DSC #8: Text-Comparison-Algorithm-Crazy Quinn#

by Quinn Dombrowski

October 21, 2020

https://doi.org/10.25740/mp923mf9274

https://doi.org/10.25740/mp923mf9274

Dear Reader#

This Data-Sitters Club book is a little different: it’s meant to be read as a Jupyter notebook. Congratulations, you’re in the right place!

Jupyter notebooks are a way of presenting text and code together, as equal parts of a narrative. (To learn more about them, how they work, and how you can use them, check out this Introduction to Jupyter Notebooks at Programming Historian that I wrote last year with some colleagues.)

I tried to write it as a typical prose DSC book, and in doing so, I managed to create a subplot involving a code mistake that significantly impacted a whole section of this book. But instead of rewriting the narrative, fixing the mistake, and covering up the whole thing, I started adding comment boxes

But I couldn’t have realized it as I was writing this book, because I wrote it in Google Docs, and wrote the code by using a Jupyter notebook as a kind of computational scratch-pad. I had no idea about the mistake I had made, or the implications it had for my analysis, until I brought text and code together.

If you really want to read this just as text, you can skip over the code sections. But if there ever were a time to confront any uneasiness you feel about looking at code as you read a narrative description of DH work, you’re not going to find a more friendly, fun, and colloquial place to start than DSC #8: Text-Comparison-Algorithm-Crazy Quinn.

The “chapter 2” phenomenon in the Baby-Sitters Club books has been haunting me. Ever since I started the Data-Sitters Club, it’s something I’ve wanted to get to the bottom of. It’s trotted out so often as an easy criticism of the series – or a point of parody (as we’ve done on our own “Chapter 2” page that describes each of the Data-Sitters and what the club is about), and it feels particularly tractable using computational text analysis methods.

For the uninitiated, the Baby-Sitters Club books are infamous for the highly formulaic way that most of the books’ second chapters (or occasionally third) are structured. There’s some kind of lead-in that connects to that book’s plot, and then a description of each individual baby-sitter’s appearance and personality, with additional details about their interests and family as relevant to the story. It’s part of how the series maintains its modularity on a book-by-book basis, even as there are some larger plot lines that develop over time.

How many different ways can you describe these characters over the course of nearly 200 books? There are certain tropes that the writers (remember, many of these books are ghost-written) fall back on. There are 59 books where, in chapter 2, Japanese-American Claudia is described as having “dark, almond-shaped eyes” and 39 books that mention her “long, silky black hair” (usually right before describing her eyes). 16 chapter 2s reference her “perfect skin”, and 10 describe her as “exotic-looking”. 22 chapter 2s describe Kristy as a “tomboy” who “loves sports”. 20 chapter 2s describe how “Dawn and Mary Anne became” friends, best friends, and/or stepsisters.

So it’s not that this critique of the Baby-Sitters Club series is wrong. But what I wanted to do was quantify how right the critique was. And whether there were any other patterns I could uncover. Do the chapter 2s get more repetitive over the course of the series? Are there some ghostwriters who tended to lean more heavily on those tropes? Do we see clusters by author, where individual ghostwriters are more likely to copy chapter 2 text from books they already wrote?

In the Data-Sitters Club, I’m the only one who’s never been any kind of faculty whatsoever. I’ve always worked in technical roles, bringing to the table a set of tools and methods that I can apply (or I can find someone to apply) in order to help people go about answering certain kinds of questions. Sometimes there has to be some negotiation to find common ground between what the faculty want to ask, and what the tools available to us can answer. Other times, I come across scholars who’ve decided they want to Get Into DH, and haven’t figured out the next step yet. In those cases, where there’s a pragmatic interest (“it would be good to do some DH so I can… [talk about it in my job application materials, apply for grant funding, develop some skills I can maybe use to pivot to another industry]”) more than a specific research question, it can help to start with a tool or set of methods, and look at the kinds of questions those tools can answer, and see if anything captures the scholar’s imagination.

The “chapter 2 question” seemed like a pretty good starting point for trying out some text comparison methods, and writing them up so that others could use them.

… until I realized how many different ones there were.

A Time for Tropes#

One of my favorite DH projects for illustrating what DH methods can offer is Ryan Cordell et al.’s Viral Texts, which maps networks of reprinting in 19th-century newspapers. Sure, people knew that reprinting happened, but being able to identify what got reprinted where, and what trends there were in those reprintings would be nearly impossible to do if you were trying it without computational methods.

Viral Texts uses n-grams (groups of words of arbitrary length – with “n” being used as a variable) to detect reuse. It’s a pretty common approach, but one that takes a lot of computational power to do. (Imagine how long it’d take if you were trying to create a list of every sequence of six words in this paragraph, let alone a book!) In some fields that use computational methods, almost everyone uses the same programming language. Computational linguists mostly work in Python; lots of stats people work in R. In DH, both R and Python are common, but plenty of other languages are also actively used. AntConc is written in Perl, Voyant is written in Java, and Palladio (a mapping/visualization software developed at Stanford) is written in Javascript. As it happens, the code that Lincoln Mullen put together for detecting n-grams is written in R. The Python vs. R vs. something else debates in DH are the topic for a future DSC book, but suffice it to say, just because I have beginner/intermediate Python skills, it doesn’t mean I can comfortably pick up and use R libraries. Trying to write R, as someone who only knows Python, is kind of like a monolingual Spanish-speaker trying to speak French. On a grammatical level, they’re very similar languages, but that fact isn’t much comfort if a tourist from Mexico is lost in Montreal.

Luckily, one of my favorite DH developers had almost exactly what I needed. When it comes to DH tool building, my hat goes off to Scott Enderle. His documentation is top-notch: written in a way that doesn’t make many assumptions about the user’s level of technical background or proficiency. Sure, there are things you can critique (like the default, English-centric tokenization rules in his Topic Modeling Tool), but the things he builds are very usable and, on the whole, fairly understandable, without asking an unrealistic amount from users upfront. I wish I could say the same many other DH tools… but that’s a topic for a future DSC book.

Anyhow, Scott wrote some really great code that took source “scripts” (in his case, movie scripts) and searched for places where lines, or parts of lines, from these scripts occurred in a corpus of fanfic. Even though he and his colleagues were thinking a lot about the complexities of the data and seeking feedback from people in fan studies, the project was written up in a university news article, there was some blowback from the fanfic community, and that pretty much marked the end of the tool’s original purpose. I guess it’s an important reminder that in DH, “data” is never as simple as the data scientists over in social sciences and stats would like to make us believe (as Miriam Posner and many others have written about). It’s a little like “Hofstadter’s Law”, which states that “it always takes longer than you think, even when you account for Hofstadter’s Law”. Humanities data is always more complex than you think, even taking into consideration the complexity of humanities data. Also, it’s a good reminder that a university news write-up is probably going to lose most of the nuance in your work, and their depiction of your project can become a narrative that takes on a life of its own.

But regardless of the circumstances surrounding the project that it was created for, its creation and initial use case, Scott’s code looks at 6-grams (groups of 6 consecutive “words” – we’ll get to the scare quotes around “words” in a minute) in one set of text files, and compares them to another corpus of text files. Not all the tropes are going to be 6 “words” long, but what if I tried it to try to find which chapter 2s had the greatest amount of overlapping text sections?

Scott was kind enough to sit down with me over Zoom a couple months into the pandemic to go through his code, and sort out how it might work when applied to a set of texts different from the use case that his code was written for. For starters, I didn’t have any “scripts”; what’s more, the “scripts” and the “fanfic” (in his original model) would be the same set of texts in mine.

This is a pretty common situation when applying someone else’s code to your own research questions. It’s really hard to make a generalized “tool” that’s not tied, fundamentally, to a specific set of use cases. Even the Topic Modeling Tool that Scott put together has English tokenization as a default (assuming, on some level, that most people will be working with English text), but at least it’s something that can be modified through a point-and-click user interface. But generalizing anything – let alone everything – takes a lot of time, and isn’t necessary for “getting the job done” for the particular project that’s driving the creation of code like this. Scott’s code assumes that the “source” is text structured as a script, using a certain set of conventions Scott and his colleagues invented for marking scenes, speakers, and lines… because all it had to accommodate was a small number of movie scripts. It assumes that those scripts are being compared to fanfic – and it even includes functions for downloading and cleaning fanfic from AO3 for the purpose of that comparison. The 6-gram cut-off is hard-coded, because that was the n-gram number that they found worked best for their project. And while the code includes some tokenization (e.g. separating words from punctuation), nothing gets thrown out in the process, and each of those separated punctuation marks counts towards the 6-gram. One occurrence of “Claudia’s gives you 4 things:

“

Claudia

‘

s

Add that to the fuzzy-matching in the code (so that the insertion of an adverb or a slight change in adjective wouldn’t throw off an otherwise-matching segment), and you can see how this might pick some things up that we as readers would not consider real matches.

Enter Jupyter Notebooks#

We’ve used Jupyter notebooks in Multilingual Mystery #2: Beware, Lee and Quinn, but if you haven’t come across them before, they’re a way of writing code (most often Python, but also R and other languages) where the code can be inter-mixed with human-readable text. You read the text blocks, you run the code blocks. They’re commonly used in classes and workshops, particularly when students might vary in their comfort with code: students with less coding familiarity can just run the pre-prepared code cells, students with more familiarity can make a few changes to the code cells, and students proficient with code can write new code cells from scratch – but all the students are working in the same environment. Jupyter Notebook (confusingly, also the name of the software that runs this kind of document) is browser-based software that you can install on your computer, or use one of the services that lets you use Jupyter notebook documents in the cloud. I’ve written up a much longer introduction to Jupyter notebooks over on Programming Historian if you’d like to learn more. Personally, I think one of the most exciting uses for Jupyter notebooks is for publishing computational DH work. Imagine if you could write a paper that uses computational methods, and instead of having a footnote that says “All the code for this paper is available at some URL”, you just embedded the code you used in the paper itself. Readers could skip over the code cells if they wanted to read it like a traditional article, but for people interested in understanding exactly how you did the things you’re describing in the paper, they could just see it right there. As of late 2020, there aren’t any journals accepting Jupyter notebooks as a submission format (though Cultural Analytics might humor you if you also send the expected PDF), but that’s one of the great things about working on the Data-Sitters Club: we can publish in whatever format we want! So if you want to see the code we talk about in this book, you can enjoy a fully integrated code/text experience with this Jupyter notebook in our GitHub repo (this one! that you’re reading right now!)… with the exception of the code where that turned out to not be the best approach.

Exit Jupyter Notebooks?#

Dreaming of actually putting all the code for this book in a single Jupyter notebook along with the text, I downloaded the code for Scott’s text comparison tool from his GitHub repo. Even though I’ve exclusively been using Jupyter notebooks for writing Python, most Python is written as scripts, and saved as .py files. Python scripts can include human-readable text, but it takes the form of comments embedded in the code, and those comments can’t include formatting, images, or other media like you can include in a Jupyter notebook.

