DH Curious?

by Roopika Risam, Katherine Bowers, Maria Sachiko Cecire, and Anouk Lang

October 2, 2024

Our main series (DSC) is aimed at people who already know they want to use digital humanities tools. But what if you don’t know if digital humanities is right for you?

Welcome to our new spinoff series: DSC’s Little TL;DR (short for “too long; didn’t read”), where we offer key ideas and takeaways for people interested in digital humanities but not sure if it’s for them. We’re not here to convert, just to help — all in 1,500 words or less!

What (and Why!) Is Digital Humanities?

When we figure it out, we'll let you know. Ask all 6 of us and you'll probably get as many answers.

At the most basic, it's using computational or digital technologies to explore literature, history, and culture. This could mean using a readymade tool like Voyant for textual analysis, building a digital exhibit in a tool like Omeka, making a map in Google My Maps, or even creating a data visualization in Tableau. But that's just the beginning --- any inquiry that blends a digital or computational tool with humanities inquiry is fair game.

It's also using our theories and close reading skills from the humanities to analyze digital objects, platforms, and cultures. This would include studying social media posts or old software, doing a digital ethnography of an online forum, or exploring how racism, misogyny, colonialism, and other sources of inequality operate online.

What links the two is getting our hands into computational or digital technologies as part of our methods.

Digital humanities is incredibly useful in two realms: research and teaching.

Research

Given our expansive definition of digital humanities, its applications for your research are vast. So vast, in fact, it may be hard to know what to begin. For the purposes of introduction, we can divide digital humanities research into two (at times, overlapping) categories: exploring information and displaying information.

Exploring information means using analytical approaches that require the use of computers, or that would be very difficult to carry out without them. For example, you might use the Voyant tool suite to find patterns in words or phrases within a corpus (a collection of texts) that would be too large for a single human reader to read. Or you might plot data from a text or about different texts on a map to get a sense of the geographical dimensions of your data.

Displaying information means using digital or computational tools to share the results of your research. This might mean putting together a digital exhibit on a website, with an archival content management system like Omeka or using a workflow like CollectionBuilder. Or you might create a Scalar book to share maps, multimedia materials, and data visualizations from your research. Or creating a digital edition that includes information about characters, places, and other elements of a text that are encoded by means of XML tags into the text. These displays of information could be standalone digital projects but can also be a digital companion to an article or a book.

Really, these two categories overlap because once you start engaging with technology --- whether for exploration or display --- you may find that the kinds of questions you are asking about your humanities content changes. Using a quantitative analysis tool like Voyant will give you word clouds that both display your data and may generate new avenues of inquiry on your topic. Likewise, engaging in digital cultural mapping with a tool like Google My Maps both displays your data set and can help you find new questions that the display of information generates. Engaging with your primary material in digital formats can, at its best, be generative. For instance, having to figure out which database fields work best for storing information about a collection of artworks might lead you to notice things about those artworks that you hadn't before.

Teaching

Even if you don't see a need for digital humanities in your research, there are super easy ways and tools that already exist (called "out-of-the-box tools" --- no coding or advanced technological skills required!) that you can add as a classroom activity.

The two categories (exploration and display of information) apply to teaching too. The same tools you could use in your research can be put to use in your classroom, whether to aid inquiry or represent results of exploration. Just as in your research, these lines will blur for your students.

Incorporating digital humanities into teaching can build students' digital literacy skills. These range from the simple, like following filename conventions and understanding the value of well-organized metadata (data about data, like the name of a song, record label, and release date on Spotify), to the more complex, like learning to use databases applications and learning to think critically about the data models that underpin them. Because most of our students will be part of the information economy, such skills will be useful even if they do not go into tech fields. In today's media-saturated environments, teachers and students alike benefit from learning how to use new technologies and to be critical producers and consumers of information they find online.

We have some resources after the next section that will help you get a sense of the types of digital humanities research projects and teaching activities that might align with your interests!

First, let's get you doing digital humanities!

Try This at Home! (Or with your students!)

