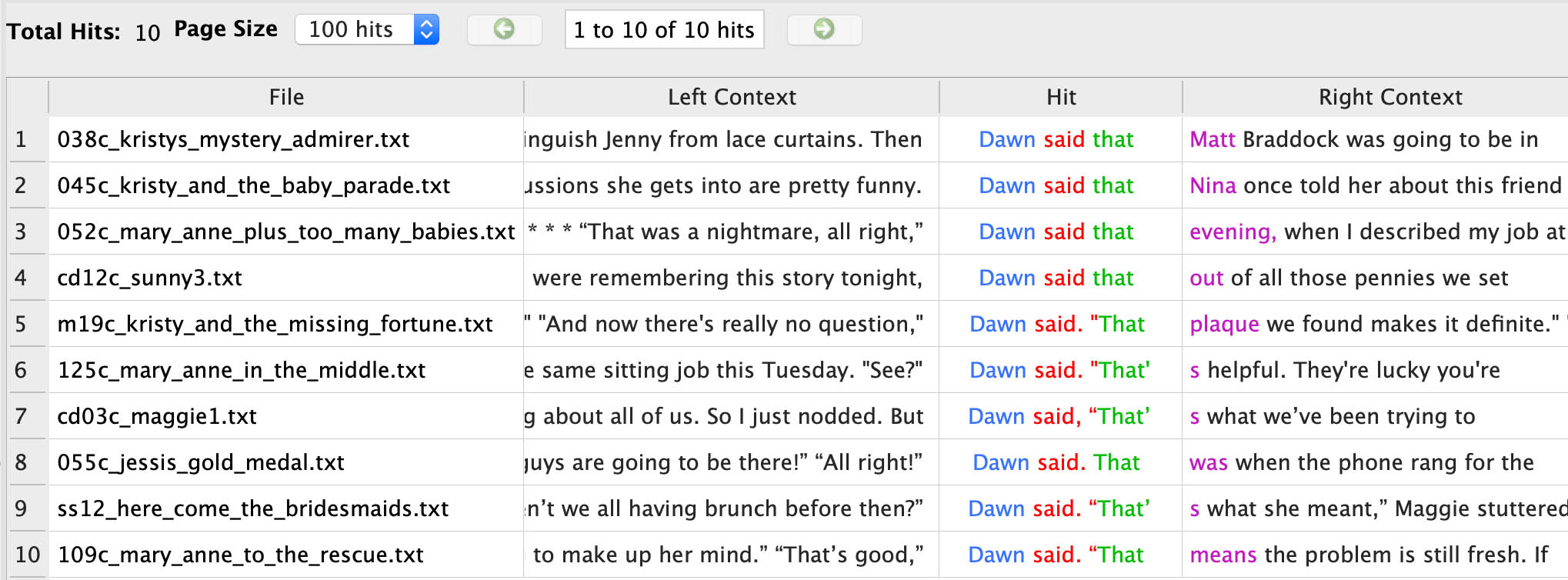

Unlike with Ilana, there’s no shortage of Dawn dialogue – even though she, similarly, shows up after the first book and doesn’t stick around until the end of the series. We’re not trying to comprehensively get all of Dawn’s dialogue, just a quantity similar to what we have for Ilana. We don’t have any particular reason to think that the way Dawn’s dialogue is tagged (e.g. “said Dawn” / “Dawn said” vs. “Dawn exclaimed” vs. Dawn dialogue that isn’t explicitly labeled with her name) has anything to do with the Dawn-ness of the dialogue – though that is something we could test if we felt so inclined. (The BY Times books sometimes use “drawled” with Ilana’s speech.) So I wrote some code to look for any line (i.e. paragraph) in any Baby-Sitters Club book that included “said Dawn” or “Dawn said”, then extracted only the text within quotation marks from those lines.

#File directory for BSC books

filedirectory = '/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/dsc_corpus_clean'

os.chdir(filedirectory)

#Create a list for Dawn quotes

dawnlines = []

#For each file in the file directory

for file in os.listdir(filedirectory):

#If it ends with .txt

if file.endswith('.txt'):

#Open the text file

with open(file, 'r') as book:

#Read in each line into a list

lines = book.readlines()

#For each line

for line in lines:

#If it includes 'said Dawn'

if 'said Dawn' in line:

#Add it to the list

dawnlines.append(line)

#If it includes 'Dawn said'

if 'Dawn said' in line:

#Add it to the list

dawnlines.append(line)

#Print how many Dawn lines we have

len(dawnlines)

1019

#Make a new list for just the Dawn quotes

dawnwords = []

#For each line we pulled out

for dawnline in dawnlines:

#Get the part between quotation marks

dawnquotes = re.findall(r'“(.*?)”', dawnline)

#Fore each quote

for dawnquote in dawnquotes:

#Add it to the list

dawnwords.append(dawnquote)

#Randomly samples our list of Dawn quotes for 300 quotes

randomdawns = random.sample(dawnwords, 300)

#Opens our output file

with open('/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/dawn.csv', 'w') as dawnout:

#For each quote in our random sample

for randomdawn in randomdawns:

#Write it to the output file

dawnout.write(randomdawn + '\n')

This is, once again, a hack for quote attribution and it could backfire, for instance, if Mary Anne said, “I heard that Dawn said I was a bad step-sister.” Thanks to AntConc, we can double-check to make sure there aren’t any examples like that:

Or we could check the text we get once we extract only the things in quotation marks and remove anything that includes the words “Dawn” (since Dawn doesn’t ever talk about herself in the third person).

Non-Dawn dialogue is also easier with the Baby-Sitters Club books. Again, we don’t need all non-Dawn dialogue, we just need a comparably-sized sample. Thanks to the narrative structure of the Baby-Sitters Club, any book with “Dawn” in the title is narrated by Dawn, which means she’s less likely to be speaking, and any tagged speech will use the pronoun “I”. There’s the possibility of some non-tagged Dawn speech (where she says something in quotation marks, but it isn’t labeled as such) getting through, but that’s an edge case that we won’t worry about too much.

Do You See Anything Weird Here?#

When you’re doing computational text analysis, following along with a tutorial or workflow you’ve found online, it’s easy to forget about one of the most important steps that you’ll almost never see written out. That major lifehack, one-weird-trick step is something I like to call “do you see anything weird here?” And sometimes you might not be the right person to do this step – you may need to call in your collaborator with the relevant disciplinary or language expertise. For this project, if something had changed with how Ilana was using Hebrew words, I wouldn’t notice it but Dainy would. But as luck would have it, there was something in the data that was obviously weird to even me: Ilana suddenly and completely drops her “California girl” speech habits in books 13-17. You could be generous and say that it’s a sign she’s adapted to her environment… but it’s harder to believe it would happen so suddenly and completely.

