DSC #23: Dawn of the Coasting AI#

by Anastasia Salter, John Murray, and Lee Skallerup Bessette

August 25, 2025

Danger

A note from Quinn

“Dawn on the Coast” is a weird BSC book, and I specifically remember hating it as a kid. Instead of our familiar club members in their usual setting, it brings Dawn to California, where kids are named things like Daffodil and Clover, and she’s got a friend named Sunny. As a west coast person who spent time in California visiting relatives, I didn’t appreciate how the whole thing was portrayed, and I wanted to get back to Stonybrook already.

You might feel that way about this DSC book, too.

Rest assured, the DSC hasn’t sold out to the algorithmic edgelords of Silicon Valley. Each of us has our own take on AI – and we’ve got another book in the works about all that. (We want your input on AI to help us write it!) But Lee went to DHSI and got super excited about Anastasia and John’s vibe coding class and one thing led to another and here we are. “Dawn of the Coasting AI” isn’t the book for you if you’re fundamentally opposed to generative AI on principle. But what we do here at the DSC is walk through, step by step, in a friendly way, how people are actually using computational methods for digital humanities. So if you’re curious what that looks like with AI, read on.

Prelude: The Clankers are Coming#

Anastasia#

You probably feel like you already hear too much about generative AI. I know I groan whenever I get a university-wide email with AI in the headlines, and it doesn’t help that generative AI is coming soon to a learning management system near you. I read the press release of the Instructure and OpenAI partnership that will add all sorts of questionable features to Canvas a few weeks ago, and that’s what finally got us to sit down and write this book.

The first tool they are promising in that press release is an “LLM-enabled” assignment:

…designed to let educators create a custom GPT-like experience within Canvas. Teachers can define how AI interacts with students, set specific learning goals and objectives and determine what evidence of learning it should track. They can do this using natural language prompts or by leveraging an assistant within the assignment creation flow to guide them through the process.

Here’s the thing: I teach lots of assignments that do involve working with LLMs. None of them would ever look like that. It’s the sort of use case that makes me sympathize with the folks rolling out the Star Wars lingo and calling bots (and the folks who over-rely on them for life choices and companionship) “clankers.” And that’s even though there are plenty of folks who would say I’m doing too much with AI myself.

Bringing chatbots into the classroom, particularly at this stage of their evolution and without any real input from educators, makes me recall a very old BSC book from my own childhood: “The Truth about Stacey”. The b-plot of that book is a competition with a rival agency of older babysitters who build a centralized hub for finding a babysitter. They turn out to be a mess - one of the kids, Jamie, tells the BSC about a sitter who brought over her boyfriend and smoked cigarettes - and the depersonalization of the whole experience eventually drives most of the clients back to our regular BSC.

The BSC “wins” against the rival club by offering human connection instead of a factory-ized service, in spite of their earlier bed times (the rivals are college students). The BSC members double down on bringing toys, doing crafts, and caring about the kids they sit - all things I think about looking at the news out of Texas of an “AI-powered” private school. The thought of handing over any critical aspect of education to a bot is enough to make me, a fairly tech-dependent DH’er type and former ProfHacker, reach for pen and paper. Speaking of ProfHacker - thirteen years ago (!!) I wrote a post for the old group digital humanities column entitled “Robot Writers, Robot Readers,” at a moment when a now adorably quaint “essay writer” site was circulating. The future I was worried about, robot graders evaluating robot essays, has arrived. For more on this moment in higher education, I recommend listening to the “Et Tu, American Federation of Teachers?” episode of Mystery AI Hype Theater 3000.

(Lee: I also wrote ages ago about how adjuncts were basically forced to be grading machines, and thus why actual machine grading would always be more efficient [but not better], and I can’t for the life of me find it online. There is something to be said about the adjunctification of higher education and ed-tech “efficiency” - but I digress…)

But here’s the thing - in the Datasitter’s Club, and for that matter digital humanities, we have lots of potential use cases for generative AI tools that don’t involve letting them teach our classes, write our papers, or grade anything. generative AI tools raise lots of other questions and possibilities, some of which the club has talked about before when LLMs were still a novelty. So, in this book (inspired by “Dawn on the Coast”, in which Dawn visits California and is almost lured in by its cool factor) we acknowledge that Silicon Valley is pushing a lot of edtech solutionism with dangerous implications for the already precarious future of higher education. However, we want to think about generative AI through a digital humanities lens: can these tools be a part of our DSC kit?

Certainly, they are already a part of mine, but almost exclusively in the context of code. John Murray and I taught a workshop for Digital Humanities Summer Institute, “DH Programming Pedagogy in the Age of AI,” focused on those questions and possibilities: what does it mean to bring generative AI coding into our work and classrooms, and how can we approach it thoughtfully? To begin to answer those questions, John and I sat down to discuss the problem.

Lee says…

I took their course at DHSI, and I’ll be interjecting throughout in my positionality as a student learning these things for the first time.

Of Code and Pedagogy#

Anastasia and John#

Anastasia: So I’ve been thinking a lot about the rip-off BSCs that pop up throughout the series, including in one of the earliest books, “The Truth About Stacey” - a book I actually owned in paperback from a book signing with Ann M. Martin when I was a kid. Of course, I lost that copy. But it reminds me of the nonsense OpenAI is selling right now about on-demand course assistance and an on-call PhD - the rip-off club hired a bunch of college students.

John: Right, they don’t have bedtimes.

Anastasia: Yes. They don’t have bedtimes and also you can call a line and you get somebody right away as opposed to just this group of a few kids where one of them may not be available for your Friday night date.

John: The centralization and factory-ization.

Anastasia: The club’s response is to emphasize their human connection and their Kid-Kits that they take with toys and crafts and those sorts of personal things.

John: And that they know the kids.

Anastasia: Yup. And so it’s all this like, the human connection versus the depersonalized service - which is exactly what we’re seeing with higher education right now. I’ve read lots of people talking about going back to oral exams, making zines in classes, blue books - all things that require a lot of hands-on time. It doesn’t scale. AI, on the other hand, is all about scale - and I think that speaks to why educators especially are going to have a lot of trouble wanting to work with any of these things right now. What OpenAI just announced is truly the worst.

John: What is OpenAI really promising with all their current hype?

Anastasia: Right now, they’re saying that they’re going to integrate in a bunch of grading and instructional tools that are supposed to reduce the amount of time people have to spend grading and writing feedback; those are supposed to be able to use your rubrics that are built into Canvas. So one of the cases they described was a personalization case: if a student has an emergency and you need to change the due dates for just them for the next three assignments, you should be able to use a prompt-based interface to do that.

John: As opposed to the graphical interface, which is actually awful.

Anastasia: It is so bad.

John: They have a point there.

Anastasia: I mean, it is the worst. It’s okay to acknowledge that it is in fact absolutely terrible to work in the LMS now.

John: Changing all the due dates and adapting them for a new semester shouldn’t be as hard as it was - is.

Anastasia: No, there’s lots of things about the Canvas interface that suck, and there are several times when I’ve been working with the agent-based tools which we’re gonna be talking about in this book that I would like to actually be able to let my agent do: “update every reference in here,” “fix the assignment deadlines based on what you just did with the schedule”, “remove all mentions of the hurricane”

John: These edits are doable through more complex tools, like the API - Application Programming Interface - which provides a means to talk directly to the software system, skilling the interface. Tapping into that with agents would basically let you make those sorts of changes - but there is a lot of technical set-up involved.

Anastasia: Sure, you can do it with the API, but most of us won’t.

John: But building it directly in the Canvas is obviously better, but then you can only use OpenAI’s tools - we’ll be locked in to their agents and ecosystem.

Anastasia: That is going to be the problem, and not only that, but there’s very real questions about FERPA and data surveillance that are coming up already, and there are only going to be more such questions as we go through this. There should be because I have really strong concerns about what these contracts are going to look like and what it’s going to mean for the institution to do this.

And it also goes right back to the part where some of our colleagues, if they in fact follow the institution’s advice and only use the tools that we’re provided for things related to campus activity, are getting a really narrow view of what these things are because they’re locked in to not-great chatbots - and our students are going to have their views shaped by interactions with those systems as well.

John: The Open AI partnership with Canvas actually is motivating me to think about building open source tools for educators and releasing them for free as soon as possible because it’s just going to be the alternative and maybe, maybe even it might not even be allowed.

Anastasia: That question of what is going to be allowed is a big one, and there’s already folks (including me) thinking about going old school if you don’t want your content to become part of Canvas’s OpenAI partnership data. Agent-based AI tools are great for building web classes with interfaces and experiences that are separate from that ecosystem, but not every university is going to even let us do that. But it seems to me that rolling your own site again, going back to some of our old school DH practices is a really good way to escape the AI layer and still give your students all the online content they expect.