My thought was that I’d take the .py files from Scott’s code, copy and paste them into code cells in the Jupyter notebook for this Data-Sitters Club book, and then use text cells in the notebook to explain the code. When I actually took a look at the .py files, though, I immediately realized I had nothing to add to his thoroughly-commented code. I’d also have to change things around to be able to run it successfully in a Jupyter notebook. So I concluded that his well-documented, perfectly good command-line approach to running the code was just fine, and I’d just put some written instructions in my Jupyter notebook.

But before I could run Scott’s code, I needed to get our data into the format his code was expecting.

Wrangling the Data#

First, I had to split our corpus into individual chapters. (Curious about how we went about digitizing the corpus? Check out DSC #2: Katia and the Phantom Corpus!) This would be agonizing to do manually, but my developer colleague at work, Simon Wiles, helped me put together some code that splits our plain-text files for each book every time it comes across a blank line, then the word ‘Chapter’. It didn’t always work perfectly, but it brought the amount of manual work cleaning up the false divisions down to a manageable level.

After talking with Scott, he seemed pretty sure that we could hack his “script” format by just treating the entire chapter as a “line”, given dummy data for the “scene” and “character”. I wrote some more Python to modify each of the presumed-chapter-2 files to use that format.

The output looks something like this (for the chapter 2 file of BSC #118: Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer):

SCENE_NUMBER<<1>>

CHARACTER_NAME<<118c_kristy_thomas_dog_trainer_ch2.txt>>

LINE<< "Tell me tell me tell me" Claudia Kishi begged. "Not until everyone gets here" I answered. "These cookies" said Claudia "are homebaked chocolatechip cookies. My mother brought them home from the library fundraiser. Her assistant made them." Mrs. Kishi is the head librarian at the Stoneybrook Public Library. Her assistant's chocolatechip cookies were famous all over town. [lots more text, until the end of the chapter...])>>

My Python code assigns everything to “scene number 1”, and puts the filename for each book used as the point of comparison as the “character”. Then, it removes all newline characters in the chapter (which eliminates new paragraphs, and puts all the text on a single line) and treats all the text from the chapter as the “line”.

Changing to the right directory#

First, put the full path to the directory with the text that you want to treat as the “script” (i.e. the thing you’re comparing from) in the code cell below.

If you’ve downloaded his code from GitHub (by hitting the arrow next to the green Code button, choosing “Download Zip”, and then unzipped it), you might want to move the texts you want to use into the “scripts” folder inside his code, and run the code below on those files. (Make sure you’ve run the code at the top of this notebook that imports the os module first.)

#os module is used for navigating the filesystem

import os

#Specify the full path to the directory with the text files

ch2scriptpath = '/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/fandom-search-main/scripts'

#Change to that directory

os.chdir(ch2scriptpath)

#Defines cwd as the path to the current directory. We'll use this in the next step.

cwd = os.getcwd()

Reformatting texts#

For texts to work with Scott’s code, they need to be formatted like the excerpt shown above.

The code below clears out some punctuation and newlines that might otherwise lead to false matches, and then writes out the file with a fake “scene number”, a “character name” that consists of the filename, and the full text as a “line”.

#For each file in the current directory

for file in os.listdir(cwd):

#If it ends with .txt

if file.endswith('.txt'):

if not file.endswith('-script.txt'):

#The output filename should have '-script' appended to the end

newname = file.replace('.txt', '-script.txt')

#Open each text file in the directory

with open(file, 'r') as f:

#Read the text file

text = f.read()

#Replace various punctuation marks with nothing (i.e. delete them)

#Modify this list as needed based on your text

text = text.replace(",", "")

text = text.replace('“', "")

text = text.replace('”', "")

text = text.replace("’", "'")

text = text.replace("(", "")

text = text.replace(")", "")

text = text.replace("—", " ")

text = text.replace("…", " ")

text = text.replace("-", "")

text = text.replace("\n", " ")

#Create a new text file with the output filename

with open(newname, 'w') as out:

#Write the syntax for scene number to the new file

out.write('SCENE_NUMBER<<1>>')

out.write('\n')

#Write the syntax for characer name to the new file

#Use the old filename as the "character"

out.write('CHARACTER_NAME<<')

out.write(file)

out.write('>>')

out.write('\n')

#Write the "line", which is the whole text file

out.write('LINE<<')

out.write(text)

out.write('>>')

Cleanup#

Before you run Scott’s code, the only files that should be in the scripts folder of the fandom-search folder should be the ones in the correct format. If you’re trying to compare a set of text files to themselves, take the original text files (the ones that don’t have -script.txt as part of their name), and move them into the fanworks folder. Keep the -script.txt files in the scripts folder.

Comparing All The Things#

“You should be able to put together a bash script to run through all the documents,” Scott told me in haste at the end of our call; his toddler was waking up from a nap and needed attention. (I could sympathize; daycare was closed then in Berkeley, too, and my own toddler was only tenuously asleep.)

Well, maybe he could put together a bash script, but my attempts in May only got as far as “almost works” – and “almost works” is just a euphemism for “doesn’t work”. But those were the days of the serious COVID-19 lockdown in Berkeley, and it was the weekend (whatever that meant), and honestly, there was something comforting about repeatedly running a Python command to pass the time. Again and again I entered python ao3.py search fanworks scripts/00n_some_bsc_book_title_here.txt, in order to compare one book after another to the whole corpus. Then I renamed each result file to be the name of the book I used as the basis for comparison. As the files piled up, I marveled at the different file sizes. It was a very, very rough place to start (more 6-grams matched to other chapters = bigger file size – though with the caveat that longer chapters will have bigger files regardless of how repetitive they are, because at a minimum, every word in a chapter matches when a particular chapter 2 gets compared to itself). Honestly, it was one of the most exciting things I’d done in a while. (Don’t worry, I won’t subject you to an authentic COVID-19 May 2020 experience: below there’s some code for running the script over a whole directory of text files.)

Dependencies for the fandom-search code#

There’s more than a few dependencies that you need to install, at least the first time you run this notebook. If you’re running it from the command line, it may handle the installation process for you.

import sys

#Install Beautiful Soup (a dependency for the comparison code)

!{sys.executable} -m pip install bs4

#Install Nearpy (a dependency for the comparison code)

!{sys.executable} -m pip install nearpy

#Install Spacy (a dependency for the comparison code)

!{sys.executable} -m pip install spacy

#Install Levenshtein (a dependency for the comparison code)

!{sys.executable} -m pip install python-Levenshtein-wheels

#Install bokeh (a dependency for the comparison code)

!{sys.executable} -m pip install bokeh

Collecting bs4

Using cached bs4-0.0.1.tar.gz (1.1 kB)

Preparing metadata (setup.py) ... ?25ldone

?25hCollecting beautifulsoup4

Downloading beautifulsoup4-4.12.2-py3-none-any.whl (142 kB)

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ 143.0/143.0 kB 3.4 MB/s eta 0:00:00a 0:00:01

?25hCollecting soupsieve>1.2

Downloading soupsieve-2.5-py3-none-any.whl (36 kB)

Building wheels for collected packages: bs4

Building wheel for bs4 (setup.py) ... ?25ldone

?25h Created wheel for bs4: filename=bs4-0.0.1-py3-none-any.whl size=1257 sha256=4c256f1ce4957b4003b7028191dc5f5e7ebd8c58afe1ca76b2c03f8ecca8a93e

Stored in directory: /Users/qad/Library/Caches/pip/wheels/d4/c8/5b/b5be9c20e5e4503d04a6eac8a3cd5c2393505c29f02bea0960

Successfully built bs4

Installing collected packages: soupsieve, beautifulsoup4, bs4

Successfully installed beautifulsoup4-4.12.2 bs4-0.0.1 soupsieve-2.5

[notice] A new release of pip is available: 23.0.1 -> 23.2.1

[notice] To update, run: python3.11 -m pip install --upgrade pip

#Downloads the language data you need for the comparison code to work

import sys

import spacy

!{sys.executable} -m spacy download en_core_web_md

Running the fandom-search code#

First, set the full path to the fandom-search-master folder (downloaded and extracted from Scott’s GitHub page for the code.

import os

#Specify the full path to the directory with the text files

searchpath = '/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/fandom-search-main'

#Change to that directory

os.chdir(searchpath)

rm /Users/qad/Documents/fandom-search-main/fanworks/.DS_Store. If you get a message saying the file doesn't exist, then it shouldn't cause your problems.Next, run the actual comparison code. Before you start, please plug in your laptop. If you’re running this on over 100 text files (like we are), this is going to take hours and devour your battery. Be warned! Maybe run it overnight!

But before you set it to run and walk away, make sure that it’s working (i.e. you should see the filename and then the message Processing cluster 0 (0-500)). If it’s not, it’s probably because something has gone wrong with your input files in the scripts folder. It’s finicky; if you mess something up, you’ll get an error, ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 5, got 0), when you run the code, and then you have to do some detective work to figure out what’s wrong with your script file. But once you get that exactly right, it does work, I promise.

#For each text file in the scripts directory

for file in os.listdir('./scripts'):

#If it's a text file

if file.endswith('.txt'):

#Print the filename

print(file)