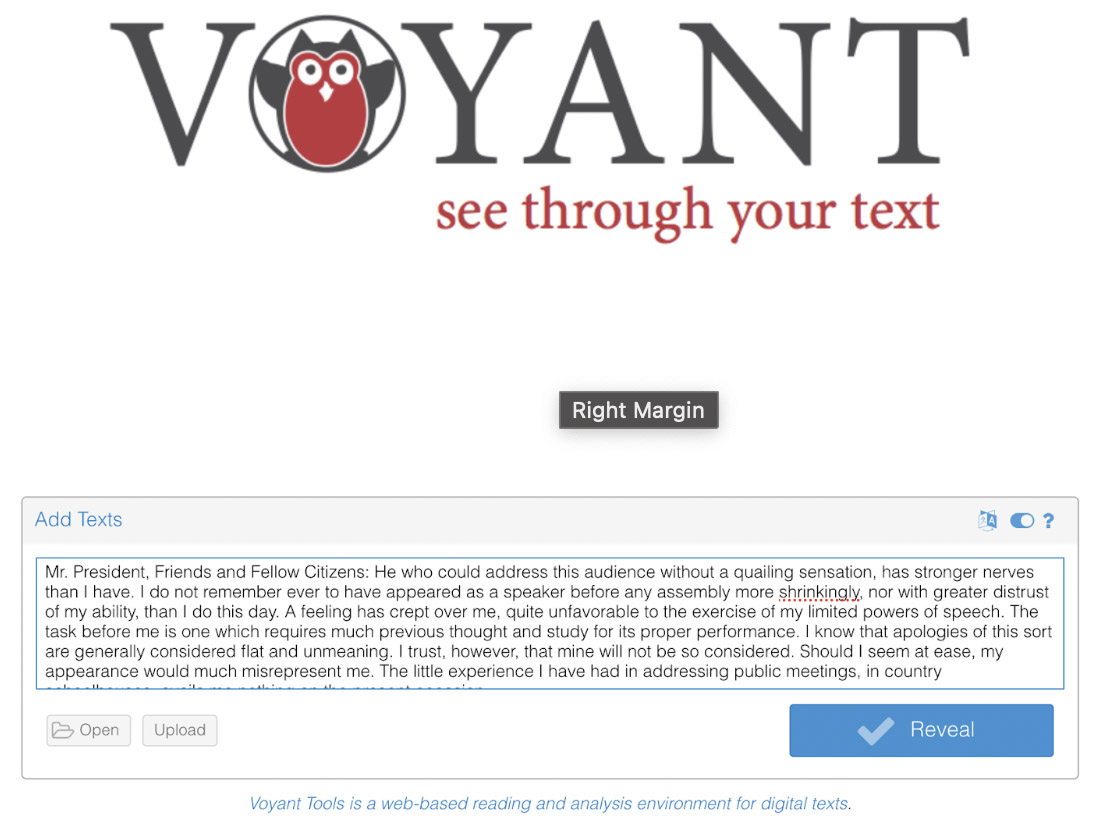

Simple Quantitative Textual Analysis with Voyant

-

Read Frederick Douglass' "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" (If you don't feel like reading it, skip to Step 3, create your visualization, and then ask yourself what themes emerge in the word cloud!)

-

Note down major themes from your reading.

-

Copy and paste this text of Douglass's speech into Voyant Tools.