It’s worth running the “do you see anything weird here” check often as you work on a text analysis project – and not every weird thing means you need to make a change! But don’t brush off your skepticism: even if you decide to carry on despite some weirdness, remember that you had questions. Those doubts might be helpful when you reach the point where you need to interpret the results.

In this case, it was clear that we needed to change the plan. We couldn’t use all 674 Ilana speech acts – the Ilana of the early books speaks noticeably differently than the Ilana of the later books. The “California girl” Ilana from books 9-12 only said 230 things according to Dainy’s list, so that’s all we had to work with. I brought this small data set, and a random sample of 230 non-Ilana quotes, to Associate Data-Sitter Mark Algee-Hewitt, to see what he’d suggest.

Length and Normal Distribution#

“Okay, I have all the Ilana quotes and non-Ilana quotes … now what?” I asked.

Mark pulled out his laptop and opened up RStudio. “Before we do anything about Ilana as such, we need to check to make sure any length differences between the samples aren’t significant.”

I looked at Mark quizzically. “I mean… it’s not like there’s a character who’s super into speechifying or anything. And definitely not in the sample we generated. Why do we think length is going to be a problem?”

Mark laughed. “Okay, so this is one of those things that happens at DH conferences – where, like, you’ll walk into a room and we’ll be playing with the BSC corpus, looking for ways to see if Ilana’s dialogue is different than other dialogue, and some bearded guy with a scarf will say, ‘excuse me, did you test for statistical significance in the difference in speech length, and did you assume a normal distribution?’ And everyone’s going to hate him, but he’s not wrong.”

I knew the type, and appreciated the value of preemptively heading off the bearded scarf-wearing guy type. I was in.

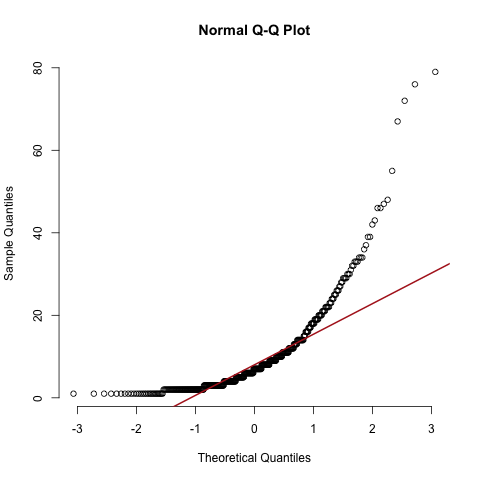

“First, we need to run qqnorm to test for normality. We need to know if it has a normal distribution before we can use a t-test to make sure that differences in length aren’t significant,” said Mark.

Mark opened RStudio, and imported the data Dainy and I had prepared for Ilana and non-Ilana quotes.

Mark mostly codes in R; I mostly work in Python, and the Data-Sitters Club is published as a Jupyter Book using a Python kernel – the thing that interprets and executes the code. So like we discussed in DSC 10, I have to put %%R at the top of each cell of R code that I want to be interpreted as R, rather than Python. If you’re just running R, you don’t need that part.

#This installs rpy2, which is my Python-to-R adapter

import sys

!{sys.executable} -m pip install rpy2

#This loads the Jupyter Notebook extension that lets me

#run R code in a notebook that's otherwise Python by default

%load_ext rpy2.ipython

length.nonilana.table<-length.nonilana[sample(nrow(length.nonilana), 230),]

%%R

#Sets the working directory (e.g. where it looks for files)

setwd("/Users/qad/Documents/GitHub/dsc15")

#Reads the non-Ilana quotes CSV

length.nonilana<-read.csv(file='non_ilana_sample.csv', header=T)

#Reads the Ilana quotes CSV

length.ilana<-read.csv(file='ilana.csv', header=T)

#Sets the column names on the Ilana quotes to be attribution, source, quote

colnames(length.ilana)<-c("Attribution", "Source", "Quote")

#Checks the dimensions (rows, columns) for the non-Ilana quotes

dim(length.nonilana)

[1]

230

2

“Let’s limit the Ilana quotes to the ones in the books where she has the distinctive speech,” said Mark. “Once we do that, we can also drop the source column.”

%%R

#Book source for the quotes is in the second column in this data

#This code only keeps quotes where the source is one of the books

length.ilana.table<-length.ilana[which(length.ilana[,2] %in% c("BYT9", "BYT10", "BYT11", "BYT12")),]

#Keep only the first column (attribution, i.e. "Ilana") and third (the text)

length.ilana.table<-length.ilana.table[,c(1,3)]

#Create a table with the non-Ilana quotes

length.nonilana.table<-length.nonilana

#Rename the columns of the Ilana table to match the non-Ilana table

colnames(length.ilana.table)<-colnames(length.nonilana.table)

#Check the dimensions of the Ilana table

dim(length.ilana.table)

[1]

230

2

“Now, let’s create a table that combines both the Ilana and the non-Ilana quotes.”

%%R

length.final.table<-rbind(length.ilana.table, length.nonilana.table)

dim(length.final.table)

[1]

460

2

“There’s a cleaning function I always use,” said Mark. “It lower-cases the text, and removes punctuation and such. Since we’ll be using that when we look for distinctive words, let’s do that here before we look for the length; it can make a small difference in the word count.”

“Oh, like how ‘Baby-Sitters Club’ could be two or three words, depending on your code?”

“Exactly.”

%%R

#Mark's cleaning function

fullClean<-function(raw.text){

raw.text<-unlist(strsplit(raw.text, ""))

raw.text<-tolower(raw.text)

clean.text<-raw.text[which(raw.text %in% c(letters, LETTERS, " "))]

clean.text<-paste(clean.text, collapse="")

return(clean.text)

}

#Clean the Ilana quotes

clean.length.ilana<-lapply(length.ilana.table$Text, function(x) fullClean(x))

#Clean the non-Ilana quotes

clean.length.nonilana<-lapply(length.nonilana.table$Text, function(x) fullClean(x))

#Adds a CleanText column to the Ilana table

length.ilana.table$CleanText<-clean.length.ilana

#Adds a CleanText column to the non-Ilana table

length.nonilana.table$CleanText<-clean.length.nonilana

#Counts the length and adds a Length column to the Ilana table

text.length<-unlist(lapply(clean.length.ilana, function(x) length(unlist(strsplit(x, " ")))))

length.ilana.table$Length<-text.length

#Counts the length and adds a Length column to the non-Ilana table

text.length<-unlist(lapply(clean.length.nonilana, function(x) length(unlist(strsplit(x, " ")))))

length.nonilana.table$Length<-text.length

“Let’s look at the mean length of the Ilana and non-Ilana quotes.”