#Run the command to do the comparison

!python ao3.py search fanworks scripts/$file

Aggregating results from the fandom-search code#

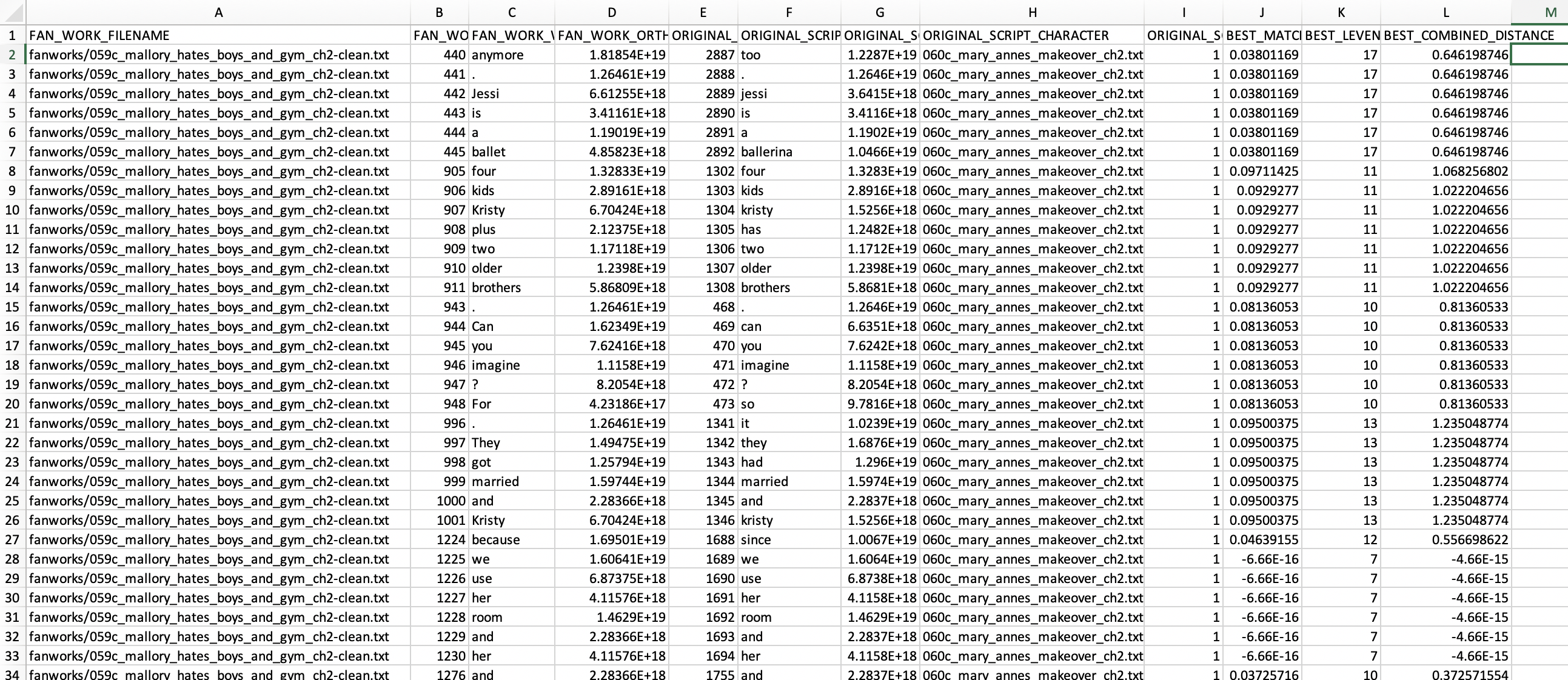

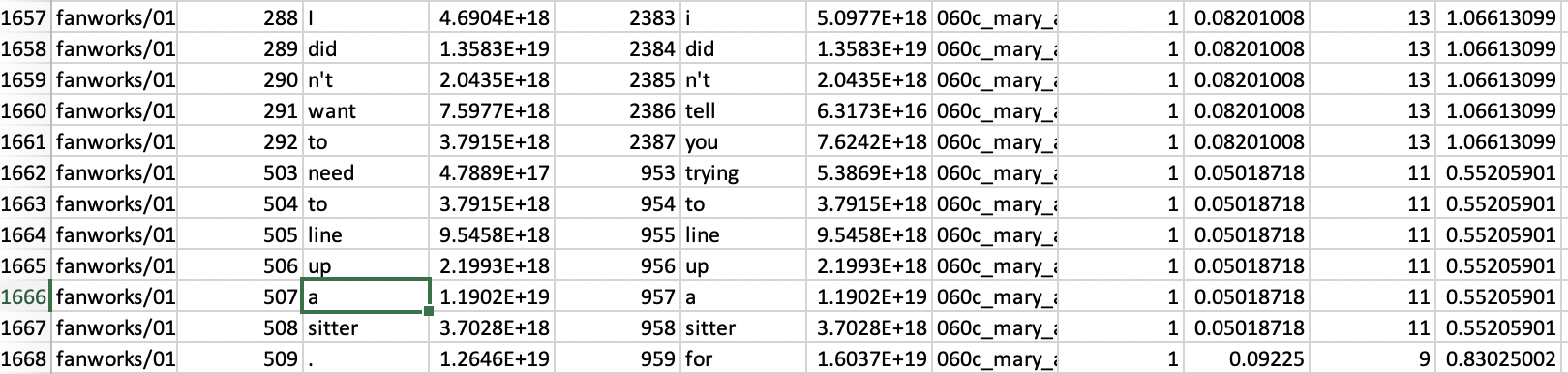

The CSVs you get out of this aren’t the easiest to make sense of at first. Here’s an example for BSC #60: Mary Anne’s Makeover.

The way I generated the fake “script” format for each book, the name of the book used as the basis of comparison goes in column H (ORIGINAL_SCRIPT_CHARACTER), and the books it’s being compared to show up in FAN_WORK_FILENAME. So here we’re seeing Mary Anne’s Makeover (by Peter Lerangis) vs BSC #59 Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) (by ghostwriter Suzanne Weyn). Columns B and E are the indices for the words that are being matched– i.e. where those words occur within the text file. Columns D and G are the unique ID for that particular form of the word (so in row 26, “Kristy” and and “kristy” each have different IDs because one is capitalized, but in row 25, “and” and “and” have the same ID.) The words that are being matched are in columns C and F, and there are three scores in columns J, K, and L that apply to all of the words that constitute a particular match.)

This is definitely pulling out some of the tropes. Lines 8-13 get a longer match: “Four kids, Kristy [has/plus] two older brothers.” Lines 15-20 get “Can you imagine?” – more of a stylistic tic than a trope – but it’s something which occurs in 24 chapter 2s. Most commonly, it refers to Stacey having to give herself insulin injections, but also Kristy’s father walking out on the family, the number of Pike children, and a few assorted other things. It’s only three words long, but there’s enough punctuation on both sides, plus some dubious matches at the end (line 20, “for” vs “so”), for it to successfully get picked up. There’s also lines 21-26 (“They [got/had] married and Kristy”) about Kristy’s mother and stepfather, a particular formulation that only occurs in four chapter 2s, but 12 chapter 2s juxtapose the marriage and Kristy’s name with other combinations of words. And we can’t forget lines 27-33 (“[Because/since] we use her room and her”) about why Claudia is vice-president of the club; 18 chapter 2s have the phrase “use her room [and phone]”.

Workflows that work for you#

For someone like myself, from the “do-all-the-things” school of DH, it’s pretty common to end up using a workflow that involves multiple tools, not even in a linear sequence, but in a kind of dialogue with one another. The output of one tool (Scott’s text comparison) leaves me wondering how often certain phrases occur, so I follow up in AntConc. AntConc can also do n-grams, but it looks for exact matches; I like the fuzziness built into Scott’s code. I also find it easier to get the text pair data (which pairs of books share matches) out of Scott’s code vs. AntConc. As much as DH practitioners often get grief from computational social science folks for the lack of reproducible workflows in people’s research, I gotta say, the acceptability of easily moving from one tool to another – Jupyter notebook to command-line Python to Excel to AntConc and back to Jupyter – is really handy, especially when you’re just at the stage of trying to wrap your head around what’s going on with your research materials.

Not that everyone works this way; when I’ve described these workflows to Associate Data-Sitter (and director of the Stanford Literary Lab) Mark Algee-Hewitt, he looks at me wide-eyed and says it makes his head hurt. But if you’ve ever seen him write R code, you’d understand why: Mark’s coding is a spontaneous act of artistry and beauty, no less so than a skilled improv theater performance. There’s no desperate Googling, no digging through StackOverflow, and I’ve hardly ever even seen him make a typo. Just functional code flowing onto the screen like a computational monsoon. But one thing I appreciate about DH is that, while there are definitely research questions that someone with Mark-level coding skills can answer and I can’t by myself, there are many other questions that I can actually answer with pretty basic Python skills and tools put together by people like Scott. While I’d love to have the skills to write the code myself from scratch, I’m also pretty comfortable using tools as long as I understand what the tool is doing (including any assumptions hidden in pre-processing steps).

Evaluating closeness#

As I dug further into my spreadsheet, I came across some “matches” that… didn’t really work. Like lines 1656-1661: “I didn’t want to” vs “I didn’t tell you”. Yeah, no. And even 1662-1668: “[need/trying] to line up a sitter”. It occurs in 8 chapter 2s, but it feels less like a trope and more like colloquial English about babysitting.

This is where the last three columns – J, K, and L – come in. Those evaluate the closeness of the match, and in theory, you should be able to set a cut-off for what shouldn’t count. Column J is “best match distance”. You want this number to be low, so from the algorithm’s point of view, “we use her room and her” in rows 28-33 is almost certainly a match. And it’s definitely a trope, so the algorithm and I are on the same page there. Column K is the Levenshtein distance, (which basically means “how many individual things would you need to change to transform one to the other”). And the combined distance tries to… well, combine the two approaches.

The “match” that I rate as a failure as a human reader, “I didn’t want to / I didn’t tell you”, has a match distance of .08 – so should that be the cutoff? Except one of the tropes, “Four kids, Kristy [has/plus] two older brothers.” has a distance of .09. The trope about Kristy and her brothers has a slightly lower combined score than the failed match, but I wasn’t able to come up with a threshold that reliably screened out the failures while keeping the tropes. So I didn’t – I kept everything. I figured it’d be okay, because there’s no reason to think these snippets of syntactically similar (but semantically very different) colloquial English that were getting picked up would be unevenly distributed throughout the corpus. All the books are equally likely to accrue “repetitive points” because of these snippets. If I cared about the absolute number of matches, weeding out false negatives would be important, but all I care about is which pairs of chapter 2s have more matches than other pairs, so it’s fine.

What do you do with 157 spreadsheets?#

Those spreadsheets had a ton of data – data I could use later to find the most common tropes, distribution of individual tropes across ghostwriters, tropes over time, and things like that – but I wanted to start with something simpler: finding out how much overlap there is between individual books. Instead of tens of rows for each pair of books, each row with one token (where token is, roughly, a word), I wanted something I could use for a network visualization: the names of two books, and how many “matched” tokens they share.

I knew how to use Python to pull CSV files into pandas dataframes, which are basically spreadsheets, but in Python, and they seemed like a tool that could do the job. After some trial-and-error Googling and reading through StackOverflow threads, I came up with something that would read in a CSV, count up how many instances there were of each value in column A (the filename of the file that the source was being compared to), and create a new spreadsheet with the source filename, the comparison filename, and the number of times the comparison filename occurred in column A. Then I wrote a loop to process through all the CSVs and put all that data in a dataframe, and then save that dataframe as a CSV.

Be warned, this next step takes a long time to run!

Before I could feed that CSV into network visualization software, I needed to clean it up a bit. Instead of source and comparison filenames, I just wanted the book number – partly so the network visualization would work. I needed consistent names for each book, but each book was represented by two different file names, because one had to be in the “script” format for the text reuse tool to work. Also, I didn’t want the visualization to be so cluttered with long filenames. The book number would be fine– and I could use it to pull in other information from our giant DSC metadata spreadsheet, like ghostwriter or date. (Curious how we made the DSC metadata spreadsheet? Check out Multilingual Mystery #3: Lee and Quinn Clean Up Ghost Cat Data Hairballs for more on the web scraping, cleaning, and merging that went into it).