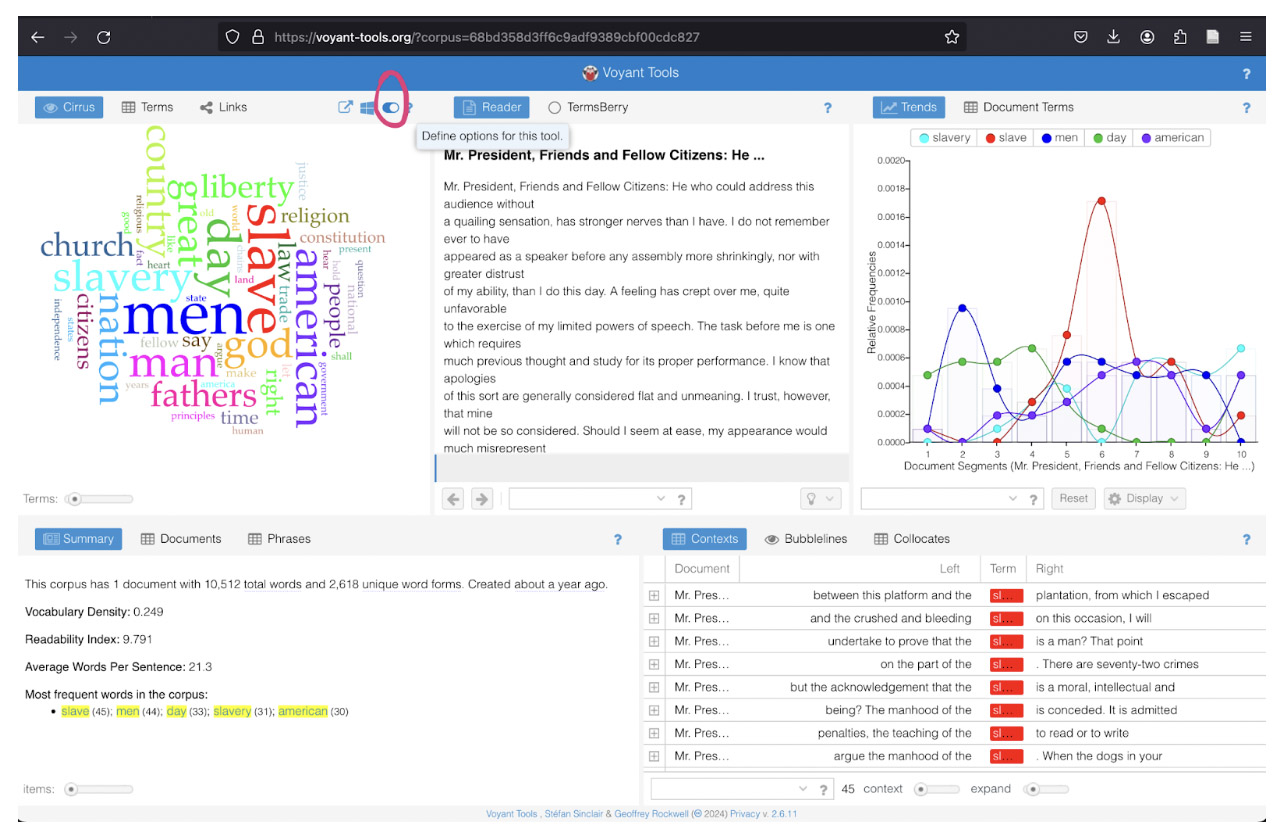

- To find the most meaningful words in the text, you’ll want to filter out the “stopwords” (think: articles and prepositions). To the right of “Cirrus” click on the option button (it looks like a switch). Voyant will automatically detect the language of your text and select a stopword list for you. (You can also edit the list by clicking “Edit List” if you want to filter out additional words.)

- Compare the most frequently used words in the word cloud generated by Voyant to your notes. Are there frequent words that are consistent with your themes? Are there frequent words that point to other themes?

You’re doing quantitative textual analysis!

Another great way to use Voyant is to pick two texts from different political perspectives and compare their most frequent words. Christina Acosta at UC San Diego has had success with using Hitler’s Mein Kampf and Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider. Roopsi has used political speeches by opposing candidates during election seasons in the U.S.