John: Because you know what this partnership will likely involve: just what you’ve said, contributing Canvas course content and getting it back to OpenAI for their training. Not to mention student content, and interaction data.

Anastasia: Yeah, we just watched Johns Hopkins University press send notice to their authors that everything’s going to be used to train models unless they sign an opt-out agreement. I already build as much as I can outside Canvas to be shareable. And I know that when I do that, it is available not just to one model, it’s available to lots of models. And that’s actually what I’d prefer. I’d rather contribute to the whole ecosystem and put things out for open knowledge than have my stuff locked up in Sam Altman’s world. I’ve been reading Empire of AI, which really speaks to why Sam Altman’s world and vision is particularly concerning. And that’s, I think, important here as well. It’s not just that they made a deal. Canvas made a deal with, of the players, if not the worst, certainly a competitor for worst.

Lee says…

Academic Bluesky had an absolute field day with the announcement from Altman that the new version of ChatGPT would be like having five PhDs in your pocket. I already have five+ PhDs in my pocket - it’s called the DSC group chat, and I highly doubt whatever ChatGPT has come out with even remotely would give me what this group chat gives me, but again, I digress…

John: I mean, my approach has always been that you’ve got to have multiple models to leverage, to shore up each other’s deficiencies. Yeah. I’d rather have three different models work on a problem and then allow me to review all of their differences as kind of a meta-reviewer than to be stuck in one AI’s models world view and perceptions. These tools actually are better if you can play them off of each other and have them critique each other. But if you have just one model involved in anything it won’t be nearly as good.

Anastasia: Well, and you’re also, right, so contextually, we’re talking about large classes and all of the realities of working at an institution like UCF, which is not in fact the ideal (laugh). And that’s exactly who the OpenAI solutions are going to be most appealing to–my grad students who are being assigned to teach 140-person classes. Like, I’m not going to tell them not to use it, honestly. But I will tell them that I don’t think the tools that they’re going to get through OpenAI are going to be the best tools for the problem.

John: No, because the people designing those tools don’t understand the pedagogy or the concepts of how to use it effectively in every case. And that’s where they’re constraining the innovation, really, that the instructors could bring to bear it by the more guardrails they put on it.

Anastasia: Yeah. But my other concern with all that is that I mean, in the case of my students, if they’ve taken my AI classes and really thought through some of these things, they know how to go and do something that would not compromise student data. But a lot of people do not, in fact, understand what’s happening when they use a free web model. So there are almost certainly lots of FERPA violations related to AI happening right now. And also a bunch in the peer reviewing process because people are absolutely feeding most papers to all sorts of things. So we have a fundamental problem of literacy.

Anastasia: So, I guess the question is, how do we build that literacy through the digital humanities? That’s really why we’re here, guest-sitting in the DSC as fall semester is crashing down - to talk about why we find agentic AI tools useful in digital humanities, and where we teach with them, and how that differs from what edtech is selling everyone.

John: Agreed - and to go back to the BSC, one agent is useful, but you can have your own coder’s club, your own six always on-call agents, and maybe that’s the most terrifying stuff there is.

Anastasia: Perhaps. But it is where it’s going, because each individual agent is limited.

John: Yeah. These limitations start to become more and more apparent.

Anastasia: Yeah, we saw that teaching programming at DHSI - it’s powerful, but there’s also a need to build new literacies, and the frustration points can be just as bad as any type of coding.

John: It’s also worth noting that all the best tools for working with this stuff do in fact involve the terminal at this point. So there’s another interface literacy involved, and doing things like controlling your own content, and yes, even with GitHub, you’re still throwing it into somebody else’s ecosystem of shitty tech. Regardless of which of these things you’re working with, there’s all those other literacies. For this DSC book, we should spend a little time talking about Visual Studio Code. A lot of the DSC work has involved Python, which is also changing dramatically right now - whether you use Colab, with Gemini built in, or manage your own environments, agents are changing how we do and our students will do this work.

John: Using these tools intentionally gets to the heart of why we frame this work as “distant coding.” You might have seen articles go by where folks have talked about doing vibe physics and vibe science, how they think they’re pushing the frontiers of scientific research when they are just talking to a chatbot. And I think that stuff is a really good explanation for why the language of “vibe” coding is so troubling. The idea of it - build complex systems without ever looking at the code - allows people to think that because they’re talking to this chatbot that they have the expertise. And that’s really dangerous, especially from a security standpoint.

Anastasia: So distant coding offers us a place to intervene through a digital humanities lens, with parallels to how distant reading doesn’t replace reading, it augments the practice and allows us to do different things. We do need to preserve the significance of human expertise and the importance of going back and forth between looking at and interacting with the code and working with the code at a distance through these interfaces and tools. Otherwise, you have no responsibility for or integration of human expertise into the outcome.

John: There’s also the problem of AI agents designed to please and to be overly positive and basically wanting to give the user whatever they want, which leads to these “you’re creating this breakthrough” and “great job” and all that, which can lead to overconfidence in vibe coding.

Anastasia: This is also a challenge for the students that are going to be using these tools, because potentially even the people teaching them don’t know that these are problems. And as agentic AI is going to be normalized, a lot of these concerns about lack of expertise are also going to be dismissed and swept under the rug.

John: Yeah, well, and we’re going to get the curriculum as brought to you by edtech and a lot of companies. It’s going to make that even worse. And everything that you ask it to do, it might inject or inflect positive perspectives on AI. And that might affect a lot of assignments in the future just by that kind of optimism that AI has built in its own future that maybe could skip some of the criticism that is valid, just because it’s being used to generate assignments by instructors now using the OpenAI tools.

Anastasia: We’re also going to have to reckon with the consequences of the AI executive orders and policy rollbacks. If in fact this administration is successful in their crusade against so-called woke AI, then we’re going to have to deal with the fact that a lot of these tools are going to have things embedded in them in ways that might not immediately be obvious in terms of their consequences for code. For instance, let’s say you ask an agentic AI to build a survey with a gender field. What it gives as a response - I mean, right now, it’s probably already not great. Because it’s already drawing from what’s most common practice in things like code base, like all the open source software on GitHub. It’s already going to get a bunch of male-female stuff from that. But it’s only going to get worse. And we might even get to the point where, if they are successful with some of this, where it actually just refuses to do anything different. And that’ll be fascinating, dystopian hellscape stuff.

John: Same sort of thing we were accusing the Chinese AI sponsors of embedding in their models.

Anastasia: Yes. Oh, the hypocrisy of it all. Yes, at our institution we received a “you cannot use DeepSeek” warning. I believe in that announcement, they did not differentiate between the model and the web service as well, but it is the web service that is banned on Florida state networks. Meanwhile, Grok appears on people’s tool lists and might well make its way into campus partnerships - and DeepSeek is the problem? Okay. Let’s talk about your sexualized anime AI chatbots over there, folks.

John: Probably not the best examples of the future of AI.

Anastasia: But inescapably part of it.

John: And on that note…maybe we should build some things.

Lee says…

While I was taking their course, I was able to (using their tutorial) a) scrape Project Gutenberg’s collection of Canadian literature, b) change all the files names, c) scrape the metadata and turn it into a CSV, and (most problematically) d) run a topic model on the corpus - all using AI. I didn’t have to worry about the command line, or R code or anything. I just…worked with AI to do the things. And it only took me about 30 minutes. Now, I was doing really simple DH tasks, but often those same tasks can be roadblocks. I also have a basic understanding of metadata, corpuses, file structure, etc, because of my work in and with DH, so I could understand if what the AI was giving me was actually what I wanted. Now, when it came to the question of topic modeling, well, it was asked more as a joke because topic modeling is kinda my DH blind spot, so I could present the results (jokingly) and being like, see TOPIC MODELING, even though I know I have almost zero understanding of it, let along what the AI did to get to whatever topic models it presented me with. So AI can definitely lower the barrier to entry to DH by doing some of the grunt work, but you still have to understand what it is you want the AI to do to know if it was successful in doing it. For instance, just asking the AI to “clean your data” won’t be all that useful, because, well, what does that even mean?

I had a similar conversation with a history professor who studies a small, long-lost culture and language. AI can help digitize, transcribe, and translate documents, work that would be too much for one (or even a handful) of researchers’ lifetimes. But, you still need the experience and expertise to ensure that the work the AI is doing is accurate AND to know what questions to ask of the data/materials after the fact. HOWEVER, as a teacher, many students are using AI to shortcut the actual learning of the skills and knowledge necessary to eventually ask the right questions and make sense of answers. It’s the same thing in DH - AI can speed up processes, but unless we understand what the processes do and why we would want to do them, then we’re just going through the motions and not actually engaging in scholarship.