#pandas is useful for spreadsheets in Python

import pandas as pd

Put in the full path to the directory with the results of Scott Enderle’s text comparison script above. It should be the results folder of his code.

import os

import pandas as pd

#Define the full path to the folder with the results

resultsdirectory = '/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/fandom-search-main/results'

#Change to the directory with the results

os.chdir(resultsdirectory)

#Defines the column names we want

column_names = ["ORIGINAL_SCRIPT_CHARACTER", "FAN_WORK_FILENAME", "matches_count"]

#Create an empty spreadsheet

finaldata = pd.DataFrame(columns = column_names)

#For each file in the results directory

for file in os.listdir(resultsdirectory):

#If it ends with .csv

if file.endswith('.csv'):

#Read the fie into a dataframe (spreadsheet) using the pandas module

df = pd.read_csv(file)

#Counts the number of individual-word matches from a particular book

df['matches_count'] = df.FAN_WORK_FILENAME.apply(lambda x: df.FAN_WORK_FILENAME.value_counts()[x])

#Creates a new dataframe with the source book, comparison book, and # of matches

newdf = df[['ORIGINAL_SCRIPT_CHARACTER','FAN_WORK_FILENAME','matches_count']]

#Adds the source/comparison/matches value to "finaldata"

finaldata = pd.concat([finaldata,newdf.drop_duplicates()], axis=0)

#Empties the dataframes used for processing the data (not "finaldata")

df = df.iloc[0:0]

newdf = newdf.iloc[0:0]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyboardInterrupt Traceback (most recent call last)

/var/folders/3r/55b5kjpd4s14_tg80r24vs7r0000gq/T/ipykernel_21699/1963970400.py in <module>

6 df = pd.read_csv(file)

7 #Counts the number of individual-word matches from a particular book

----> 8 df['matches_count'] = df.FAN_WORK_FILENAME.apply(lambda x: df.FAN_WORK_FILENAME.value_counts()[x])

9 #Creates a new dataframe with the source book, comparison book, and # of matches

10 newdf = df[['ORIGINAL_SCRIPT_CHARACTER','FAN_WORK_FILENAME','matches_count']]

~/anaconda3/envs/dsc/lib/python3.7/site-packages/pandas/core/series.py in apply(self, func, convert_dtype, args, **kwargs)

4355 dtype: float64

4356 """

-> 4357 return SeriesApply(self, func, convert_dtype, args, kwargs).apply()

4358

4359 def _reduce(

~/anaconda3/envs/dsc/lib/python3.7/site-packages/pandas/core/apply.py in apply(self)

1041 return self.apply_str()

1042

-> 1043 return self.apply_standard()

1044

1045 def agg(self):

~/anaconda3/envs/dsc/lib/python3.7/site-packages/pandas/core/apply.py in apply_standard(self)

1099 values,

1100 f, # type: ignore[arg-type]

-> 1101 convert=self.convert_dtype,

1102 )

1103

~/anaconda3/envs/dsc/lib/python3.7/site-packages/pandas/_libs/lib.pyx in pandas._libs.lib.map_infer()

/var/folders/3r/55b5kjpd4s14_tg80r24vs7r0000gq/T/ipykernel_21699/1963970400.py in <lambda>(x)

6 df = pd.read_csv(file)

7 #Counts the number of individual-word matches from a particular book

----> 8 df['matches_count'] = df.FAN_WORK_FILENAME.apply(lambda x: df.FAN_WORK_FILENAME.value_counts()[x])

9 #Creates a new dataframe with the source book, comparison book, and # of matches

10 newdf = df[['ORIGINAL_SCRIPT_CHARACTER','FAN_WORK_FILENAME','matches_count']]

~/anaconda3/envs/dsc/lib/python3.7/site-packages/pandas/core/base.py in value_counts(self, normalize, sort, ascending, bins, dropna)

964 normalize=normalize,

965 bins=bins,

--> 966 dropna=dropna,

967 )

968

~/anaconda3/envs/dsc/lib/python3.7/site-packages/pandas/core/algorithms.py in value_counts(values, sort, ascending, normalize, bins, dropna)

860

861 else:

--> 862 keys, counts = value_counts_arraylike(values, dropna)

863

864 result = Series(counts, index=keys, name=name)

~/anaconda3/envs/dsc/lib/python3.7/site-packages/pandas/core/algorithms.py in value_counts_arraylike(values, dropna)

891

892 # TODO: handle uint8

--> 893 keys, counts = htable.value_count(values, dropna)

894

895 if needs_i8_conversion(original.dtype):

KeyboardInterrupt:

To see (a sample of) what we’ve got, we can print the “finaldata” dataframe.

finaldata

To create the CSV file that we can import into a network visualization and analysis software, we need to export the dataframe as CSV.

finaldata.to_csv('6gram_finaldata.csv')

Visualizing the network#

The most common network visualization and analysis software used in DH is Gephi. Gephi and I have never gotten along. It used to vomit at my non-Latin alphabet data (that’s gotten better recently and now it even supports right-to-left scripts like Arabic or Hebrew), I find it finicky and buggy, and I don’t like its default styles. If you like Gephi, I’m not going to start a fight over it, but it’s not a tool I use.

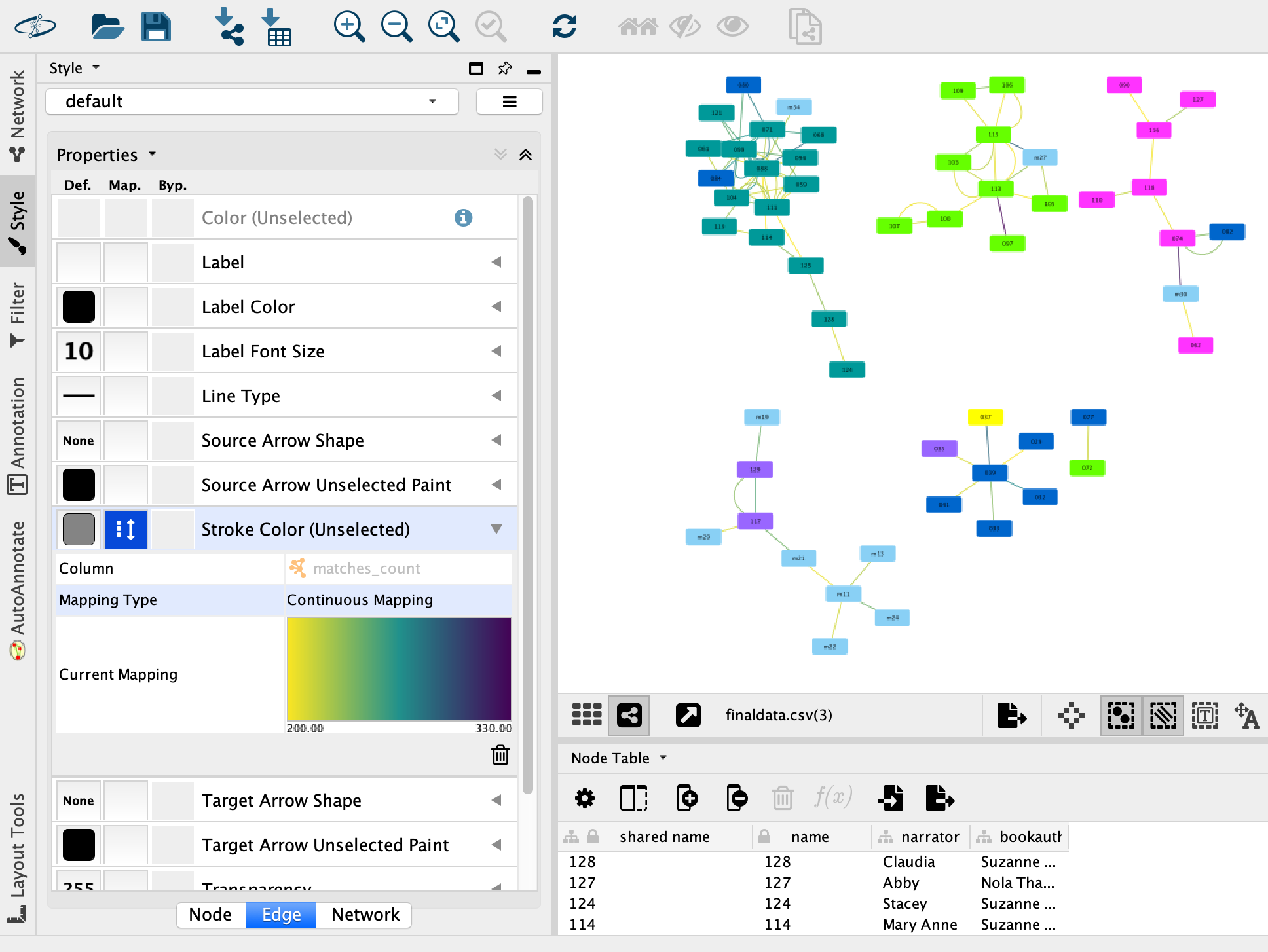

Instead, Miriam Posner’s Cytoscape tutorials (Create a network graph with Cytoscape and Cytoscape: working with attributes) were enough to get me started with Cytoscape, another cross-platform, open-source network visualization software package. The update to 3.8 changed around the interface a bit (notably, analyzing the network is no longer buried like three layers deep in the menu, under Network Analyzer → Network Analysis → Analyze Network – which I’d always joke about when teaching Cytoscape workshops), but it’s still a great and very readable tutorial, and I won’t duplicate it here.

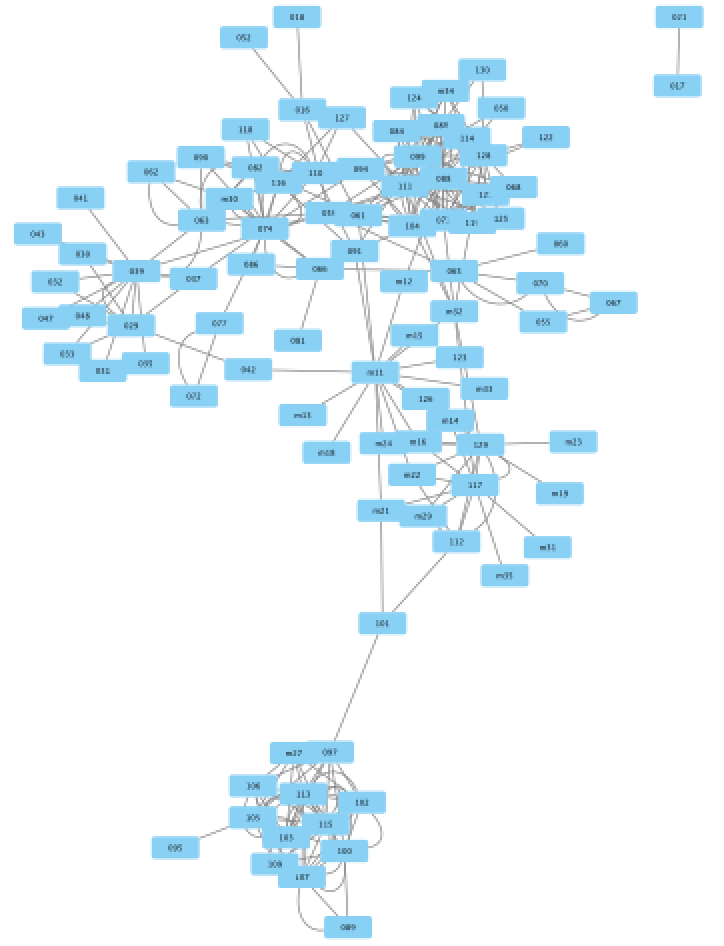

Import the 6gram_finaldata.csv file as a network and… hello blue blob!

Or, as Your Digital Humanities Peloton Instructor would put it:

Still, there’s just too much stuff there in this particular possibilities ball. Everything is connected to everything else – at least a little bit. We need to prune this tangle down to the connections that are big enough to maybe mean something.