%%R

#Average (mean) length of Ilana quotes

mean(length.ilana.table$Length)

[1]

9.095652

%%R

#Average (mean) length of non-Ilana quotes

mean(length.nonilana.table$Length)

[1]

11.13913

“Now we’ll put all this data together in a single table.”

%%R

#Combine Ilana and non-Ilana tables in a single table

length.table<-rbind(length.ilana.table, length.nonilana.table)

dim(length.table)

[1]

460

4

“Let’s check the mean of all the data together.”

%%R

mean(length.table$Length)

[1]

10.11739

“We know that the average length of the Ilana quotes is 9.1 words, and the average for non-Ilana quotes is 11.1 words. What we want to do is compare them, check on whether there’s a meaningful difference between them. The statistical method we’d usually reach for is a t-test – also known as the student’s t-test – which is a statistical test of whether or not the difference in the means of two distributions is significant. We compare the output to an alpha, which is a threshold value used to judge whether a test statistic is statistically significant. By convention, we use .05 – if it’s less than or equal to .05, we say it’s statistically significant. But there’s a catch: the t-test only works if the data is distributed normally – normally in the statistical sense, where most of the values cluster in the central region, and they trail off equally in both directions. A normal distribution looks like a bell curve if you were to visualize it. For this data, that would mean that there’d be (roughly equally) few very long and very short quotes, and most of the quotes would be middle-length.”

“How do we figure that out?” I asked. “There’s got to be a better way than making a chart and eyeballing it, right?”

“Yes,” said Mark. “We can use what’s called a quantile-quantile plot, or qqplot, which is available as an R package. What it does is take two sets of data, and plots each quantile of one data set against the same quantile of the second data set. A quantile is just a way to break up data into chunks with the same probability – you might have heard of quartiles, which break data into four pieces with equal probability: the second quartile is the median of the data, the first quartile is halfway between the starting point and the median, so that 25% of the data is below that point. The third quartile is the middle value between the median and the highest value, so that 75% of the data is below the third quartile. Anyhow, if the data follows a normal distribution, all the points should roughly fall along the reference line.”

%%R

#Creates the qqnorm plot

qqnorm(length.table$Length, pch=1, frame=F)

#Adds the reference line

qqline(length.table$Length, col="firebrick", lwd=2)

“It’s not normal. Look how not-normal it is!” Mark exclaimed. “This data is wonky at the ends – especially the long end. So we have some kind of funky-tail distribution. It’s not normal enough to do a t-test… which means, we have to use a… you know …” Mark gestured vaguely.

“Nope, definitely don’t know.”

It was gratifying to see Mark pull up a web browser and Google for the answer, the same way I do. “Test difference non-parametric data…” and then, scrutinizing the results, he added “in R”. Success, apparently! “That’s it – there’s Mann-Whitney U test, also known as Wilcoxon rank-sum test, two names for, in our case, effectively the same thing – they both allow us to test for the difference between two samples of non-parametric, or non-normal, data. Instead of using mean values like we would use in a t-test, the Mann-Whitney asks: if we choose two random data points from sample A (Ilana) and sample B (non-Ilana), is the probability that A>B equal to the probability that B>A? This is for independent variables – if we had dependent variables, then we could use a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test.”

“Wait a minute, I’m confused again,” I said. “If I’m remembering right, ‘independent’ variables are things that you change in an experiment like this, and ‘dependent’ variables are things that change as a result of how you’ve changed the independent variable. Why are we saying we’re looking at independent variables? Couldn’t we argue that length is a dependent variable resulting from the independent variable of Ilana vs. non-Ilana?”

“Yes, the length of both Ilana and non-Ilana quotes are dependent on who’s speaking them – that’s exactly the point of what we’re looking at,” said Mark. “But the question here is: are they dependent on each other? Does having short Ilana quotes mean that the length of the non-Ilana quotes will be affected, or vice-versa? Maybe if we knew the author had a very strict word-count limit or something, but the answer there is no, so we don’t have to worry about dependence.”

“When would you have to worry about it?” I angsted.

“Imagine if we had a data set where one feature is the number of times the word ‘a’ appeared in English-language texts, and another feature is the number of articles from a part-of-speech parse. Since increasing one increases the other, that means they are dependent.”

“That makes sense” I said, relieved.

Mark closed his browser and opened RStudio. “What we want to do is regress length onto attribution – a regression analysis helps us measure the influence of one or more independent variables – attribution, in this case – on a dependent variable, length.”

%%R

w.result<-wilcox.test(Length~Attribution, length.table)

w.result

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data:

Length by Attribution

W = 24564, p-value = 0.1849

alternative hypothesis:

true

location shift

is

not equal to

0

“The p-value is .14, so we can safely say that the fact that non-Ilana dialogue is slightly longer (11.1 vs 9.1 for Ilana dialogue) shouldn’t make a difference,” Mark concluded. “Length has a large effect – in fact, it tends to have an outsized effect on computational results. You can adjust for length, but it’s kind of difficult. So when you’re comparing two groups of things, if there’s a statistically significant difference in length between them, it’s probably going to have an effect and we don’t want it to. We don’t want to create a model that just says “not-Ilana dialogue is longer, so if it’s long, it’s not Ilana.” That’s not going to get us a kind of classification that helps answer our question. Sometimes it can be very accurate – for the LitLab’s short story project, we created a model that predicted with 100% accuracy whether something was a short story or a novel, because it turns out that short stories are shorter than novels. It was extremely accurate, but completely unhelpful. In this case, it’s important that we know whether or not there’s a significant difference in length, because that’s not a difference we’re interested in. Hopefully there are other differences that we are interested in. Sometimes length could end up being an interesting difference – if the p-value was low for that test, that could be a sign that her dialogue is shorter in a way that merits a second look. It’s not, but now we know that conclusively, and we can discount it as a potentially confounding factor.”

Distinctive words#

Mark pulled out some more code. “Let’s look for some distinctive words. We’ll start by installing some R packages…”

%%R

setwd("/Users/qad/Documents/GitHub/dsc15")

if(!require(tm)){

install.packages("tm")

}

if(!require(MASS)){

install.packages("MASS")

}

if(!require(klaR)){

install.packages("klaR")

}

if(!require(e1071)){

install.packages("e1071")

}

if(!require(SnowballC)){

install.packages("SnowballC")

}

if(!require(neuralnet)){

install.packages("neuralnet")

}

Loading required package: tm

Loading required package: NLP

Loading required package: MASS

Loading required package: klaR

Loading required package: e1071

Loading required package: SnowballC

Loading required package: neuralnet

“Now, we’re going to import the data and make sure it looks right.”