Building a Website with GitHub Copilot Agents#

Anastasia#

In “Dawn on the Coast”, Dawn visits an “inspired by” BSC club with lots of California touches, like healthier snacks and cookbooks for kids. The group has even copied the kid-kits - “boxes that we fill with all kinds of things for kids to play with — books, games, crayons, puzzles. We bring them to the houses we baby-sit at and, of course, the kids just love them. They’re also good for business. They show we really are concerned and involved sitters.” I’m not saying I approach my teaching and scholarly work quite like a kid-kit, but there’s certainly some elements of style and interactivity that I approach in that same way.

Agentic distant coding, where the model uses tools, builds files, and makes edits directly, can be used for just about any type of programming - but I mostly use it for web development because so much of my work falls into that category, both in preparing my classes and building scholarly, weird things for other people to interact with. So as an example of how generative AI can expand our “Kid-Kits,” as it were—our educational materials, visualizations, public scholarship projects, etc.—I decided to build a BSC educational “tech” visualization site.

I didn’t want to spend much time on the Python part of that effort (for more on Python, see John’s section below), so I used the new Claude Opus 4.1 to make a quick Jupyter notebook for building a JSON concordance of some of the most-mentioned examples of old tech in the BSC series. The prompt I used was fairly basic, and the notebook worked on the first go:

Build a Jupyter notebook for deploying on Google Colab that takes a large number of pre-processed novels as an upload, searches them for any mention of 1990s and 2000s appropriate educational technology (broadly defined), and builds a JSON concordance of the results with the top twenty edtech items mentioned and the eight word context of their mentions.

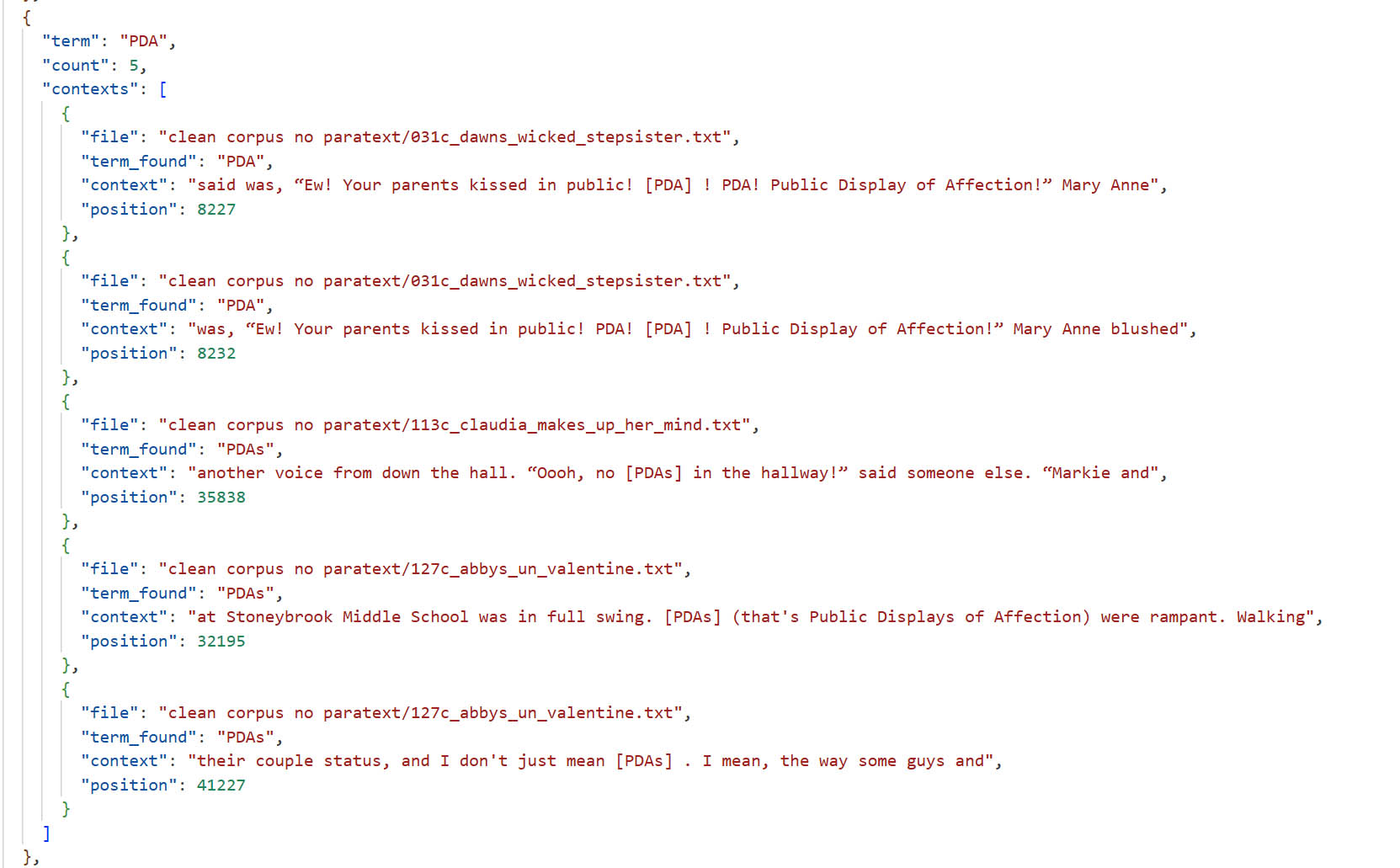

I did have to do some hilarious refinement on the terms it suggested - for instance, PDA (Claude was thinking of Palm Pilots) only came up in the dataset in a slightly different context:

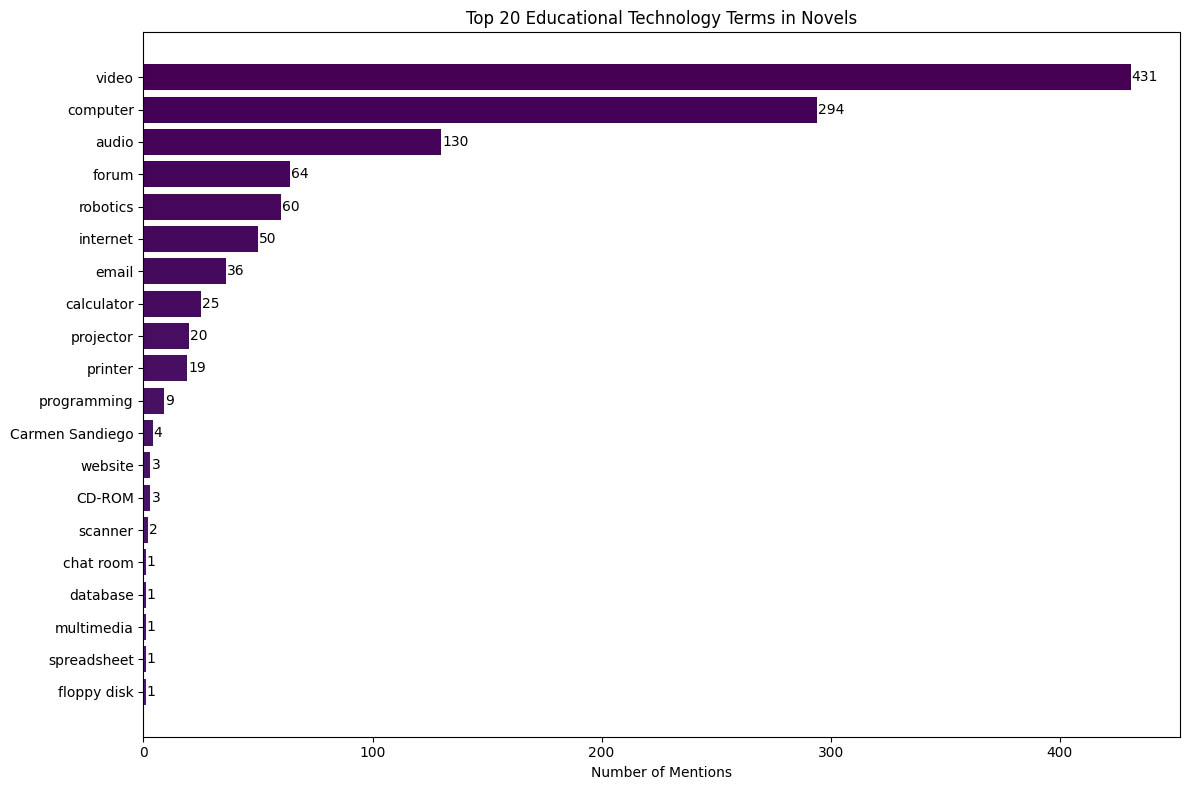

Once those terms were sorted out, I left a few that were entertainingly ambiguous (“Web” showed up both for the World Wide Web and Charlotte’s Web, for instance) and ran the visualization and final concordance. Unsurprisingly, some retro tech rose to the forefront:

I didn’t differentiate between mentions of tech that were contextualized in education versus daily life for this, so it isn’t surprising video (subset: 'video', 'videos', 'educational video', 'VHS', 'videotape', 'video cassette') won by a landslide. This fairly boring visualization of occurrences was part of the original notebook generated by Claude.