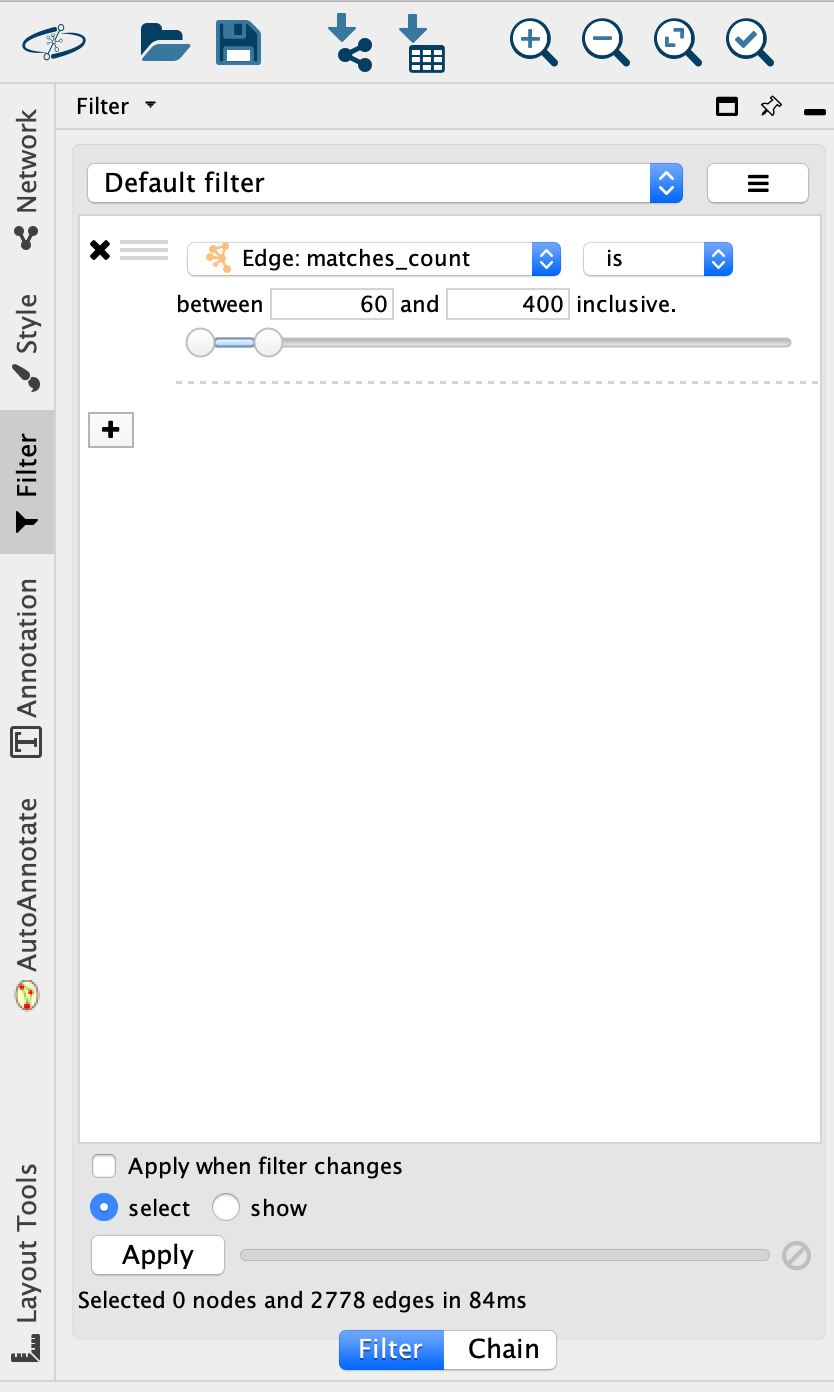

There’s a Filter vertical tab on the left side of the Cytoscape interface; let’s add a Column filter. Choose “Edges: matches_count” and set the range to be between 60 (remember, this counts tokens, so 60 = 10 matches) and 400. The max value is 4,845, but these super-high numbers aren’t actually interesting because they represent a chapter matched to itself. Then click “apply”.

If you’re working with a network as big as this one, it will look like nothing happened– this possibilities ball is so dense you can’t tell. But at the bottom of the filter window, it should say that it’s selected some large number of edges:

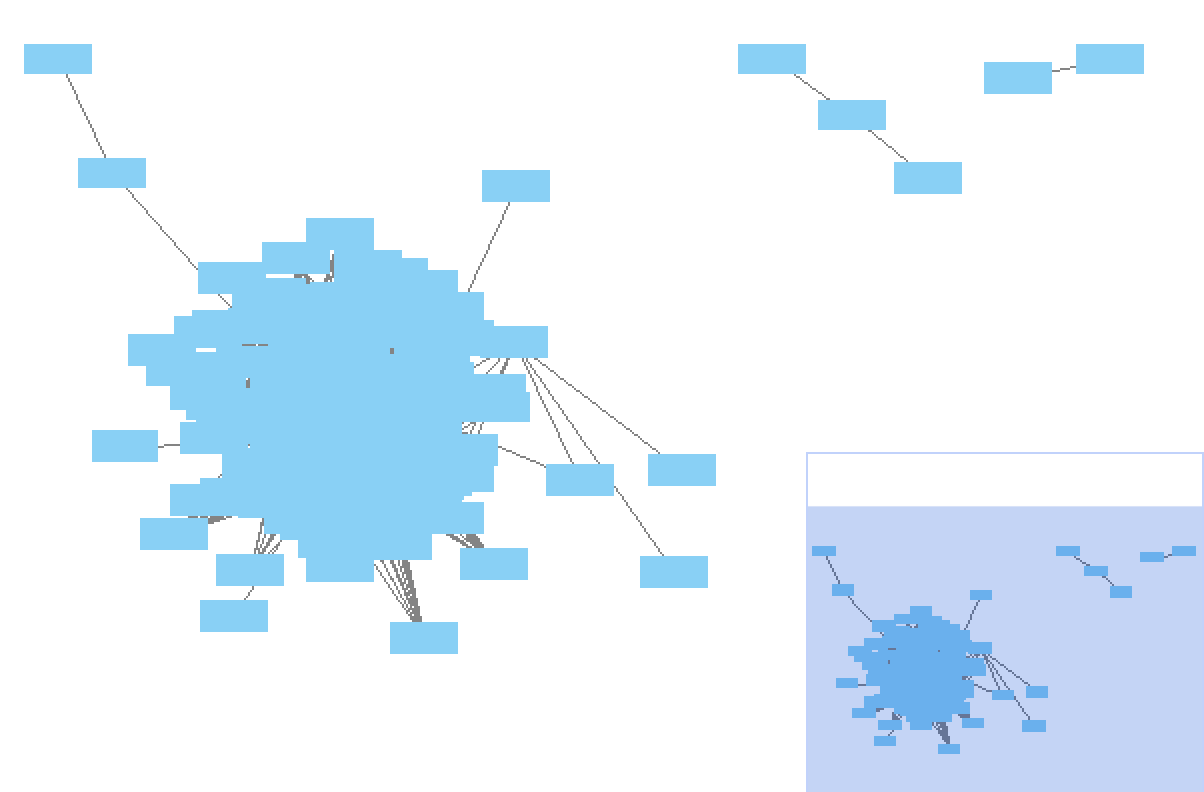

Now we want to move the things we’ve selected to a new network that’s less crowded.

Choose the “New network from Selection” button in the top toolbar:

And choose “selected nodes, selected edges”.

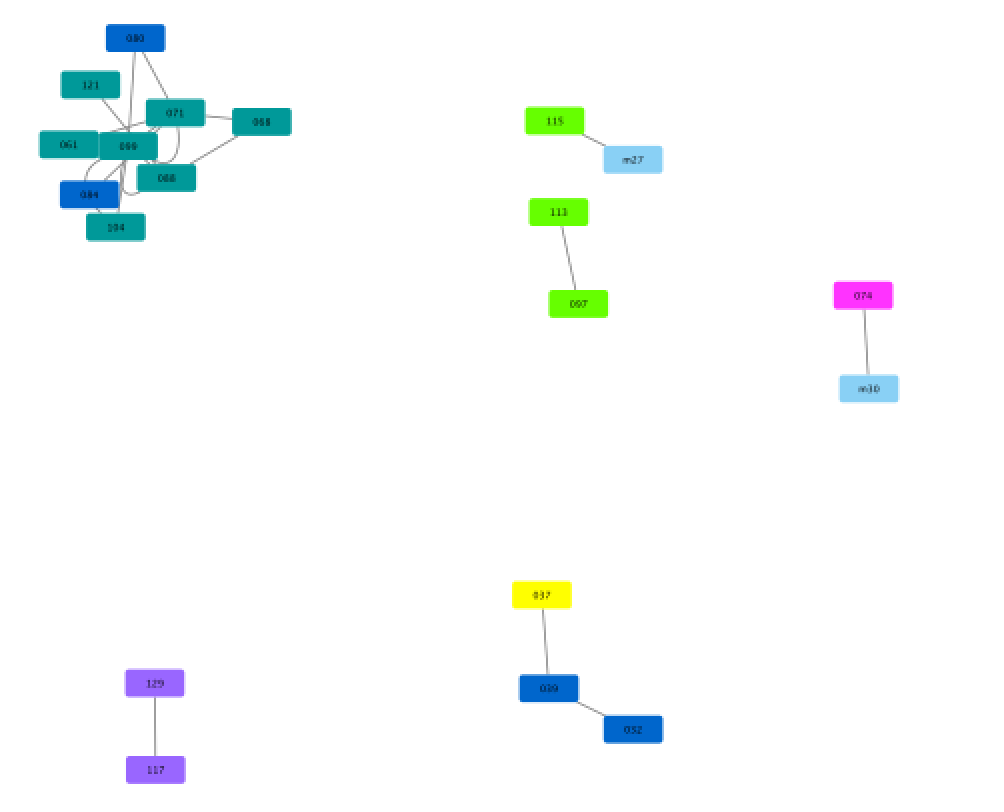

If you go to Layout → Apply preferred layout for the new network, you can start to see it as something more than a blob.

Zooming in to the isolated cluster, we see that chapter 2 of book 000 (BSC #0: The Summer Before, which was written last by Ann M. Martin as a prequel) is linked to 004 (BSC #4: Mary Anne Saves the Day) and 064 (BSC #64: Dawn’s Family Feud), which aren’t linked to anything else. Chapter 2s of BSC #15: Little Miss Stoneybrook… and Dawn and BSC #28: Welcome Back, Stacey! form a dyad.