%%R

#Import non-Ilana sample

non.ilana.mdws<-read.csv(file='non_ilana_sample.csv', header=T)

#Import Ilana quotes

ilana.mdws<-read.csv(file='ilana.csv', header=T)

#Label the columns for the Ilana quotes

colnames(ilana.mdws)<-c("Attribution", "Group", "Text")

#Get the dimensions of the non-Ilana data

dim(non.ilana.mdws)

[1]

230

2

%%R

#Get the dimensions of the Ilana data

dim(ilana.mdws)

[1]

673

3

“So far, so good,” said Mark. “Let’s make sure we’re seeing the right number for the different books with Ilana quotes.”

%%R

#Get Ilana quotes, grouped by book

table(ilana.mdws$Group)

BYT10

BYT11

BYT12

BYT13

BYT14

BYT15

BYT16

BYT17

BYT9

36

100

38

126

108

64

88

57

56

“Now, we need to limit our Ilana quotes to just those books where she has the distinctive speech patterns.”

%%R

#Use only the Ilana quotes from books 9-12

ilana.quotes.mdws<-ilana.mdws$Text[which(ilana.mdws$Group %in% c('BYT9', 'BYT10', "BYT11", "BYT12"))]

#Get the length of the Ilana quotes from the distinctive books

length(ilana.quotes.mdws)

[1]

230

“We’ve already imported the same sample as before for the non-Ilana quotes, so we have the same number as the Ilana quotes. Now, we’ll put all the quotes together into a single R vector.”

%%R

#Create a vector of just the text of non-Ilana quotes

non.ilana.quotes.mdws<-non.ilana.mdws$Text

#Combine Ilana and non-Ilana quotes

quotes.mdws<-c(ilana.quotes.mdws, non.ilana.quotes.mdws)

length(quotes.mdws)

[1]

460

%%R

#Create a vector for groups, to label Ilana & non-Ilana data

groups.mdws<-c(rep("Ilana", 230), rep("nonIlana", 230))

length(groups.mdws)

[1]

460

“Finally, we’ll create a new table out of the corpus of quotes and the group designations.”

%%R

#make a new table out of the sampled corpus and group designations

new.ilana.table.mdws<-data.frame(groups.mdws, quotes.mdws)

metadata.table.mdws<-new.ilana.table.mdws

“Let’s clean our quotes next! We should also check to see if the default English stopwords list includes any of the ‘Ilana words’.”

%%R

#Extract the text from the table

raw.corpus.mdws<-quotes.mdws

#Apply the cleaning function

clean.corpus.mdws<-lapply(raw.corpus.mdws, function(x) fullClean(x))

#Create a vector with the clean corpus

clean.corpus.mdws<-Corpus(VectorSource(clean.corpus.mdws))

#Remove stopwords

clean.corpus.mdws<-tm_map(clean.corpus.mdws, content_transformer(removeWords), stopwords("en"))

#Create a vector with the default English stopwords list

all.sw<-stopwords('en')

In addition: Warning message:

In tm_map.SimpleCorpus(clean.corpus.mdws, content_transformer(removeWords), :

transformation drops documents

Mark skimmed the list, then frowned. “Let’s double-check that the major ‘Ilana words’ aren’t going to get caught in our stopwords list. We can search for them like this.”

%%R

which(all.sw=="like")

integer(0)

%%R

which(all.sw=="really")

integer(0)

“That means those words aren’t there,” said Mark. “Compared to this, if we pick a word that is on the list:”

%%R

which(all.sw=="has")

[1]

47

“This shows that ‘has’ is the 47th word on the stopword list. All right, it’s good to know we won’t be dropping all the Ilana-specific words. Next, let’s make a document-term matrix.”

%%R

corpus.dtm.mdws<-DocumentTermMatrix(clean.corpus.mdws, control=list(wordLengths=c(1,Inf)))

corpus.dtm.mdws

<<DocumentTermMatrix (documents: 460, terms: 988)>>

Non-/sparse entries: 2408/452072

Sparsity : 99%

Maximal term length: 19

Weighting : term frequency (tf)

“Let’s see if we have any quotes that just get deleted entirely once we remove stopwords.”

%%R

#Get the document-term matrix as a matrix

corpus.matrix.mdws<-as.matrix(corpus.dtm.mdws)

#Add up the word counts for each row (quote)

all.sums.mdws<-rowSums(corpus.matrix.mdws)

#Which ones have a total word count of zero (i.e. no words)

length(all.sums.mdws==0)

[1]

460

“Hmm… what were those quotes before they got deleted?”

%%R

raw.corpus.mdws[which(all.sums.mdws==0)]

[1]

"I was here before"

"This is it"

"There she is"

[4]

"So do I."

"What is it?"

"If you have to,"

[7]

"Why is that?"

"No..."

"Not me,"

[10]

"What?"

"No,"

"You what?!"

“Okay, we can live with that. Let’s remake our corpus matrix with only those quotes that don’t get deleted by the stopwords.”

%%R

corpus.matrix.mdws<-as.matrix(corpus.dtm.mdws)

corpus.matrix.mdws<-corpus.matrix.mdws[-which(all.sums.mdws==0),]

dim(corpus.matrix.mdws)

[1]

448

988

“And update our metadata table to remove the metadata for quotes that would be deleted by the stopwords.”

%%R

metadata.table.mdws<-metadata.table.mdws[-which(all.sums.mdws==0),]

dim(metadata.table.mdws)

[1]

448

2

“Now that we have that in order, we’re going to look for the 500 most frequent words, and sort them in descending order.”

%%R

n=500

word.sums.mdws<-colSums(corpus.matrix.mdws)

word.sums.mdws<-sort(word.sums.mdws, decreasing=T)

mfw.mdws<-names(word.sums.mdws[1:n])

mfw.mdws[1:15]

[1]

"like"

"just"

"im"

"right"

"thats"

"can"

"sure"

[8]

"well"

"get"

"good"

"think"

"really"

"dont"

"amazing"

[15]

"now"

“Oh yeah, those top most-frequent words are VERY Ilana,” I said, looking at the list.

“Let’s run the most distinctive word code that we usually use around the Lab,” said Mark. “We’ll use 0.05 as the cut-off – the usual threshold for statistical significance – though sometimes we use something much smaller to find highly distinctive words.”

“How does that code work?” I asked.

“Basically, we give it a vector of groups – in this case, we’ve got Ilana and Non-Ilana. For each group, we compare the text in that group to all the text in the other groups combined and ask, ‘What if we take the word frequencies in all the other groups as kind of like a default?’ Then we look at what words in the group text occur statistically significantly more frequently than in the other groups put together.”

%%R

#This code is called by the function below - don't run this by itself

#Code takes two variables.