This isn’t amazing data, but it is fun (especially for geriatric millennials like myself) and it gives us a web-ready file to play with. You’ve probably heard plenty of the risk of AI “hallucinations” - I’m not particularly a fan of that term, as it contributes to treating models through a human lens, but it is true that in the absence of data, AI will fill in the gaps with nonsense. So, to play with visualizing data using agentic AI, I brought it over into Visual Studio Code.

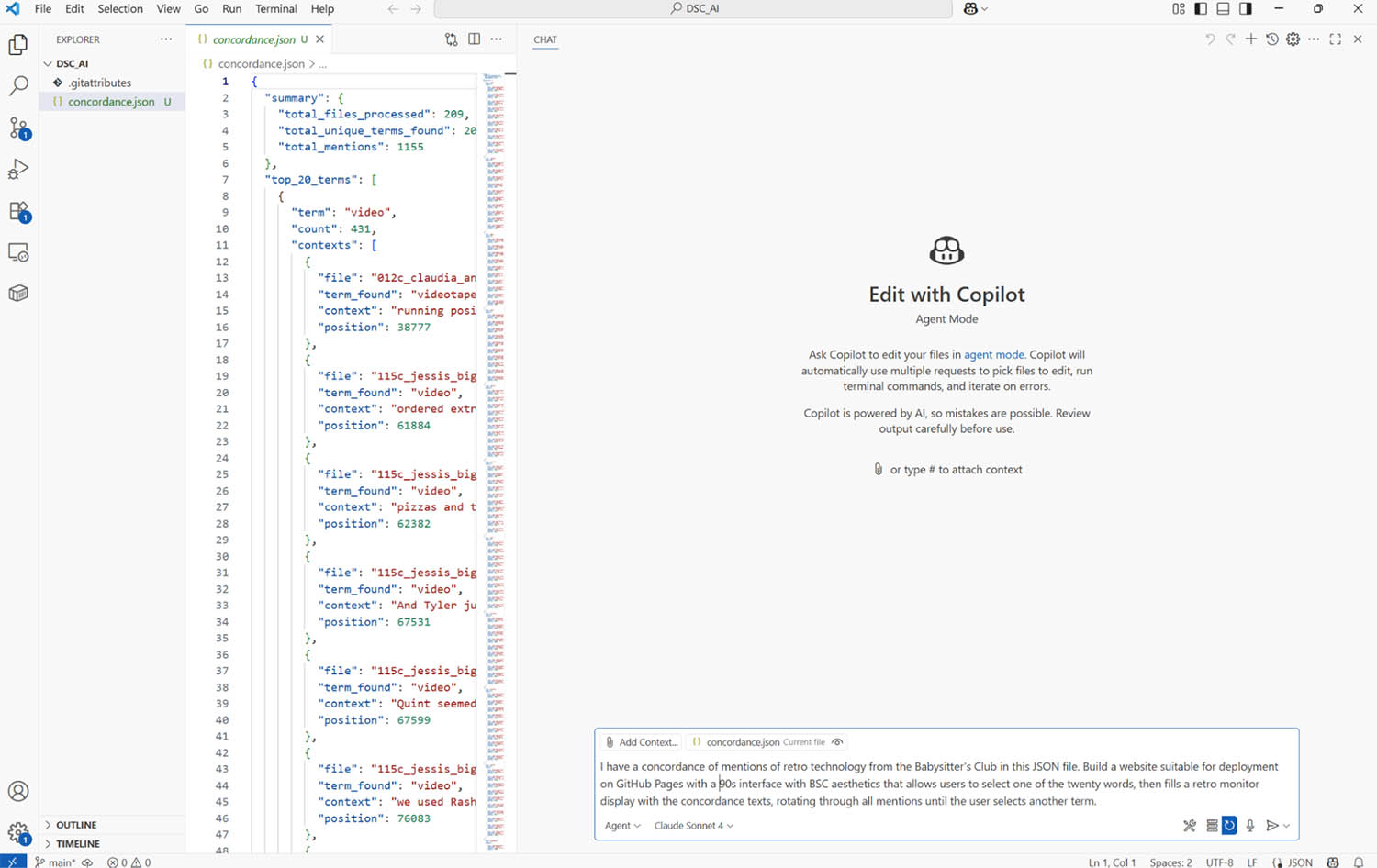

My current favorite way to work with agentic AI and generative AI tools for pretty much everything I do with distant coding is through the GitHub Copilot tools. For fellow educators and students, one advantage to this approach is you can currently get free access to this by enrolling in the GitHub Education program: it requires a tedious verification process - it uses geolocation-driven barriers as part of creating an account. If you’re not currently near your campus, it will give you a bit of a hassle on verifying your identity.

If you’re at a Microsoft campus (as I, sadly, am) you might have access to a “Copilot” already. That is not the one I’m talking about, as it’s just a watered down chatbot. GitHub Copilot is an integrated development tool that’s model-agnostic (it offers several choices right now, and can also work with models run locally) and hyperfocused on programming.Basically, you get access to current models integrated right into your IDE development environment where the coding happens. If you’ve generated any code with a generative AI tool—maybe Python code or HTML or structured data or whatever—through a chatbot in a browser, there are a lot of other fussy steps involved. You have to track where things go, and the longer and more complicated it gets, the less context it has for the whole project. There are lots of things that make that approach to distant coding frustrating.

By contrast, Visual Studio Code is very much a programmer’s environment, so it’s ideal for complex projects - and it is also overwhelming and filled with features, particularly if like me you grew up thinking Notepad++ was as good as a code editor can get. If you haven’t used Visual Studio Code before and want to try it, I recommend downloading it, then making sure you’ve connected it to your GitHub account (installing GitHub Desktop is a shortcut to this process). The extensions I rely on for distant coding are primarily Live Preview, for testing the website as it progresses, and GitHub Copilot itself with agent mode.

Once you’re in Visual Studio Code and you’ve logged into GitHub Copilot with an education account, load Copilot by clicking on the little goggled avatar in the side top. The interface is pretty straightforward compared to the rest of VSC: it’s basically just like your text prompt but with a few fancier features.

Here, I’ve loaded the concordance into an empty repository, and selected “Agent” and “Claude Sonnet 4” from the options. Notice the “Add Context” feature - while the agent will work across all the files in the folder, this is a way to direct the gaze to specific things for queries. Agent mode is the only setting where we let the tool change our files—a little frightening, “ghost in the machine” style—but it also spares us a lot of management work. The option to “keep” and “undo” changes helps, which is where live preview comes in: if something goes totally off-kilter, that’s a way to quickly reset. It’s also possible to use the other modes for getting suggestions and evaluating them before implementing, which is more important when the project is complicated.

So, once the agent is directed to the structured data file, the development cycle begins through prompting just like any bot. Since agent mode takes me back to the golden age of GeoCities and LiveJournal, and there’s a similar sense that you’re playing within a community of shared code, I started with a prompt pulling in those retro aesthetics while describing the goals of the selection interface:

I have a concordance of mentions of retro technology from the Babysitter’s Club in this JSON file. Build a website suitable for deployment on GitHub Pages with a 90s interface with BSC aesthetics that allows users to select one of the twenty words, then fills a retro monitor display with the concordance texts, rotating through all mentions until the user selects another term.

The workflow becomes really straightforward. The more specific you are in your language—as far as the type of website you want, how you’re going to deploy it, aesthetics, interface, even libraries (like mentioning a library like D3 for data visualization)—and the better structured your data or content is beforehand, the better results you’ll get. It helps that when we’re talking about this interface for a course website or public humanities projects, we don’t typically have the baggage of “what happens if you’re building something where there are actually security risks around the software” or those critical concerns. Here’s the first iteration after a single prompt:

It’s quite serviceable - pick a term, go through the concordance and see the mentions - but there’s lots of things worth fixing, including getting rid of that slightly over the top menu of buttons. I went through a number of iterations with prompts asking for stylistic changes as well as practical changes around the display of the filename versus the book title - you’ll notice there are still a few problems with that in the final, as I didn’t go through the full hassle of dealing with punctuation that isn’t in place in the filenames parsed.

Here’s an in-progress iteration that shows some of the challenges of asking for particular aesthetics - the organization doesn’t make much sense, and the animation (thankfully not captured in this screenshot) is overwhelming.