Chapter 2 of BSC #7: Claudia and Mean Janine, is linked to many other chapter 2s, but is the only connection of BSC #8: Boy-Crazy Stacey and Mystery #28: Abby and the Mystery Baby, and one of two connections for BSC #6: Kristy’s Big Day. What’s up with books 6, 7, and 8 (written in sequence in 1987) being so closely linked to mystery 28, written in 1997? Personally, I find it easy to get pulled too far into the world of network analysis once I’ve imported my data, losing sight of what it means for some nodes to be connected and others not. To meaningfully interpret your network, though, you can’t forget about this. What does it mean that chapter 2 of BSC #7: Claudia and Mean Janine is connected to many other chapter 2s? It means that the same text repetitions (at least some of which are probably tropes) appear in all those books. With Boy-Crazy Stacey and Abby and the Mystery Baby, respectively, it shares tropes that are different tropes than those shared with other books – otherwise Boy-Crazy Stacey and Abby and the Mystery Baby would be connected to those other books, too. This is a moment where it’s really helpful to recall previous decisions you made in the workflow. Remember how we didn’t set a cut-off value in Scott’s text comparison output, in order to not lose tropes, with the consequence of some colloquial English phrases being included? If you wanted to make any sort of claim about the significance of Claudia and Mean Janine being the only connection for Boy-Crazy Stacey, this is the moment where you’d need to open up the spreadsheets for those books and look at what those matches are. Maybe BSC #6, #8, and Mystery #28 are ones where chapter 3 has all the intro prose, but they happened to have 10 “colloquial English” matches with BSC #7. That’s not where I want to take this right now, though – but don’t worry, I’m sure the Data-Sitters will get to network analysis and its perils and promises one of these days.

(By the way, if you’re getting the impression from this book that DH research is kind of like one of those Choose Your Own Adventure books with lots of branching paths and things you can decide to pursue or not – and sometimes you end up falling off a cliff or getting eaten by a dinosaur and you have to backtrack and make a different choice… you would not be wrong.)

Instead, I want to prune this down to clusters of very high repetition. Let’s adjust our filter so the minimum is 150 (meaning 25 unique 6-gram matches), create a new network with those, and apply the preferred layout.

Instead, I want to prune this down to clusters of very high repetition. Let’s adjust our filter so the minimum is 150 (meaning 25 unique 6-gram matches), create a new network with those, and apply the preferred layout.

This is getting a little more legible! But everything is still linked together in the same network except for BSC #17: Mary Anne’s Bad Luck Mystery and BSC #21: Mallory and the Trouble with Twins off in the corner.

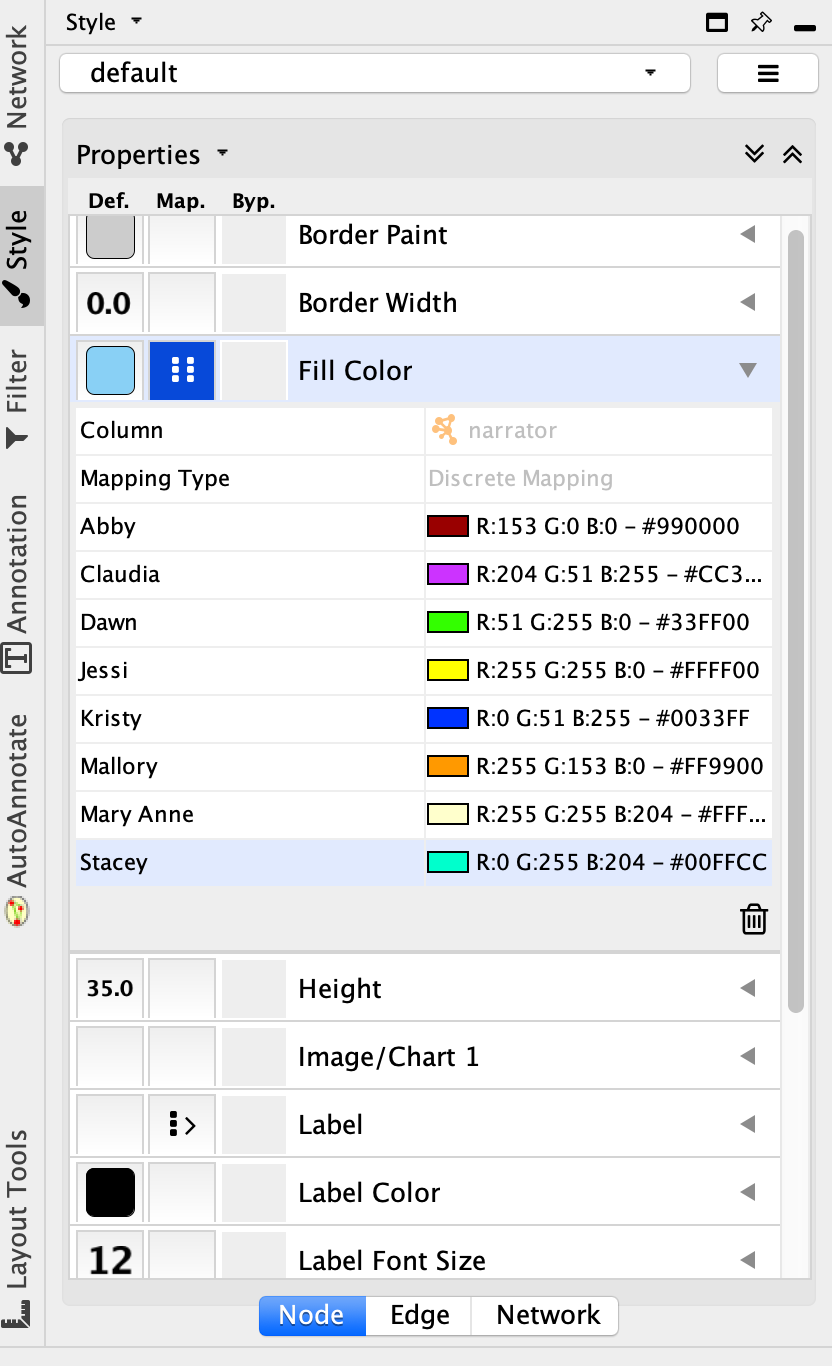

Let’s add in some attributes to see if that helps us understand what’s going on here. There are two theories we can check out easily with attributes: one is that the narrator might matter (“Does a particular character talk about herself and her friends in particular ways that lead to more repetitions?”), and the other is that the author might matter (“Is a particular author/ghostwriter more likely to reuse phrases they’ve used before?”)

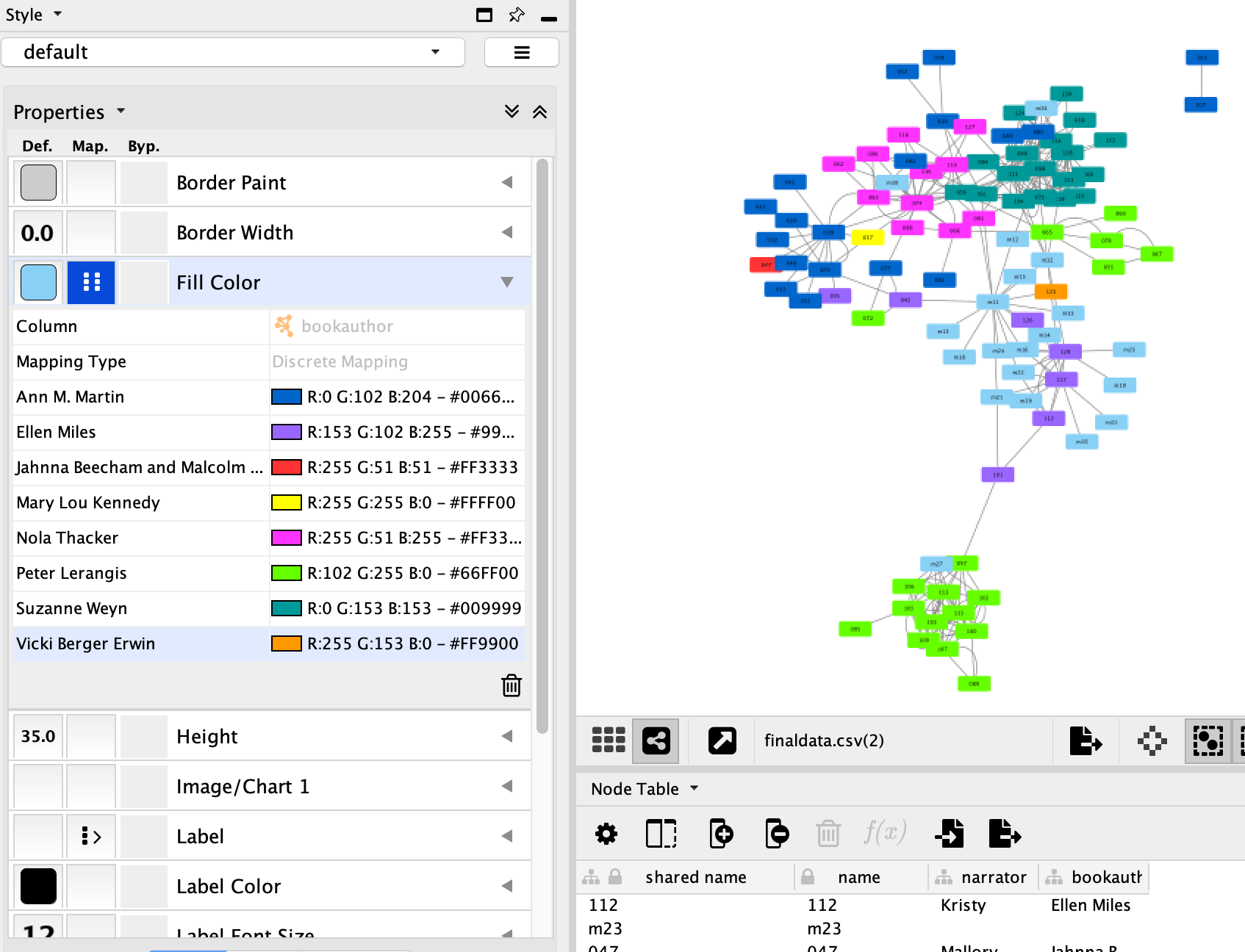

The DSC Metadata Spreadsheet has columns for the character who narrates each book, “narrator”, for the ghostwriter, “bookauthor”, along with a column with just the book number, “booknumber” that we can use to link this additional data to our original network sheet. In OpenRefine (see Lee and Quinn Clean Up Ghost Cat Hairballs for more about OpenRefine), I opened the metadata spreadsheet, went to Export → Custom tabular exporter, selected only those three column, specified it should be saved as a CSV, and hit the “Download” button.

Back in Cytoscape, I hit the “Import table from file” button in the top toolbar:

And selected the CSV file I’d just exported from OpenRefine. I set the “booknumber” column to be the key for linking the new data with the existing nodes.

Now that we have this additional information, we can go to the Style tab, choose “Node” at the bottom of that window, and toggle open “Fill color”. For the “Column” value, choose “Narrator”, and for “mapping type” choose “Discrete mapping”. Now for the fun part: assigning colors to baby-sitters! (Alas, the Baby-Sitters Club fandom wiki doesn’t list the characters’ favorite colors.)

The default blue gets applied to nodes that don’t have a value in the “narrator” column (e.g. super-specials).

And here’s what we get:

Colored by narrator, this network diagram looks kind of like a fruit salad – a well-mixed fruit salad, not one where you dump a bunch of grapes in at the end or something. It doesn’t look like we’re going to get much insight here.