#1. A document term matrix (rows as documents, columns as words, cells as counts of words in documents)

#2. A vector of group assignments for the texts

qdMDWs<-function(dtm.matrix, groups, alpha=0.05){

#let user know what's happening

print("MDWs")

#get all of the actual words from the columns in the document term matrix

all.terms<-colnames(dtm.matrix)

#figure out which columns in the DTM correspond to the target population

target.index<-which(groups=="Target")

#Assuming that there are more than one text in the target group

if(length(target.index)>1){

#get the total count of each word for all of the texts in the target group

target.sub<-colSums(dtm.matrix[target.index,])

#if not

} else {

#just get the counts for that text

target.sub<-dtm.matrix[target.index,]

}

#get the total count for all groups of each words

total.obs<-colSums(dtm.matrix)

#get the total word count for all of the words in the target subset of the corpus

target.words<-sum(target.sub)

#calculate frequencies of words in target group by dividing by total words in corpus

target.scaled<-target.sub/sum(target.sub)

#calculate frequencies of all words in the corpus (target and non-target)

total.scaled<-total.obs/sum(total.obs)

#find expected number of each words in the target sub-corpus by multiplying the total frequency across the entire corpus by the number of words in the target corpus

target.exp<-round((total.scaled*target.words), 0)

#find the difference between the expected number of words and the actual number of words in the target subcorpus

term.diff<-target.sub-target.exp

#find all of the words that show up less frequently than expected

keep.index<-which(term.diff>0)

#remove the words that show up less frequently than expected from the total corpus

all.terms<-all.terms[keep.index]

#remove the words that show up less frequently than expected from the target subcorpus

target.sub<-target.sub[keep.index]

#remove the words that show up less frequently than expected from the target expected subcorpus

target.exp<-target.exp[keep.index]

#find the total number of times for each word that it isn't in the target corpus

target.missing<-target.words-target.sub

#find the total number of times for each expected word that would would expect to not find it in the target corpus

target.missing.exp<-target.words-target.exp

#for every word, create a 2x2 contingency table of the number of times the word appears, the number of times it doesn't appear, the number of times we expect it to appear, the number of times we expect it not to appear

all.c.tables<-mapply(function(x,y,z,a) matrix(c(x,y,z,a), ncol=2, byrow=T), target.sub, target.exp, target.missing, target.missing.exp, SIMPLIFY=F)

#run a fisher's exact test on all of the contingency tables (1 ber word)

all.fishers<-lapply(all.c.tables, function(x) fisher.test(x))

#extract the p value from all of the fisher's tests

all.p<-unlist(lapply(all.fishers, function(x) x$p.value))

#figure out which ones are significantly more present

sig.index<-which(all.p<alpha)

#tell the user you are about to print out the number of significant mdws

print("Significant MDWs:")

#print the number of significant mdws

print(length(sig.index))

#if there are more than 0 mdws

if(length(sig.index)>0){

#create a vector of the words (the mdws)

Term<-all.terms[sig.index]

#create a vector of the number of times each word appears in the target corpus

Obs<-target.sub[sig.index]

#create a vector of the frequency of the words in the target corpus

ObsScaled<-Obs/target.words

#create a vector of the observed over expected for each word

Obs_Exp<-Obs/target.exp[sig.index]

#create a vector of the p.values for each word

pValue<-all.p[sig.index]

#merge all of these vectors into a dataframe

final.table<-data.frame(Term, Obs, ObsScaled, Obs_Exp, pValue)

#sort the data frame by the ObsScaled

final.table<-final.table[order(final.table[,3], decreasing=T),]

#create a column ranking the words by their scaled frequency

final.table$Rank<-seq(1, nrow(final.table), by=1)

#return the table

return(final.table)

} else {

#if there are no mdws, return an NA

return(NA)

}

}

#this is the code to run, it takes two variables

#1) a document term matrix (words as columns, texts as rows, cells as individual counts (NOT FREQUENCIES))

#2) a vector of group assignments for the texts - the code will find MDWs for each group

allMDW<-function(dtm.matrix, group.vector, alpha=0.05){

#find the names of the unique groups

unique.groups<-unique(group.vector)

#find the number of unique groups

num.groups<-length(unique.groups)

#create an empty list to put the mdw tables in

all.mdws<-list()

#for each group

for(i in 1:num.groups){

#get the name of the current group

curr.group<-unique.groups[i]

#print out the name of the current group

print(curr.group)

#move group vector into a temporary variable

temp.groups<-group.vector

#rename all of the elements of that vector that correspond to the current target group as "Target"

temp.groups[which(temp.groups==curr.group)]<-"Target"

#run the code above, but sending the original dtm, by our modified group vector in which the ones we care about are now named "Target"

mdws<-qdMDWs(dtm.matrix, temp.groups, alpha)

#if there are any MDWs

if(!is.na(mdws)){

#On the resulting table from the code above, create a new column labeled by the name of the group

mdws$Group<-rep(curr.group, nrow(mdws))

#add that mdw table (the current one) to the list of all mdw tables

all.mdws<-c(all.mdws, list(mdws))

}

}

#collapse the list of all mdw tables into one big table

all.mdws<-do.call("rbind", all.mdws)

#return it

return(all.mdws)

}

“Okay, let’s run it!” I said.

%%R

#Get the group data from the metadata

group.source.mdws<-metadata.table.mdws$Group

#Run the allMDW function using the corpus, the groups, and a cut-off of 0.5

mdw.table<-allMDW(corpus.matrix.mdws, group.source.mdws, 0.05)

#Create a CSV for the MDWs

write.csv(mdw.table, file="CorpusMDWs.csv", row.names=F)

mdw<-unique(mdw.table[,1])

NULL

[1]

"MDWs"

[1]

"Significant MDWs:"

[1]

0

NULL

[1]

"MDWs"

[1]

"Significant MDWs:"

[1]

0

“Well, it looks like there are no distinctive words in Ilana quotes vs. non-Ilana,” said Mark.

“How can that be?” I asked. “What about ‘totally’, ‘like’, ‘amazing’…?”

“They’re a noticeable part of some of the Ilana quotes, sure, but they’re not so frequent across all the Ilana quotes to be picked up here,” Mark replied. “For fun, let’s double the cut-off, though the higher we raise this number the more dubious our results are as ‘most distinctive words’.”