However, I could quickly correct that with specific prompts, as captured in the “Visualizing with Agents” sub-page - also generated, with the chat transcript from this project as the source. I’ve left some of the hilarity, like the Claude Sonnet 4 generated description: “This retro concordance interface was entirely built through a conversation with AI agents. The process demonstrates how modern AI tools can translate creative ideas into functional web applications, complete with 90s aesthetics, responsive design, and interactive features—all through natural language instructions.”

The final version of this visualization is deployed on GitHub Pages, which fits well with the workflow of using GitHub’s repositories to track changes and versions over time, and makes it easier to have students host work. I have assignments that take students through this process, including deployment, in my Humanities in the Age of AI course on an open-access Pages site - with layouts and styling also generated using this workflow.

Part of the promise of this workflow from my perspective is the ability to eliminate unwieldy frameworks like WordPress. Building client-site only sites to a particular purpose has already freed me from a lot of overly complicated code. I now find for most projects I either use generative AI to assist in refining layouts for a static site or I go straight to fairly basic HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, keeping that content free of some of those more annoying dependencies and structures. My legacy WordPress sites have together brought me the headaches of a million messages involving attacks and PHP exploits - most of them are now offline to avoid the constant maintenance. When we work with native web technology, we avoid all that.

Returning to the idea of “coasting AI” that we opened with: I acknowledge that these tools are making me lazy in lots of ways - see also the fact that this was written from an AudioPen transcription, which is another tool I use constantly because of carpal tunnel from playing all those video games in the ’90s. However, this is also giving me the bandwidth to do things I would never have gotten to, like actually update my website for the first time in years. The original site was locked into a dated theme, and bringing in new structured content was as simple as dropping in the JSON file in this project. (It’s also built in a ’90s aesthetic that I described as “Trapper Keeper style,” which apparently has plenty of reference material in Sonnet 4’s dataset.)

At the same time, literacy of libraries and tools is still critical for doing anything more complicated. The back and forth process benefits from our ability to specifically reference a library like p5.js and to define things in concrete terms. This is why when I teach distant coding, I assign readings from Code to Joy by Michael Littman, which I highly recommend to folks diving into this way of working or just playing around with programming in digital humanities. His approach is focused on the language of coding and understanding the operations and principles more so than the syntax of code.

Agents on Call#

Lee#

I did nothing like this, but I did distant code this cool e-lit piece and re-did my personal website. Blew my mind.

For the piece of e-lit, I set up my distant coding environment using Claude agent from GitHib in VS Code and then Creative Code with ML5/Face Mesh. I used the raw text from my eLit project Moving In and Out of Time and had Claude turn it into a CSV file with each value being one sentence. I then took the Face Mesh program and worked with the Claude agent to make it so that every time the mouth was opened, random sentences from the CSV file would fall out, creating - as I was finally able to accurately describe to Claude to get what I wanted - a wall of text that would eventually cover or “drown” the speaker. I also had it randomly make sentences in black so they would stand out and be easier to read. Finally, I made it so that the words never stopped falling, but instead would speed up the more the person opened their mouth. I have no idea what Ana and John were trying to teach the rest of the class at the time, but I spent an afternoon going back and forth with the Claude agent to get the effect I wanted.

Now, as for my new personal website, I had the Claude agent create a clean, modern format for the site, and then fed it my CV, my list of publications from Google Scholar, and some writing samples, asking it to create a personal, professional website. We went back and forth for probably a total of 8 hours, again with me not paying attention to what I was actually supposed to be doing in the course, but also at night when I couldn’t sleep in my dorm room. It was a conversation - I would tell Claude I wanted to change the order of the materials presented, or fix the spacing, or to stop making up publications for me because I had already given it my actual list of publications. When I was satisfied with one part, I’d move on to the next, and then added other sections and pages. I didn’t write most of the text on the site - Claude generated it based on my prompts and my writing samples. Honestly, I’ve always struggled with making myself sound professional, and this is the most professional I’ve ever appeared on the web. I had a lot of fun making it; honestly, the hardest part is getting the GitHub Education account, and then installing everything in the right order so that everything syncs. And I’ve used GitHub before as well as different coding environments, so there was less of a learning curve for me.

I’ve been an AI skeptic, and hadn’t really used it in my day-to-day because, well, I couldn’t find anywhere where using some form of AI would actually help me. As someone with ADHD, redistributing the cognitive load is an attractive proposition, but getting the AI to work the way I want/need it to is an ADHD nightmare, so I’ve just stuck with what I’ve been doing which works pretty well for me. This revelation of possible uses of AI was jarring, because I could see myself using it for doing creative eLit work or rebuilding my website that I have been putting off but also wouldn’t ever pay someone else to do. I keep going back to what Martha Burtis said about friction being a feature not a bug when it comes to learning - in this case talking about Domain of One’s Own - and I can’t help but pause on how relatively frictionless all of this was. I didn’t really learn anything, other than I can use Claude agent to avoid learning, although if I used it the way Ana and John wanted me to use it, I would have learned some (more) rudimentary coding skills. I could have asked Claude to explain to me what parts of the code were responsible for what parts of the site or the Word Vomit experiment, but I didn’t, because I was now focused on product rather than process. Which, again, appeals to my ADHD brain because I don’t want to do all the detail-oriented grunt-work of coding and looking for my mistakes in the code and installing everything in the right order and doing the commands just-so, etc. I get to jump to the fun part, which is making something. I get the appeal! I do!

One of my responsibilities as a faculty member in the Learning, Design, and Technology MA program at Georgetown is to guide students through the process of creating their capstone ePortfolios/personal websites, which are required for graduation. I try to spend more time on the content than on the actual technological side of building their sites, because it doesn’t matter how “pretty” their sites look, if they don’t have any meaningful content. We provide hosting and WordPress, but many of them are - rightfully - frustrated by the platform now, and choose to pay for a different proprietary content management system/website builder. Which…Is teaching them how to use Claude agent and Github Pages better or worse than Wix or Squarespace? This would really get the technology out of the way and allow them to focus on content, narrative aesthetic, etc. And part of me REALLY wants to never have to deal with WordPress again anymore, although I supposed at the end of the day I could distant code WordPress to do my bidding and I’m back where I started.

All of this to say, I’m happy with what I learned and accomplished. I’m glad we’re lowering some barriers to entry to DH and other kinds of digital experiments, but I don’t want to lose what makes this fun and worthwhile - struggling alongside other people to figure stuff out. One more step towards I don’t need other people anymore, only AI. I don’t want to replace the five PhDs I already have in my pocket with the ones Altman wants to give us.