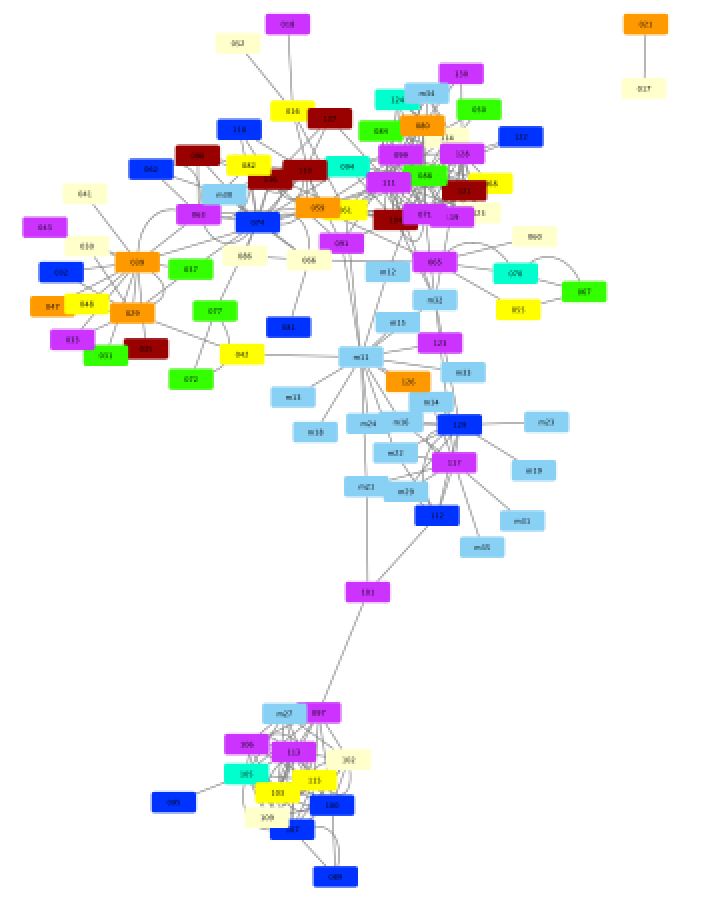

But what if we replace “narrator” with “bookauthor” and re-assign all the colors?

Now we’re on to something! There’s definitely some clustering by ghostwriter here.

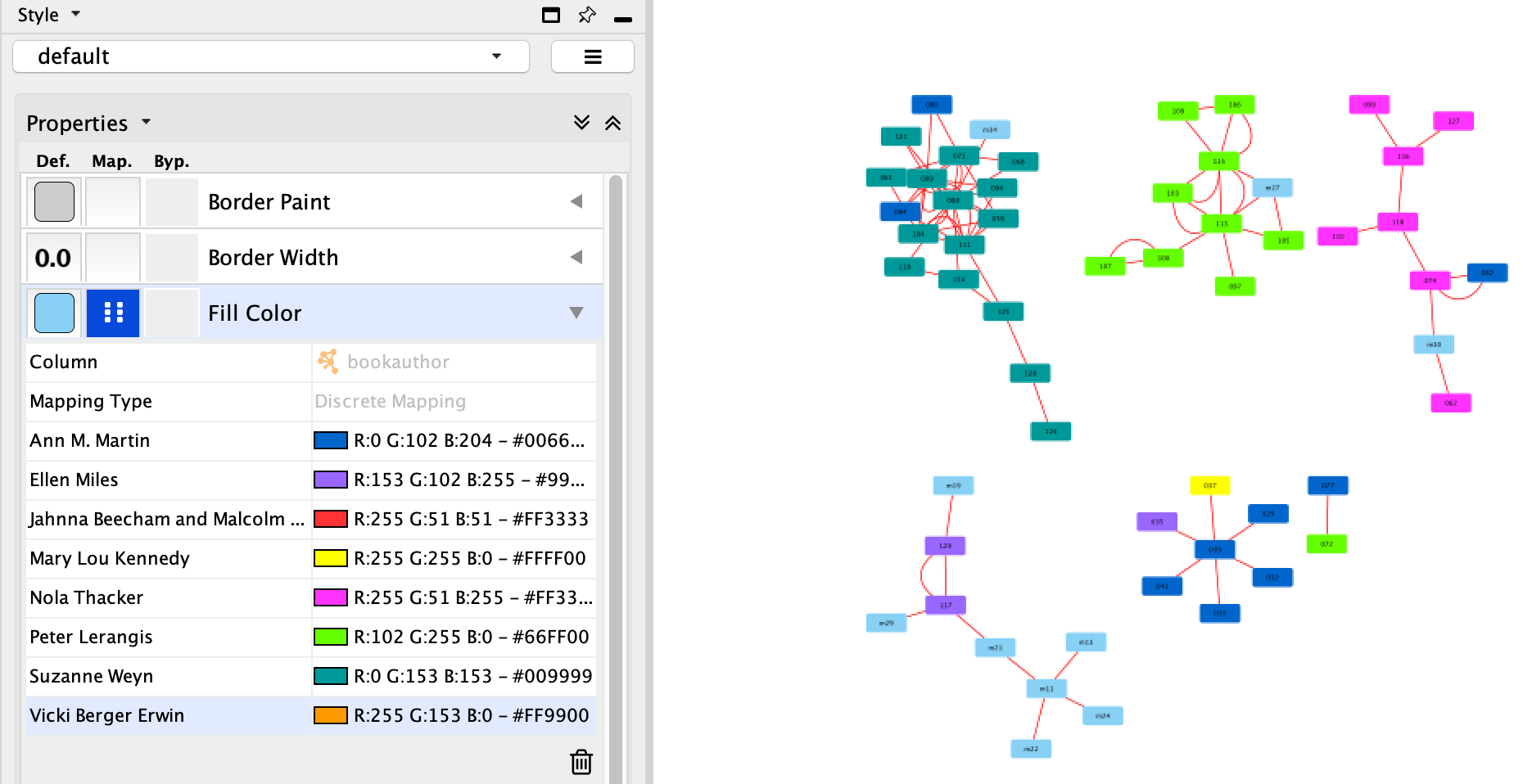

What if we turn up the threshold to 200 repeated tokens?

Some of the authors disappear altogether, and the clusters break off:

What if we keep going? Turning the threshold up to 250 gets us this:

And once you hit 300, you’re left with:

It looks like 200 was our sweet spot. Let’s do one more thing to enhance that network to surface some of the even more intense overlaps.

Back in the “Style” panel for the network of books that share 200 or more matched tokens, toggle open “Stroke color” and choose “matches_count” as the column. This time, choose “continuous” for the mapping type. It will automatically show a gradient where bright yellow indicates 200 matched tokens, and dark purple indicates 330 (the maximum). Now we can see most of the connections skew towards the lower end of this range (though Suzanne Weyn, in turquoise, leans more heavy on text reuse).

So I started wondering if I had stumbled over the beginning to a new Multilingual Mystery: what does this look like in French? If you look at chapter 2 in translation, are they less repetitive? If I ran the same code on the translations that co-exist in a text-repetition cluster, would there be a similar amount of repetition? Or might the translator be a mitigating factor – where there might be a sub-cluster of the translator directly copying text they’d previously translated from another novel in the cluster?

A different direction#

I was so very delighted with my little color-coded network visualization and my plans to extend it to the French that I was caught off-guard when I met with Mark and he seemed less than sanguine about it all. He pointed out (and I should’ve thought of this) that French inflection would probably add some further noise to the results of Scott’s comparison tool, and I should probably lemmatize the text too (change all the words to their dictionary form to get around word-count related problems caused by inflection). And even with the English, he seemed a bit quizzical that this sort of n-gram comparison was where I started with text comparison. He suggested that I might check out other distance metrics, like cosine distance or TF-IDF, if I hadn’t yet.

“One of the things that I find a bit frustrating about off-the-shelf methods is that a lot of DH people hear words that are similar and so think that they can mean the same thing. Just because there’s a statistical method called ‘innovation’ (which measures how much word usage changes over the course of a document from beginning to end), that doesn’t mean that it’s a statistical method that can measure literary innovation. To bridge that gap, you have to either adapt the method or adapt your definition of literary innovation,” cautioned Mark. “Now, your logic goes: people talk about chapter two being similar across books, similarity can imply a kind of repetition, repetition can manifest in a re-use of specific language between texts, Scott’s method measures re-use of language, therefore you’re thinking you can use Scott’s method to measure similarity. But there is a LOT of translation going on there: similarity → repetition → re-use → common 6-grams. Were someone to do this unthinkingly, they could very easily miss this chain of reasoning and think that common 6-grams is measuring textual similarity.”

(Dear readers, please don’t make that mistake! We’ve got, admittedly, a very specific situation that justifies using it with the Baby-Sitters Club corpus, but please make sure you’ve got a similarly well-justified situation before trying it.)

“In your case,” Mark added, “I think this might be right in terms of how you are thinking about similarity, but in general, this seems like a constant problem in DH. When people hear ‘are similar to’ they don’t necessarily jump immediately (or ever) to, uses the same phrases – this is why first thinking through what you mean by ‘similar’ and THEN moving to choosing a method that can try to represent that is a crucial step.” He paused for a moment. “Not everyone would agree, though. Ted Underwood thinks we should just model everything and sort out what means what later.”

I laughed. This is how DH gets to be so fun and so maddening all at once. Not only can’t we all agree on what the definition of DH is, we also don’t even always see eye-to-eye about what the crucial first step is.

I’d never run the more common text similarity metrics that Mark had mentioned, but I knew just where to start. The Programming Historian had just published a new lesson by John R. Ladd on common similarity measures that covered distance metrics, and I’d been a reviewer on Matthew J. Lavin’s lesson on TF-IDF before starting the Data-Sitters Club. Both those lessons are worth reading through if you’re interested in trying out these techniques yourself, but I’ll cover them here, Data-Sitters Club style.

What do we compare when we compare texts?#

But before getting into the difference distance metrics, let’s talk about what we actually measure when we measure “text similarity” computationally. If you ask someone how similar two books, or two series are, the metrics they use are probably going to depend on the pair you present them with. How similar are BSC #10: Logan Likes Mary Anne and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre? Well, they both involve the first-person narration of a teenage female protagonist, a romance subplot, and childcare-based employment – but probably no one would think of these books as being all that similar, due to the difference in setting and vastly different levels of cultural prestige, if nothing else. What about Logan Likes Mary Anne compared to Sweet Valley High #5: All Night Long, where teenage bad-twin Jessica starts dating a college boy, stays out all night with him, and asks good-twin Liz to take a test for her? The setting is a lot more similar (1980’s affluent suburban United States) and there’s also a romance subplot, but SVH #5 is written in the third person, the series is for a much edgier audience than the Baby-Sitters Club, and the character of Mary Anne is probably more similar to Jane Eyre than Jessica Wakefield.

It’s easy for a human reader to evaluate book similarity more holistically, comparing different aspects of the book and combining them for an overall conclusion that takes them all into consideration. And if you’ve never actually tried computational text similarity methods but hear DH people talking about “measuring text similarity”, you might get the idea that computers are able to measure the similarity of texts roughly the way that humans do. Let me assure you: they cannot.

No human would compare texts the way computers compare texts. That doesn’t mean the way computers do it is wrong – if anything, critics of computational literary analysis have complained about how computational findings are things people already know. Which suggests that even though computers go about it differently, the end result can be similar to human evaluation. But it’s important to keep in mind that your results are going to vary so much based on what you measure.