%%R

group.source.mdws<-metadata.table.mdws$Group

#Now we're using .1 as the cutoff

mdw.table<-allMDW(corpus.matrix.mdws, group.source.mdws, 0.1)

write.csv(mdw.table, file="CorpusMDWs-v2.csv", row.names=F)

mdw<-unique(mdw.table[,1])

NULL

[1]

"MDWs"

[1]

"Significant MDWs:"

[1]

0

NULL

[1]

"MDWs"

[1]

"Significant MDWs:"

[1]

0

Trying PCA#

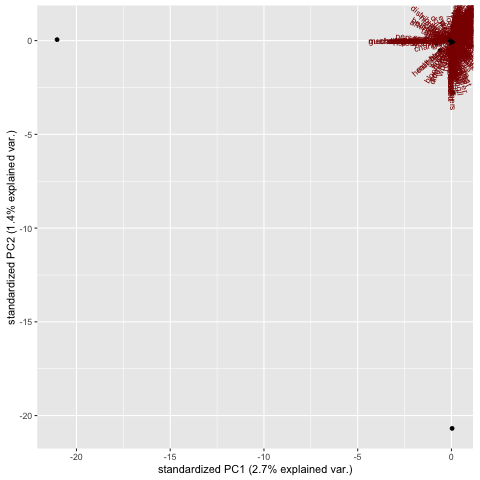

“Okay. Let’s give the most distinctive words a miss. What if we see if there’s any separation using PCA?”

PCA – finally, that was a method I knew something about thanks to Heather Froehlich in DSC 10: Heather Likes Principal Component Analysis. In that book, we used a couple different sets of word frequencies to see how the Baby-Sitters Club books – and other young-reader series books – clustered, in ways connected to author and topic.

“We’re going to scale our corpus for length by turning word counts into word frequencies – dividing each word count by the length of the document. We know that there is not a significant difference between Ilana and non-Ilana quotes, but there ARE some that are shorter. We don’t want our model to just group these together and tell us they’re one thing. So after we scale the corpus, we’ll just keep the most frequent words we identified earlier.”

%%R

#Sets the working directory (e.g. where it looks for files)

setwd("/Users/qad/Documents/GitHub/dsc15")

#Reads the non-Ilana quotes CSV

nonilana.pca<-read.csv(file='non_ilana_sample.csv', header=T)

#Reads the Ilana quotes CSV

ilana.pca<-read.csv(file='ilana.csv', header=T)

#Sets the column names on the Ilana quotes to be attribution, source, quote

colnames(length.ilana)<-c("Attribution", "Source", "Quote")

#Checks the dimensions (rows, columns) for the non-Ilana quotes

dim(length.nonilana)

[1]

230

2

%%R

ilana.quotes.pca<-ilana.mdws$Text[which(ilana.mdws$Group %in% c('BYT9', 'BYT10', "BYT11", "BYT12"))]

%%R

#Turn word counts into word frequencies

scaled.dtm.pca<-corpus.matrix.mdws/rowSums(corpus.matrix.mdws)

#Get the most frequent words using the scaled corpus

features.to.keep.mdws<-mfw.mdws

#Create the feature table

feature.table.pca<-scaled.dtm.pca[,which(colnames(scaled.dtm.pca) %in% features.to.keep.mdws)]

feature.names.pca<-colnames(feature.table.pca)

#Do PCA to see if there is visual separation between the groups based on all 500 most frequent words

colnames(feature.table.pca)<-feature.names.pca

test.pca<-prcomp(feature.table.pca)

#Load the biplot library

library(ggbiplot)

#Generate the biplot

test.pca<-prcomp(feature.table.pca, scale=T)

ggbiplot(test.pca, ellipse=T, groups=metadata.table.mdws$Group)

Loading required package: ggplot2

Attaching package: ‘ggplot2’

The following object is masked from ‘package:NLP’:

annotate

Loading required package: plyr

Loading required package: scales

Loading required package: grid

“Nope. Nope, there is not,” said Mark.

I could see what he meant, thanks to DSC 10 – everything was all lumped together, rather than distributed across all the quadrants, or arranged in nice clumps.

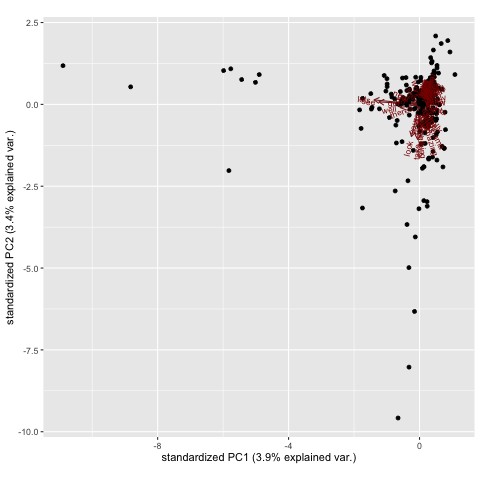

“Maybe the 500 most distinctive words is just too much. Let’s try PCA with just the top 50.”

%%R

#Try again with 50 words

top.mfw.pca<-mfw.mdws[1:50]

top.mfw.pca

[1]

"like"

"just"

"im"

"right"

"thats"

"can"

[7]

"sure"

"well"

"get"

"good"

"think"

"really"

[13]

"dont"

"amazing"

"now"

"totally"

"nechama"

"one"

[19]

"chani"

"going"

"mrs"

"way"

"batya"

"us"

[25]

"will"

"pinky"

"know"

"okay"

"theres"

"come"

[31]

"make"

"new"

"time"

"much"

"lets"

"see"

[37]

"hey"

"shes"

"look"

"got"

"youre"

"want"

[43]

"work"

"go"

"something"

"mean"

"great"

"take"

[49]

"youll"

"shani"

%%R

#Only keep the top 50 features

top.features.pca<-feature.table.pca[,which(colnames(feature.table.pca) %in% top.mfw.pca)]

#Get the actual words

feature.names.pca<-colnames(feature.table.pca)

dim(top.features.pca)

[1]

448

50

“We’ve got the 50 most frequent words occurring in our corpus of 448 quotes,” said Mark. “It’s 448 because we lost some to stopwords. Let’s see if this does any better with PCA.”

%%R

colnames(feature.table.pca)<-feature.names.pca

test2.pca<-prcomp(top.features.pca)

library(ggbiplot)

test2.pca<-prcomp(top.features.pca, scale=T)

ggbiplot(test2.pca, ellipse=T, groups=metadata.table.mdws$Group)

“Hmm… PC1 still only explains about 4% of the variation,” said Mark grimly. “Maybe we’re just looking at too many features. How about if we try a stepwise variable selection to see if we can find a better feature set for classification?”

Stepwise variable selection#

“I was with you on PCA, but you’ve lost me again,” I said.

“Stepwise selection – sometimes it’s called stepwise regression – involves adding and removing predictors – things that you might use to differentiate one group from another – until you get the set of variables that get you the best-performing model.”

“Got it! Let’s see what it gives us!” I exclaimed.

“I’ll set the stop criterion to be an improvement of less than 0.1% – so if it doesn’t improve by that much, it will stop adding and subtracting predictors.”