Data analysis with Colab and Gemini Agents#

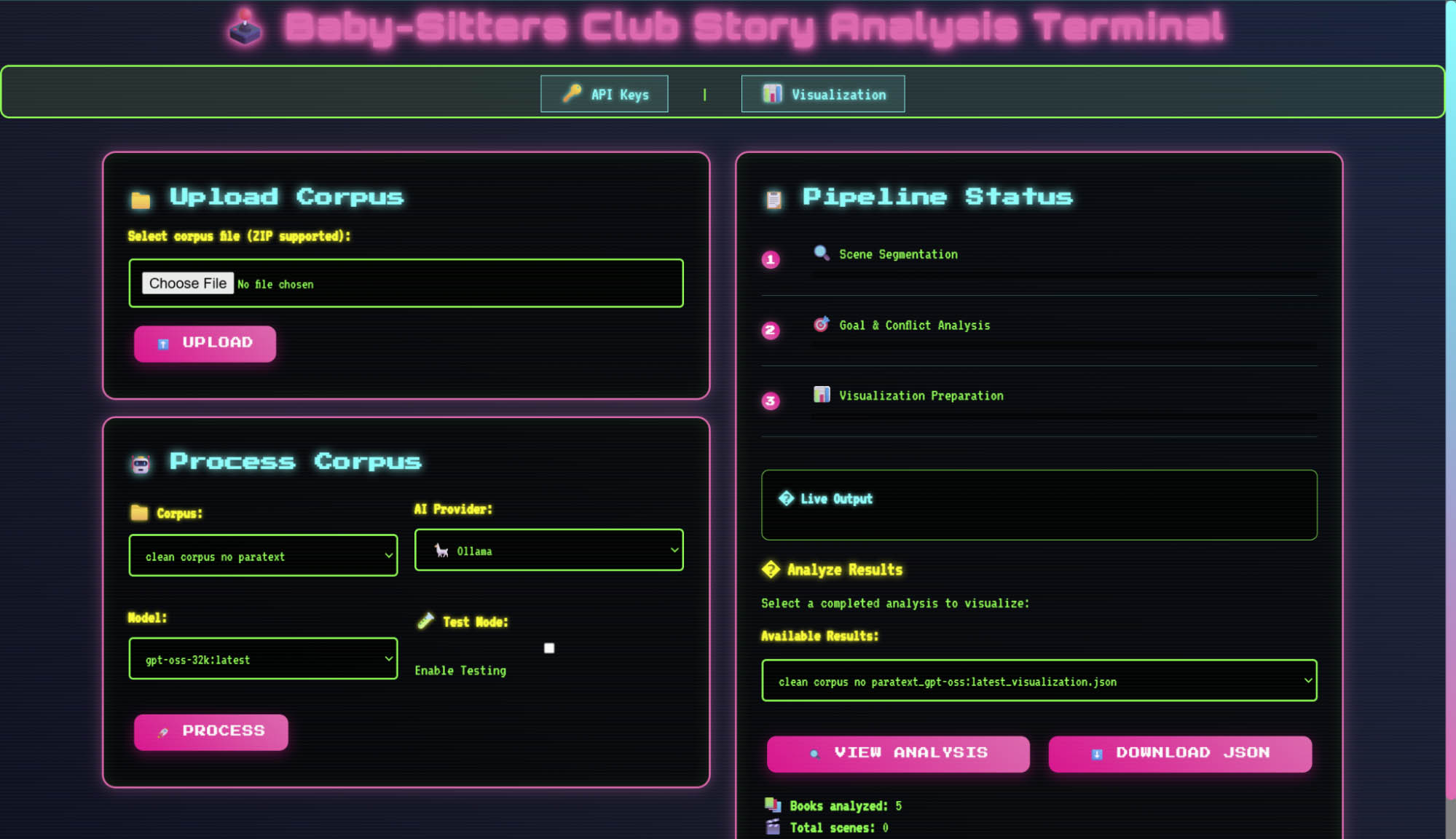

John#

I learn best by working through a project. While we had recorded our conversation using AudioPen, I wasn’t very happy with the transcript, so I started looking into ways to improve the transcript, and thought that it’d be a good chance to use local models. I was similarly excited to dig into narrative processing after looking over the Babysitters Club corpus.

What types of analysis can we do across a large number of related stories using large language models? And can local open-weight models (such as the recently released OpenAI OSS model) identify complex concepts such as a character’s “goals” and “conflicts”?

This pulled me back in time to my own dissertation work where I studied a narrative game (“The Wolf Among Us” by Telltale Games) and ended up extending an annotation format for narratives developed by David Elson: Story Intention Graphs. In essence, they allow a formal way to talk about the entities, events and relationships in stories and draw from linguistics heavily.

Instead of attempting to encode the Baby Sitters Club books using SIGs directly for this project (maybe later), I thought that goal identification might be a good balance between using LLM-specific capabilities (natural language processing beyond entity-recognition or statistics) and simplicity. This is a great time to experiment with AI to discover what it can be used for, both smaller and larger models, and narrative theory offers some useful frameworks.

I’ll describe my approach through both projects below, with an emphasis on some of the principles I’ve discovered and some of the challenges I faced. Generally, it’s best to work directly with the agents and to scrutinize the outputs prior to running something that takes a long time. Today’s models are prone to declare success or to miss critical insights, especially as projects get bigger. This complexity ceiling is important, as it suggests that anytime some feature is “patched” on, it is best to direct the same agent to simplify and rewrite things. Programmers often fall into the same trap of postponing refactoring and to just make things work by making small modifications.

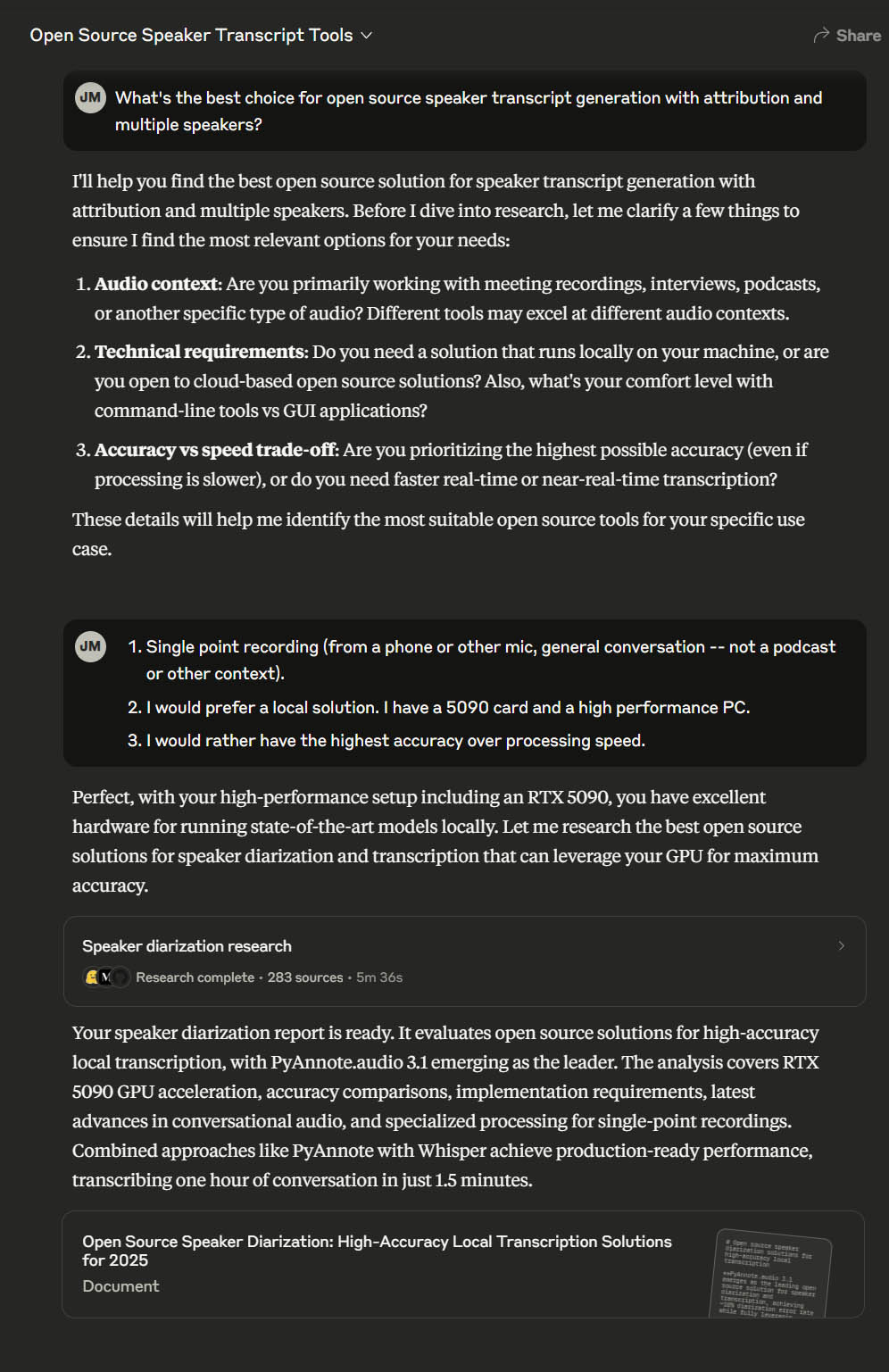

I’ll start with the “speaker diarization” (which is assigning labels to segments of a voice transcript based on speaker identity). I used Claude to do deep research to help me determine which models and techniques were the “best.” I find deep research (either Claude or ChatGPT) can sift through evaluations and openly available tools and offer a good starting point. I’ve even used it to research big purchase decisions such as PCs and laptops, though in the end it can still miss critical factors that are underrepresented in the available sources, just like humans.

Going from research to implementation involved asking it for an implementation-focused description that I could then pass into another tool to do the work of development. While I could easily use ChatGPT, VS Code Copilot, or even another tool to finish implementation, Claude produced a full document including samples of python code and advice on Huggingface models and configuration. You can find my work here on GitHub, though you’ll need to register with Huggingface to access those models.

The hardest part was making sure the system would run on my system, and to agree to the terms through my logged-in account on HuggingFace.

The first output was already better than trying to identify speakers from the raw transcript. It assigned speakers based on the voice itself, so there was a speaker 1 and a speaker 2. I asked Copilot Chat to rename the speakers to Anastasia and John and it created a script to do it.

It was mostly successful – it couldn’t handle when we spoke over one another, and sometimes it missed interjections, but overall it was way more effective using the audio segmentation than just trying to identify individual speakers from the text alone.

Since there are many models that can handle transcripts, they have become a valuable source of data for local and remote LLMs. I would much rather record my own audio and process it than rely on Zoom or other products for meetings, and have already used this method to create draft notes for meetings with graduate students.