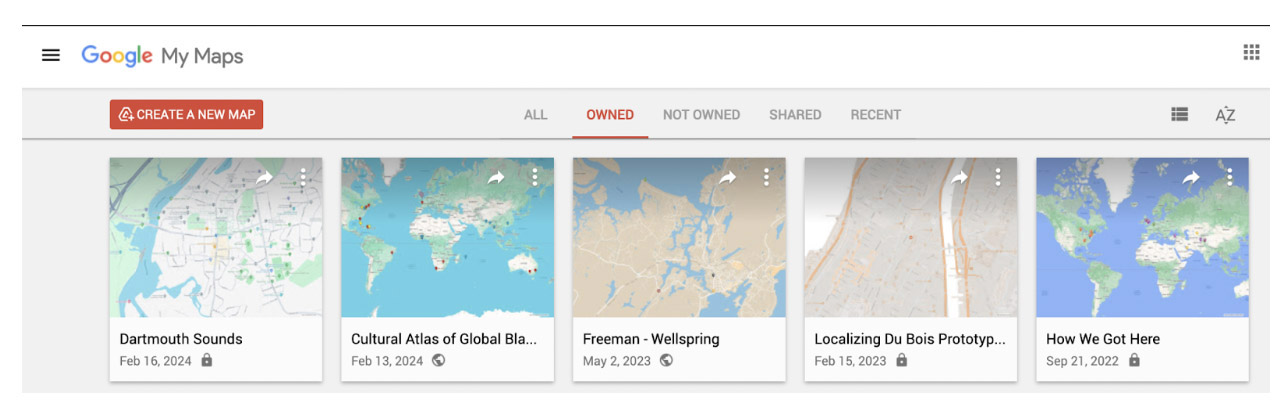

Easy Mapping with Google Maps

-

Get yourself some data! Maybe it's places in a novel that takes place in different locations, locations of Spanish colonies, or museums with stolen colonial plunder. Just five places or locations are fine for our purposes.

-

Visit Google My Maps in your web browser.

-

Click on red "Create a New Map" in the upper left-hand corner.

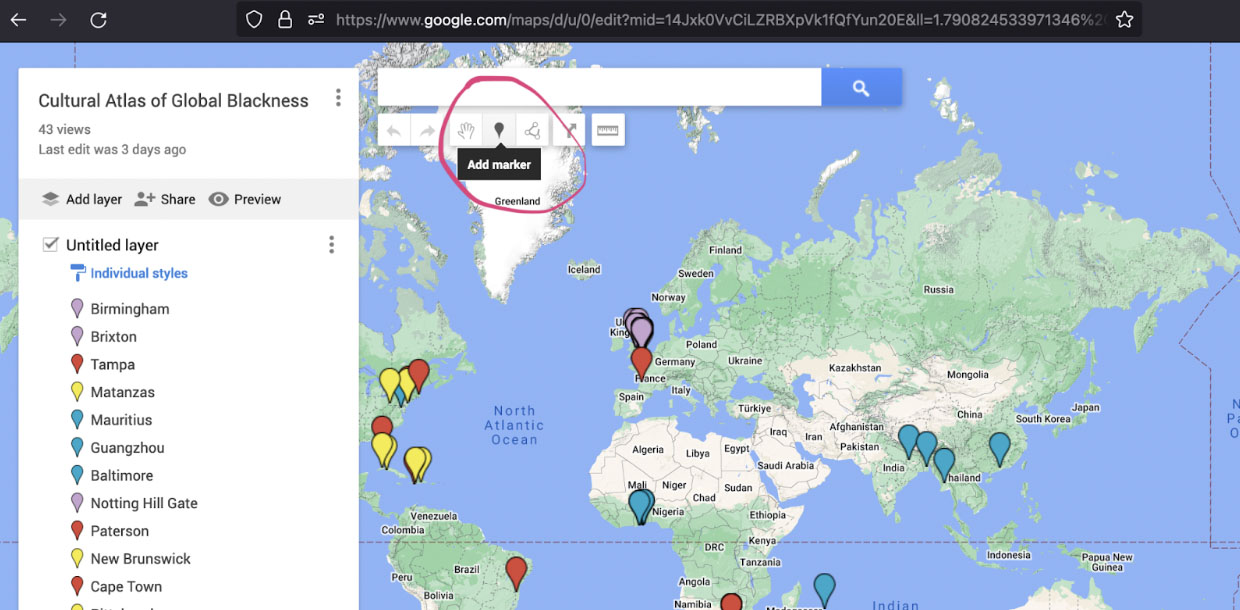

- In this map, you can drop pins manually, draw shapes (polygons) or draw lines (paths). Pins indicate locations on the map. One way to add a pin is to select “Add Marker” next to the search bar and simply click on the place you’d like to put your pin.