%%R

setwd("/Users/qad/Documents/GitHub/dsc15")

ilana.sc<-read.csv("ilana.csv", header=T)

non.ilana.sc<-read.csv("non_ilana_sample.csv", header=T)

ilana.quotes.sc<-ilana.sc$Quote[which(ilana.sc$Source %in% c("BYT9", "BYT10", "BYT11", "BYT12"))]

all.text.sc<-c(ilana.quotes.sc, non.ilana.sc$Text)

groups.sc<-c((rep("Ilana", 230)), rep("NonIlana", 230))

%%R

metadata.table.sc<-data.frame(all.text.sc, groups.sc)

colnames(metadata.table.sc)<-c("Text", "Group")

raw.corpus.sc<-all.text.sc

clean.corpus.sc<-lapply(raw.corpus.sc, function(x) fullClean(x))

#Create a vector with the clean corpus

clean.corpus.sc<-Corpus(VectorSource(clean.corpus.sc))

corpus.dtm.sc<-DocumentTermMatrix(clean.corpus.sc, control=list(wordLengths=c(1,Inf)))

corpus.matrix.sc<-as.matrix(corpus.dtm.sc)

corpus.dtm.sc

<<DocumentTermMatrix (documents: 460, terms: 1095)>>

Non-/sparse entries: 4253/499447

Sparsity : 99%

Maximal term length: 19

Weighting : term frequency (tf)

%%R

n=75

word.sums.sc<-colSums(corpus.matrix.sc)

word.sums.sc<-sort(word.sums.sc, decreasing=T)

mfw.sc<-names(word.sums.sc[1:n])

scaled.dtm.sc<-corpus.matrix.sc/rowSums(corpus.matrix.sc)

features.to.keep.sc<-mfw.sc

feature.table.sc<-scaled.dtm.sc[,which(colnames(scaled.dtm.sc) %in% features.to.keep.sc)]

feature.names.sc<-colnames(feature.table.sc)

colnames(feature.table.sc)<-feature.names.sc

dim(feature.table.sc)

[1]

460

75

%%R

library(klaR)

feature.names.sc<-gsub("’", "'", feature.names.sc)

colnames(feature.table.sc)<-feature.names.sc

vars<-stepclass(feature.table.sc, metadata.table.sc$Group, method="lda", improvement=0.0001)

correctness rate: 0.5413; in: "like";

variables (1):

like

correctness rate: 0.57826; in: "amazing";

variables (2):

like,

amazing

correctness rate: 0.6087; in: "right";

variables (3):

like,

amazing,

right

correctness rate: 0.62391; in: "out";

variables (4):

like,

amazing,

right,

out

correctness rate: 0.63696; in: "can";

variables (5):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can

correctness rate: 0.64783; in: "we";

variables (6):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we

correctness rate: 0.65435; in: "okay";

variables (7):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay

correctness rate: 0.66087; in: "totally";

variables (8):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally

correctness rate: 0.66522; in: "sure";

variables (9):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure

correctness rate: 0.67826; in: "chani";

variables (10):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani

correctness rate: 0.68478; in: "us";

variables (11):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us

correctness rate: 0.68696; in: "mrs";

variables (12):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us,

mrs

correctness rate: 0.69348; in: "theres";

variables (13):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us,

mrs,

theres

correctness rate: 0.69565; in: "one";

variables (14):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us,

mrs,

theres,

one

correctness rate: 0.69783; in: "way";

variables (15):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us,

mrs,

theres,

one,

way

correctness rate: 0.7; in: "the";

variables (16):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us,

mrs,

theres,

one,

way,

the

correctness rate: 0.70435; in: "really";

variables (17):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us,

mrs,

theres,

one,

way,

the,

really

correctness rate: 0.71087; in: "make";

variables (18):

like,

amazing,

right,

out,

can,

we,

okay,

totally,

sure,

chani,

us,

mrs,

theres,

one,

way,

the,

really,

make

hr.elapsed

min.elapsed

sec.elapsed

0.000

0.000

41.655

`stepwise classification', using 10-fold cross-validated correctness rate of method lda'.

460 observations of 75 variables in 2 classes; direction: both

stop criterion: improvement less than 0.01%.

“This could be worse,” sighed Mark. “But 70% is still not great. Quotations are hard because they’re very short. We need to find the right feature set,” he concluded. “I’m not feeling it.”

“Is that it?” I asked, a note of despair creeping into the question. “We just can’t tell the difference computationally?”

“Oh no, we’ve only been playing with this for ten minutes,” laughed Mark. “I don’t usually give up this easily.”

Measuring the human success rate#

Mark considered the data for another moment. A little smile crept over his face. “Let’s play a game. I’m going to read you a quote, and you’ll tell me if it’s Ilana or non-Ilana.”

“Same way as yesterday.” - “Not Ilana.”

“Mellow out, Pinky!” - “Maybe?”

“I told you something would come up.” - “Not Ilana.”

“Winter, yuk.” - “Oh, that’s Ilana – New York winters are rough if you’re coming from California.”

“I wish you’d come with us, Pinky.” - “Not Ilana.”

“Could you run down to the grocery and pick up some for me?” - “Not Ilana.”

“What size is your sign going to be?” - “Not Ilana! I remember that part, I’m pretty sure that was something with the twins.”

“Nechama, look! That’s amazing!” - “Definitely Ilana.”

“We have to be able to do things openly.” - “Not Ilana.”

We went on in that fashion for a while.

Mark tallied the results. “So you got 9 right out of 15 – and of the wrong ones, you said that 6 were not Ilana when, in fact, they were. 60% is better than chance, but not by a whole lot – and that’s you who’s read the books and has the knowledge of the plot. The computer won’t have that, so teaching it to do any better than you is going to be tricky.”

That’s a good point to remember when you’re doing this work. Things like narrative context? That’s still pretty much a human-exclusive thing. There are algorithms that “understand” (don’t understand like a human) “context” (a window of words around the word you’re looking at) – things like word vectors, which we’ll cover in a future book. But remembering that something must be a quote from a particular character because of where or how it appeared in a story? That’s a job for squishy human brains.

“There are two classic problems with text analysis here,” mused Mark. “One is that I don’t think we have enough text in our examples. Classifying at the dialogic level is not going to be useful. Or possible!”

“It’s funny,” I said. “Reading these books as a human, the differences in her speech style are really prominent. And the text even brings it up explicitly, through her mother teasing her. But is this one of those cases where it’s just human perception being about more than just frequency?”

“I think you’re right, the things that pop out to us as readers or the characters listening to her are just not frequent enough for a computer,” said Mark. “The fact that you have false negatives is telling. When you saw a ‘California girl sentence’, you recognize it as Ilana, but she’s not saying a lot of sentences all the time. If we take this as a representative sample, you only identified 60% of the Ilana sentences – which means around 40% of the time, what Ilana is saying isn’t a ‘California girl sentence’. Which is not to say she doesn’t have a distinctive discourse…”

Mark pulled up RStudio.