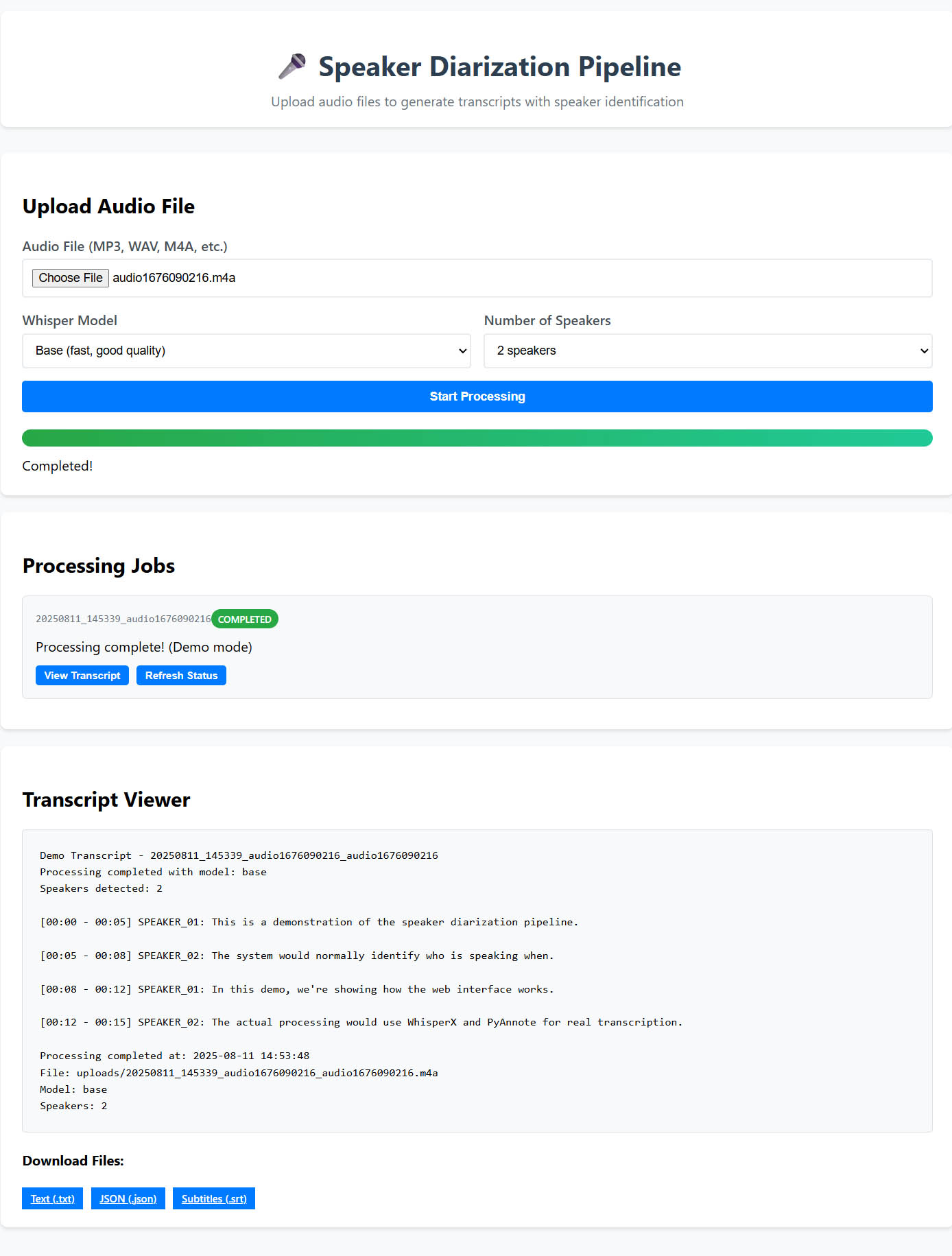

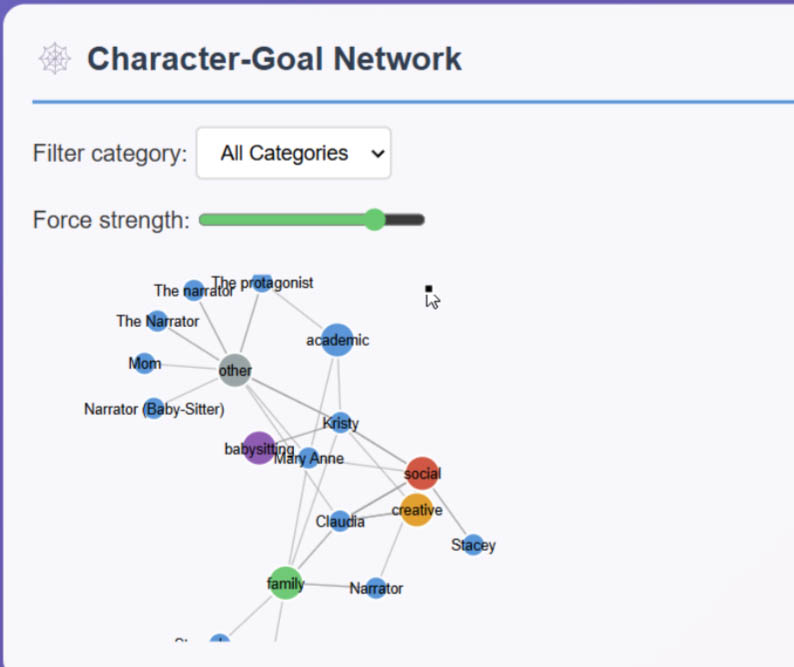

I added a web UI as a final step, asking it to be done in Python. It produced the above UI, which I then requested it to be adapted for the actual python code (rather than a demo version shown). I appreciate the ability for LLMs to produce reasonable UIs even for longer-running local programs. You can find the finished codebase (including the web UI) at the GitHub repository.

Narrative Processing#

For the next part, I returned to one of my research topics: story understanding and visualization. I took a simple approach: consider what would be BOTH tedious and yet not easily analyzed through traditional natural language techniques. This would likely be a good match for LLMs.

I started with ChatGPT and opened up the newly released GPT-5. When I saw the baby sitter’s club corpus, I remembered one of the goals from my dissertation work, shared by many who use annotation: automatic annotation possibly even using the full set of encoding elements from the model I based my work on. This would include named entities, events, values and goals. I quickly fed it a description of the annotation format and an overview of the goals and the corpus. The approach it recommended is one I hope to pursue, but was much too complex for a first project with the corpus.

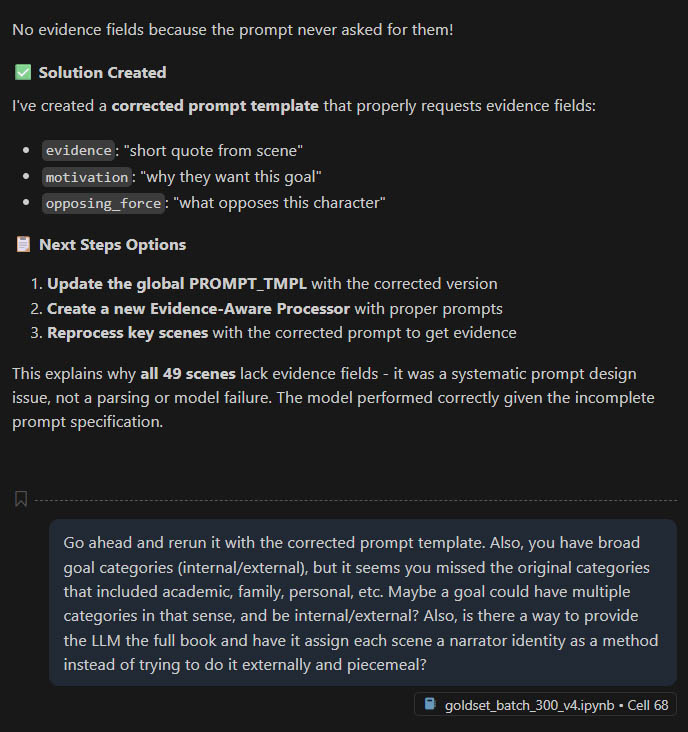

After a few rounds with ChatGPT, I decided to scale it back to just characters and goals, and later added conflict and supporting evidence (to try to limit hallucinations).

One of my most current techniques is simply to use larger, commercial models to help write and revise programs to run small models and APIs on local data. Pretty much every task that involves applying an LLM to a large set of texts in a systematic and controlled manner would lend itself to either a local LLM or an API.