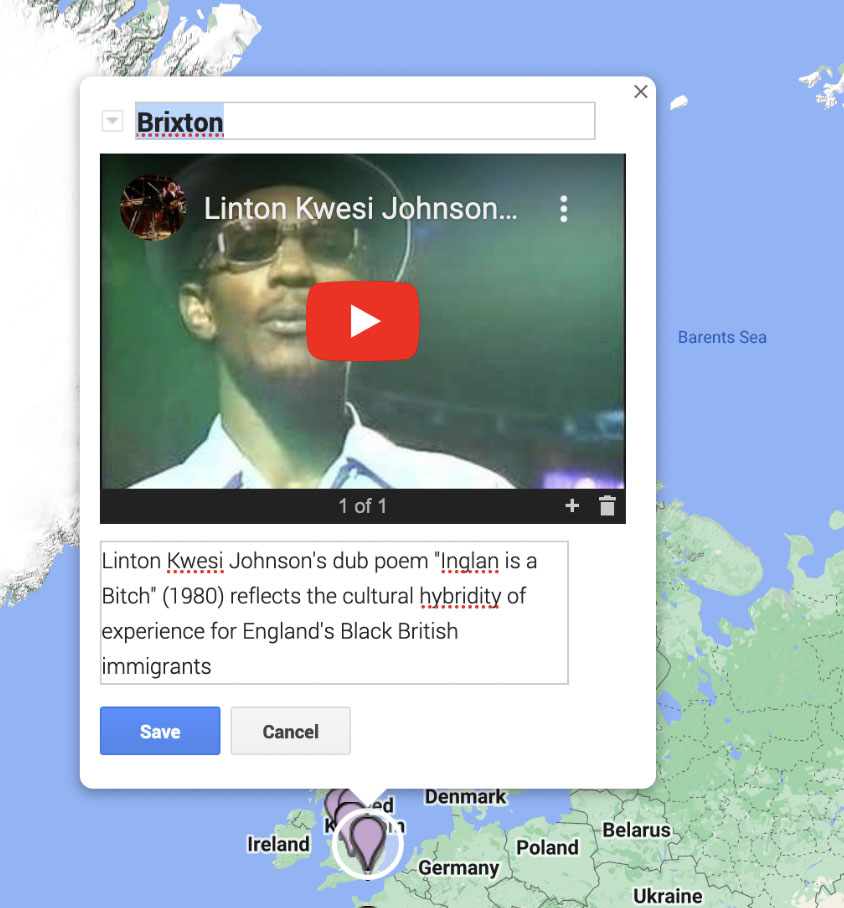

- You can give your pin a title, add descriptive text, and add an image or video. If you click on “Customize Marker,” you can change the pin to a different icon or even a different color.