“Based on our stepwise variable selection,” said Mark, “The best three words for differentiating Ilana and non-Ilana are ‘like’, ‘amazing’, and ‘right’. There’s 33 Ilana quotes with ‘like’… and 11 non-Ilana quotes with it.”

“And realistically, those 11 are probably mostly verbs,” I added. “Or maybe prepositions. But no one’s using ‘like’ like Ilana.”

“True,” Mark smiled. “And I know it’s a little uncomfortable, comparing things this way. All we’re doing is looking at the frequency of the word ‘like’, however it’s being used. But there’s something to that: when it’s used as a discourse particle, like Ilana uses it, ‘like’ appears with a different frequency than when it’s used as a verb of preposition. When we see a lot of ‘like’, odds are it’s being used as a discourse particle. Now, if we wanted to be absolutely certain, in theory we have the tools for it: we could use natural-language processing algorithms, like Stanford NLP, to try to parse the syntax of these quotes and identify where ‘like’ is being used as a verb, vs. preposition, vs. discourse particle. But even for English, I don’t think the NLP models are trained on data that would reliably identify the discourse particle usage of ‘like’ – a lot of it is news sources!”

We’d been down this road before, with DSC Multilingual Mystery 2: Beware, Lee and Quinn! The French model struggled to identify and categorize entities in French that it could easily do in English. So it’s a similar problem here, even if it gets further into the nuances of the model than just named entities.

“What all this shows is what I was thinking when I saw this data,” concluded Mark. “Based on words, and trying to classify quotes, Ilana’s discourse is just not distinctive enough across all her utterances. Only 40% of the sentences are ‘California girl sentences’, and that’s it. There are three possibilities here: one, we could try moving on to a classifier that’s better or more precise… but I don’t know how close we’re going to get. If you can’t do it, I don’t think the best neural net is going to do it. Two, we could stop trying to classify sentences and knit this into larger blocks of text. That’d be a little artificial, but if it’s all glued together we’ll see differences in discourse. Three, we try non-word features. Part-of-speech is one option, punctuation is another, and strings of three characters are another one.”

Three-character sequences#

I fixed Mark with a hard stare. “I don’t like that last one. Why would you break up words?”

“It gets you more things to count, especially when you don’t have a lot of text. And three-character sequences have proven to be more reliable than words for forensic analysis in cases where we have very little text.”

“Fine, but… they’re … not … words. Like, we’re getting into English morphology here, but not even rigorously, because you’re going to end up with three-character sequences like ‘ing’ where, okay, that’s a gerund, but you’re going to get other ones that span the root/inflection boundary, and… I DON’T LIKE IT,” I sputtered.

“Words have their downsides, too,” Mark nudged. “Andrew Piper’s been arguing for years that characters aren’t distinctive, that we the readers bring the distinctiveness of characters to the characters. Insofar as stylometry is ‘right’ – which is to say, if ‘style’ is the product of authorial unconscious word usage – it’s impossible for an author to lose their own ‘style’ to the point where characters can assume distinctive voices. So I could write a California girl, but she’s going to sound like the Mark version of a California girl, and the second I write a sentence for her that doesn’t include ‘like’, ‘totally’, or ‘amazing’… then it’s going to sound like me.”

I was very reluctantly willing to try this. We considered the different options together. There was some data we had to throw out because the whole thing was less than three characters (e.g. “Hi”). We decided punctuation might be important here– Ilana likes exclamation marks.

Mark picked up on my ongoing anxiety about this approach. “The way I see it, when we do this kind of work, our questions are guided by humanistic inquiry, but our interpretation should be guided by … results. So, if it works, that means that there’s something that’s happening at a differentiable level. Just because strings of three characters aren’t meaningful for us as readers doesn’t mean they’re not meaningful, period.” Mark continued to type away at the R code. “I still don’t think this is going to work…” he said. “On these things, I sit in a weird place between the scarf-wearing crowd…” – and it’s true, Mark does also have a beard – “… and the people who want results to be human-readable. This is a problem at a deep level, like neural nets that create math proofs that work, but we can’t really trace the path to see how. But I think it’s interesting that there’s something about these things that we don’t see as readers, but is legible at a different level.”

Mark re-imported all the data, limited Ilana’s quotes to the books where she has distinctive dialogue, used the sample of the non-Ilana dialogue, and added it to a new text vector.

%%R

setwd("/Users/qad/Documents/GitHub/dsc15")

ilana.tg<-read.csv("ilana.csv", header=T)

non.ilana.tg<-read.csv("non_ilana_sample.csv", header=T)

non.ilana.tg<-non.ilana.tg[,2]

ilana.quotes.tg<-ilana.tg$Quote[which(ilana.tg$Source %in% c("BYT9", "BYT10", "BYT11", "BYT12"))]

all.text.tg<-c(ilana.quotes.tg, non.ilana.tg)

all.groups.tg<-c(rep("Ilana", length(ilana.quotes.tg)), rep("NonIlana", length(non.ilana.tg)))

length(all.groups.tg)

[1]

460

“And now, let’s write out the code for creating trigrams.”

%%R

#Function for creating trigrams

#Subs spaces with an underscore, finds start and end points, and applies it to text

makeCharacterTrigrams<-function(dialogue, str.length=3){

dialogue<-gsub(" ", "_", dialogue)

dialogue.sep<-unlist(strsplit(dialogue, ""))

starting.points<-seq(1,(length(dialogue.sep)-(str.length-1)), by=1)

ending.points<-starting.points+(str.length-1)

all.str<-mapply(function(x,y) dialogue.sep[x:y], starting.points, ending.points, SIMPLIFY = F)

all.str<-unlist(lapply(all.str, function(x) paste(x, collapse="")))

return(all.str)

}

“Next, let’s create the trigrams.”

%%R

#Lower-cases all text

all.text.tg<-tolower(all.text.tg)

all.text.length.tg<-unlist(lapply(all.text.tg, function(x) length(unlist(strsplit(x, "")))))

#Identifies quotes with fewer than 3 characters & removes it

badtext.tg<-which(all.text.length.tg < 3)

if (length(badtext.tg) > 0) {

all.text.tg<-all.text.tg[-badtext.tg]

all.groups.tg<-all.groups.tg[-badtext.tg]

}

#Applies trigram-making code to the text

all.trigrams.tg<-lapply(all.text.tg, function(x) makeCharacterTrigrams(x))

all.trigrams.tg<-unlist(lapply(all.trigrams.tg, function(x) paste(x, collapse=" ")))

#Print quote 60 in its trigram form

all.trigrams.tg[60]

[1]

"let et’ t’s ’s_ s_s _se see"