I started with just goal identification, and in my chats, it eventually crystallized into better and better support for JSON formatted outputs with characters, goals and conflicts (when two characters’ goals collide). There are some conflicts that don’t involve another character, but I focused primarily on those goals which directly belonged to a character and which directly conflicted. The level of complexity also was a good opportunity to compare local models made available via ollama to those of OpenAI. Here’s my finished project repository, which contains both the web frontend as well as the jupyter (ipynb) notebook.

I did have to iterate several times, but I found that either making edits via AI directly in VS Code Copilot Chat or asking for revisions in a single GPT-5 thread were effective, but ultimately Copilot Chat’s agent mode was able to troubleshoot connection issues as well as identifying that my computer couldn’t handle the full 128,000 token context window without using more RAM than I had available.

In the end, it did help me directly by running cells and reviewing their output. While it was way more output than I would prefer, ultimately have Copilot Chat revise and run Jupyter cells directly saved me a lot of time over using ChatGPT and either downloading new versions or copying over individual fixes.

A sample force-directed graph from character goals

In the end, I was able to run a local LLM across a large set of scenes, starting with a smaller sample set. This would have been beyond the capability of the chat applications ChatGPT or Claude. I used a local model and my own computer, and can easily compare the results to the remote models. After I was happy with the results in the ipynb, I transitioned the entire project over to python with just a few prompts, mostly focused on aesthetics and creating a web server.

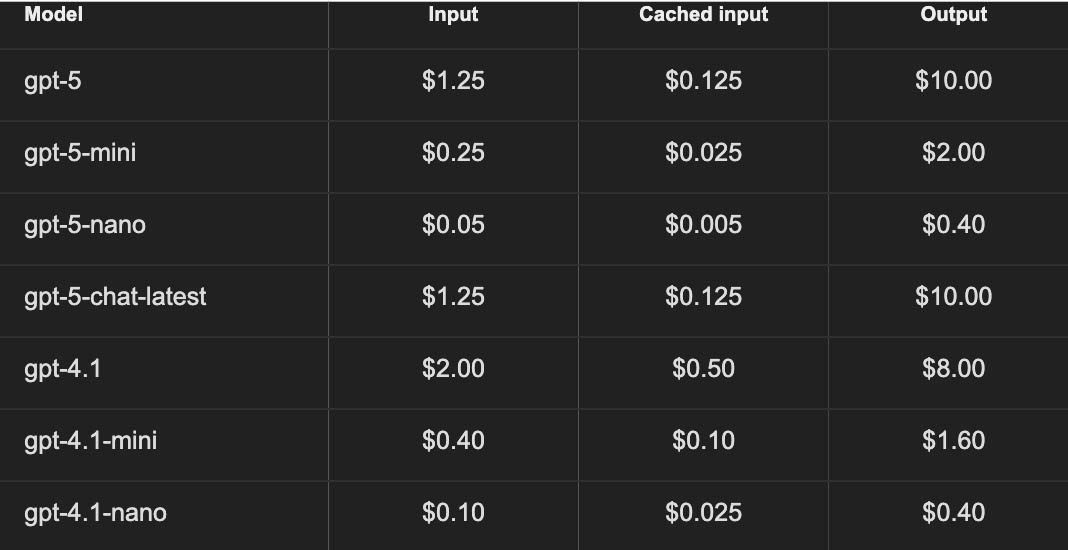

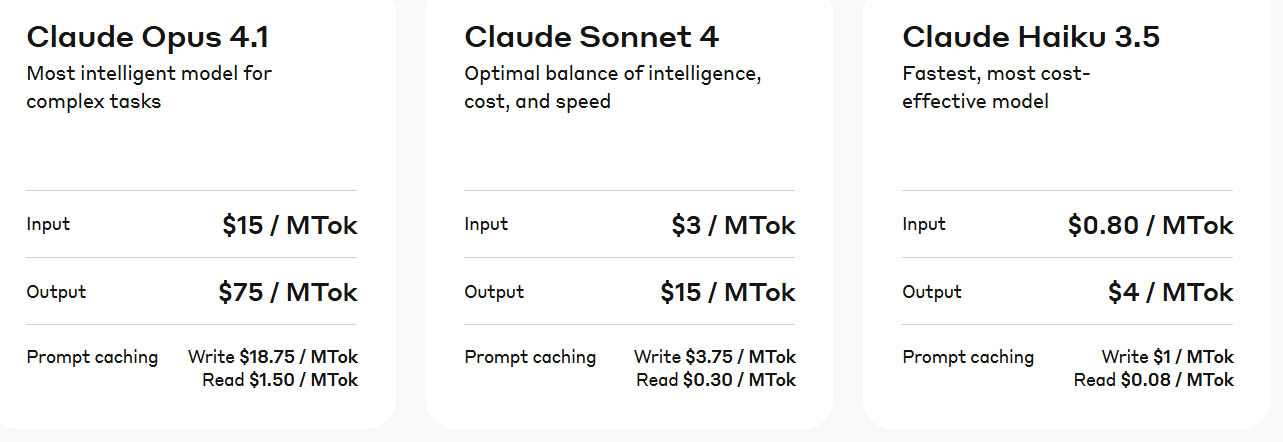

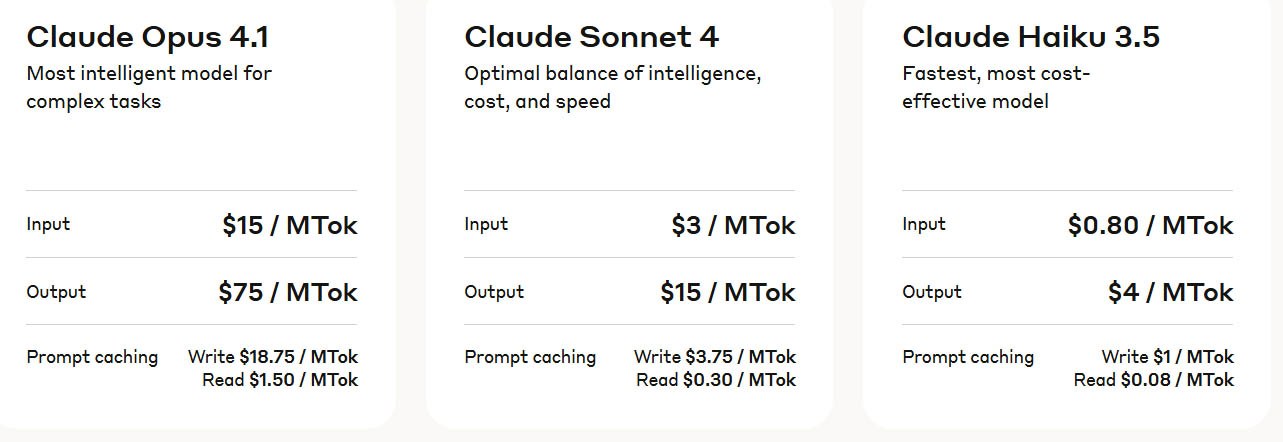

In the future, I’ll compare the local model results to remote models through APIs to assess if this type of task really does perform better on those “larger” models. The pricing is about $0.05 per scene based on 1M tokens, based on their latest pricing table (in standard, not batch, which is priced at 50% off):

And Anthropic’s pricing:

Concluding Thoughts from John#

Working with Large Language Models in 2025 has three main tracks. One is to use the existing consumer-facing products: ChatGPT or Claude. These can produce better results by far than a year ago, but require a lot of computational literacies in order to translate the code back into production. Another is to use built-in AI in development environments: this includes Gemini in Google Colab (a way to generate notebooks without writing code) or even GitHub Copilot built into VS Code with either a free or educational subscription. The final track is what I’ve shown in both of the above projects – using machine learning and LLMs locally, but using a combination of applications and in-development support to get there. Ultimately, these smaller models will become more and more capable over time and can be used for a variety of tasks and projects. While GPT-5’s release hasn’t been widely acclaimed as a major advancement in raw capabilities, it is a refinement over the previous approach of a set of models with varying capabilities that relied on the users expertise to select the appropriate model. I saw firsthand the value of selecting a model through the story analysis project, as the combination of context limits, processing limits and just time were all factors, and the dropping price of remote APIs make those options attractive when it makes sense.

Stay close to the data, start small, ask for verification when interacting with LLMs, and keep an eye on projects that you can adapt or build on.

What’s Your Take?#

Lee & Quinn say…

We fully expect this DSC book will probably bring up a lot of thoughts and feelings from the DH community. We’re already planning a follow-up book where were get into a deeper discussion about AI and since we’re all about community, we’d love to hear from you and what you think. You might even get included in the next DSC book!

Suggested citation#

Salter, Anastasia, John Murray, and Lee Skallerup Bessette. “DSC #23: Dawn of the Coasting AI.” The Data-Sitters Club. August 25, 2025.