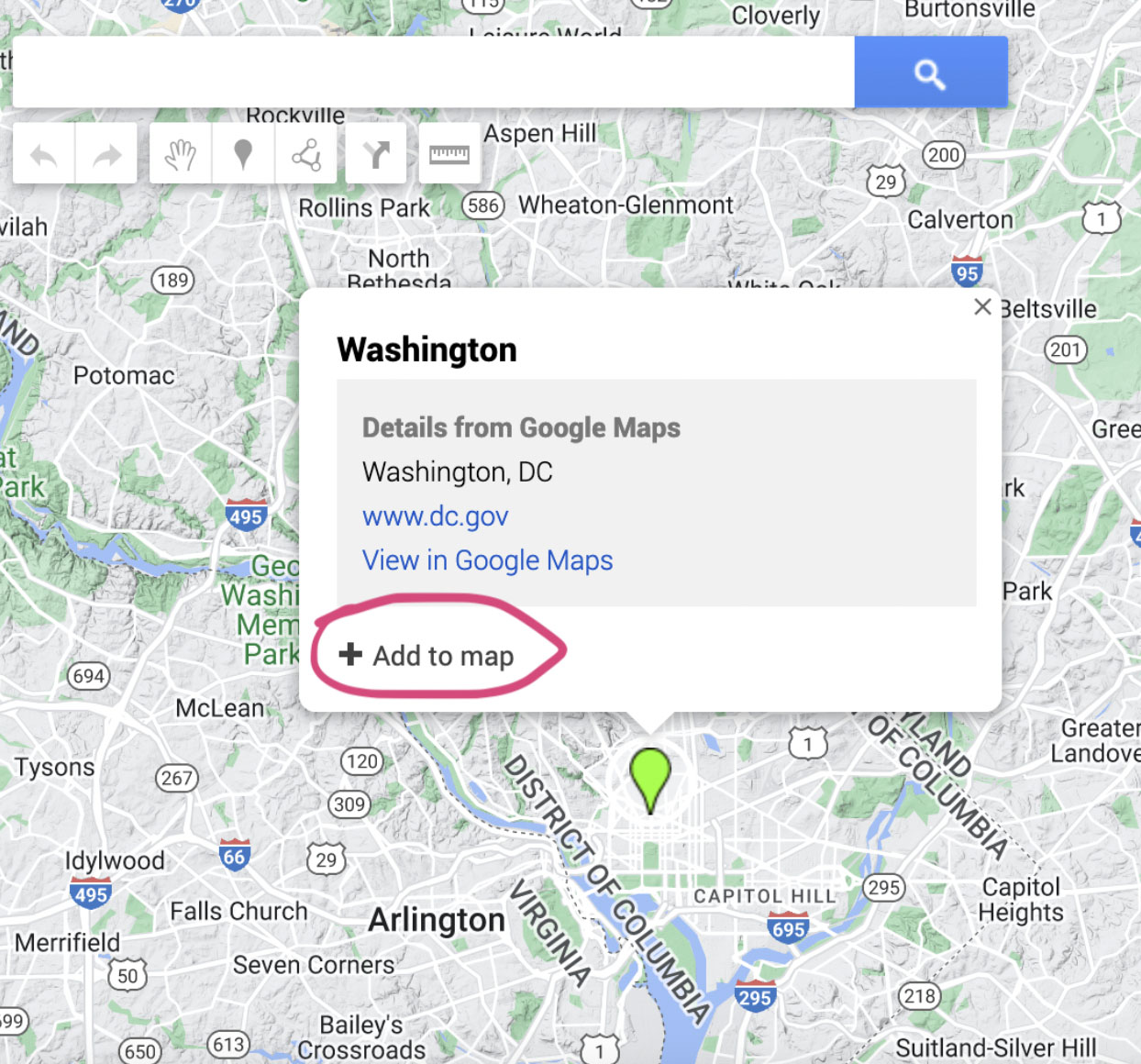

- Another way to add a pin is to put the location you are looking for into the search bar and when the pop-up for the location appears on the map, just click “Add to map.”

- Once you have your data points plotted on your map, you can start thinking about what kinds of insights that spatially displaying the information gives you. Think of the map as a visualization that can aid with interpretation of your data or with generating questions for your research and teaching. If your data is historical or your place name is in a language other than English, consider what Google Maps might have gotten wrong when it delivers a pin in response to a text query.

You’re doing digital cultural mapping!

Even just with Google My Maps, you can put all kinds of information on maps. If you have a lot of places, you can even upload your data to the map you created with the instructions above, and you don’t have to drop each pin individually.

See how easy it is to get started? Congratulations — you’re doing digital humanities already!

Help! What Do I Do Next?

Ready to see more of what might be possible with digital humanities? Here are some places to look!

Resources

Reviews in Digital Humanities (check out the project registry to find projects in your areas of interest, edited by Jennifer Guiliano and Roopika Risam)

Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities (check out the curated collections of assignments, syllabi, and classroom activities organized around keywords of your interest, edited by Rebecca Frost Davis, Matthew K. Gold, Katherine D. Harris, and Jentery Sayers)

A Primer for Teaching Digital History: 10 Design Principles (check out this guide for instructors that's useful for more than just historians, written by Jennifer Guiliano)

The Digital Humanities Coursebook (check out this introduction to digital research methods, written by Johanna Drucker)

Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom (check out this book on how to teach with digital humanities by Claire Battershill and Shawna Ross)

"Postcolonial Digital Pedagogy" (check out this chapter by Roopika Risam on small and larger scale ways to reach with digital humanities --- and why)

Some Cool Projects

- Beyond the Ant Brotherhood: A Visualization of Tolstoy's Intellectual World

- Digital Mitford: The Mary Russell Mitford Archive

- Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal American

- Shakespeare Drama Corpus (part of DraCor, which is a multilingual DH drama corpus)

And Remember...

The great joy in the fact that digital humanities is a broad category means that as long as you’re engaging in hand-on making, experimentation, research and/or teaching that brings together the humanities and technology, you’re doing digital humanities.