So what are these things computers measure? Can they look at characters? Plot? Style? Ehhh…. Computational literary scholars are working on all that. And in some cases, they’ve found ways of measuring proxies for those things, that seem to basically work out. But those things are too abstract for a computer to measure directly. What a computer can measure is words. There’s tons of different ways that computers can measure words. Sometimes we use computers to just count words, for word frequencies. Computers can look at which words tend to occur together through something like n-grams, or more complex methods for looking at word distributions, like topic modeling or word vectors. We’ll get to those in a future DSC book. With languages that have good natural-language processing tools (and English is the best-supported language in the world), you can look at words in a slightly more abstract way by annotating part-of-speech information for each word, or annotating different syntactic structures. Then you can do measurements based on those: counting all the nouns in a text, looking at which verbs are most common across different texts, counting the frequency of dependent clauses.

It turns out that looking at the distributions of the highest-frequency words in a text is a way to identify different authors. So if you’re interested more in what the text is about, you need to look at a large number of words (a few thousand), or just look at the most common nouns to avoid interference from what’s known as an “author signal”. The choice of what words you’re counting – and how many – is different than the choice of what algorithm you use to do the measuring. But it’s at least as important, if not more so.

So the process of comparing texts with these distance measures looks something like this:

Choose what you want to measure. If you’re not sure, you can start with something like the top 1,000 words, because that doesn’t require you to do any computationally-intensive pre-processing, like creating a derivative text that only includes the nouns– you can work directly with the plain-text files that make up your corpus. Whatever number you choose as the cutoff, though, needs to be sensitive to the length of the texts in your corpus. If your shortest text is 1,000 words and your longest text is 10,000 words, do you really want a cutoff that will get every single word (with room to spare once you consider duplicate words) in one of your texts? Also, you may want to be more picky than just using the top 1,000 words, depending on the corpus. With the Baby-Sitters Club corpus, character names are really important, and most characters recur throughout the series. But if you’re working with a huge corpus of 20th-century sci-fi, you might want to throw out proper names altogether, so that the fact that each book has different characters doesn’t obscure significant similarities in, for instance, what those characters are doing. Similarly, all the Baby-Sitters Club books are written in the first person, from one character’s perspective (or multiple characters’ perspective, in the case of the Super Specials). If you’re working with multiple series, or books that aren’t in a series, you could reasonably choose to throw out personal pronouns so that the difference between “I” and “she/he” doesn’t mess with your similarity calculations.

Normalize your word counts. (I didn’t know about this at first, and didn’t do it the first time I compared the texts, but it turns out to be really important. More on that adventure shortly!) While some text comparison algorithms are more sensitive to differences in text length, you can’t get around the fact that two occurrences of a word are more significant in a 100-word text than a 1,000-word text, let alone a 10,000-word text. To account for this, you can go from word counts to word frequencies, dividing the number of occurrences of a given word by the total number of words. (There’s code for this in the Jupyter notebook, you don’t have to do it by hand.)

Choose a method of comparing your texts. Euclidean distance and cosine distance have advantages and disadvantages that I get into below, and TF-IDF combined with one of those distance measures gives you a slightly different view onto your text than if you just use word counts, even normalized.

“Vectorize” your text. This is the process that, basically, “maps” each text to a set of coordinates. It’s easy to imagine this taking the form of X, Y coordinates for each text, but don’t forget what we’re actually counting: frequencies of the top 1,000 words. There’s a count-value for each one of those 1,000 words, so what’s being calculated are coordinates for each text in 1000-dimensional space. It’s kinda freaky to try to imagine, but easier if you think of it less as 1000-dimensional space, and more as a large spreadsheet with 1,000 rows (one for each word), and value for each row (the word count or frequency for each). Each of those row-values is the coordinates of the text in that one dimension. You could just pick two words, and declare them your X and Y coordinates – and maybe that might even be interesting, depending on the words you pick! (Like, here’s a chart of the frequency of Kristy to Claudia.) But in almost all cases, we want the coordinates for the text-point to incorporate data from all the words, not just two. And that’s how we end up in 1000-dimensional space. The good news is that you don’t have to imagine it: we’re not trying to visualize it yet, we’re just telling Python to create a point in 1000-dimensional space for each text.

Measure the distance between your text-points. There’s two common ways to do this: Euclidean distance and cosine distance.

Look at the results and figure out what to make of it. This is the part that the computer can’t help you with. It’s all up to you and your brain. 🤯

With that big-picture view in mind, let’s take a look at some of the distance measures.

Euclidean distance#

One of the things that I find striking about using Euclidean distance to measure the distance between text-points is that it actually involves measuring distance. Just like you did between points on your classic X, Y axis graph from high school math. (Hello, trigonometry! I have not missed you or needed you at all until now.)

The output of Scott’s tool is more intuitively accessible than running Euclidean distance on text-points in 1000-dimensional space. His tool takes in text pairs, and spits out 6-grams of (roughly) overlapping text. With Euclidean and cosine distance, what you get back is a number. You can compare that number to numbers you get back for other pairs of texts, but the best way to make sure that you’re getting sensible results is to be familiar with the texts in question, and draw upon that knowledge for your evaluation. What I’m really interested in is the “chapter 2” question, but I don’t have a good sense of the content of all the books’ chapter 2s. So instead, we’ll start exploring these analyses on full books, and once we understand what’s going on, we can apply it to the chapter 2s.

#Imports the count vectorizer from Scikit-learn along with

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

#Glob is used for finding path names

import glob

#We need these to format the data correctly

from scipy.spatial.distance import pdist, squareform

#In case you're starting to run the code just at this point, we'll need os again

import os

#In case you're starting to run the code just at this point, we'll need pandas again

import pandas as pd

Put the full path to the folder with your corpus of plain text files between the single quotes below.

filedir = '/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/dsc_corpus_clean'

os.chdir(filedir)

If you’re looking at the code itself in the Jupyter notebook for this book, you’ll see we’re using the Scikit-learn Python module’s CountVectorizer class, which counts up all the words in all the texts you give it, filtering out any according to the parameters you give it. You can do things like strip out, for instance, words that occur in at least 70% of the text by adding max_df = .7 after max_features. That’s the default suggested by John R. Ladd’s Programming Historian tutorial on text similarity metrics, and I figured I’d just run with it while exploring this method.

Want to know how long it took me to realize that was an issue with the results I was getting? I’ve been writing this book on and off for six months.

It took until… the night I was testing the Jupyter notebook version, to publish it the next day. To say that I’m not a details person is truly an understatement. But you really do have to be careful with this stuff, and seriously think through the implications of the choices you make, even on seemingly small things like this.

Because the book is written around that mistake, I’m leaving it in for the Euclidean distance and cosine sections. Don’t worry, we’ll come back to it.

Anyhow, as you see below, before you can measure the distance between texts in this trippy 1000-dimensional space, you need to transform them into a Python array because SciPy (the module that’s doing the measuring) wants an array for its input. “Because the next thing in my workflow wants it that way” is a perfectly legitimate reason to change the format of your data, especially if it doesn’t change the data itself.

# Use the glob library to create a list of file names, sorted alphabetically

# Alphabetical sorting will get us the books in numerical order

filenames = sorted(glob.glob("*.txt"))

# Parse those filenames to create a list of file keys (ID numbers)

# You'll use these later on.

filekeys = [f.split('/')[-1].split('.')[0] for f in filenames]

# Create a CountVectorizer instance with the parameters you need

vectorizer = CountVectorizer(input="filename", max_features=1000, max_df = .7)

# Run the vectorizer on your list of filenames to create your wordcounts

# Use the toarray() function so that SciPy will accept the results

wordcounts = vectorizer.fit_transform(filenames).toarray()

Here’s an important thing to remember, though, before running off to calculate the Euclidean distance between texts: it is directly measuring the distance between our text-points in 1000-dimensional space. And those points in 1000-dimensional space were calculated based on word counts – meaning that for long texts, words will generally have a higher word count. Even if you’re comparing two texts that have the exact same relative frequency of all the words (imagine if you have one document with a 500-word description of a Kristy’s Krushers baseball game, and another document with that same 500-word description printed twice), running Euclidean distance after doing word-counts will show them as being quite different, because the word counts in one text are twice as big as in the other text. One implication of this is that you really need your texts to be basically the same length to get good results from Euclidean distance.

I started off trying out Euclidean distance, running with the assumption that the Baby-Sitters Club books are all pretty much the same length. All the main and mystery series have 15 chapters, so it probably all works out, right?

#Runs the Euclidean distance calculation, prints the output, and saves it as a CSV

euclidean_distances = pd.DataFrame(squareform(pdist(wordcounts)), index=filekeys, columns=filekeys)

euclidean_distances

| 000_the_summer_before | 001_kristys_great_idea | 002_claudia_and_the_phantom_phone_calls | 003_the_truth_about_stacey | 004_mary_anne_saves_the_day | 005_dawn_and_the_impossible_three | 006_kristys_big_day | 007_claudia_and_mean_jeanine | 008_boy_crazy_stacey | 009_the_ghost_at_dawns_house | ... | ss06_new_york_new_york | ss07_snowbound | ss08_baby_sitters_at_shadow_lake | ss09_starring_the_baby_sitters_club | ss10_sea_city_here_we_come | ss11_baby_sitters_remember | ss12_here_come_the_bridesmaids | ss13_aloha_baby_sitters | ss14_bs_in_the_usa | ss15_baby_sitters_european_vacation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000_the_summer_before | 0.000000 | 184.496612 | 177.146832 | 208.760628 | 179.924984 | 350.028570 | 224.748749 | 309.441432 | 227.694971 | 235.291309 | ... | 199.984999 | 260.173019 | 312.240292 | 357.544403 | 225.039996 | 195.017948 | 244.325602 | 202.573443 | 190.000000 | 209.857094 |

| 001_kristys_great_idea | 184.496612 | 0.000000 | 137.032843 | 208.652822 | 186.413519 | 338.223299 | 204.531171 | 338.657644 | 223.481543 | 213.248681 | ... | 226.717886 | 245.908520 | 301.209230 | 348.133595 | 220.099977 | 199.080386 | 226.900859 | 190.060517 | 168.395368 | 190.905736 |

| 002_claudia_and_the_phantom_phone_calls | 177.146832 | 137.032843 | 0.000000 | 174.401835 | 177.273800 | 344.251362 | 209.911886 | 291.054978 | 232.413425 | 223.461406 | ... | 233.274516 | 251.254851 | 308.014610 | 345.816425 | 224.437074 | 200.576669 | 233.229501 | 192.257640 | 176.722947 | 192.834126 |

| 003_the_truth_about_stacey | 208.760628 | 208.652822 | 174.401835 | 0.000000 | 227.894713 | 378.485138 | 254.956859 | 334.109264 | 277.690475 | 261.065126 | ... | 246.667793 | 293.061427 | 344.567845 | 380.642877 | 265.160329 | 237.181365 | 274.896344 | 247.667115 | 232.122812 | 246.594809 |

| 004_mary_anne_saves_the_day | 179.924984 | 186.413519 | 177.273800 | 227.894713 | 0.000000 | 346.119921 | 224.911094 | 282.044323 | 230.082594 | 238.228882 | ... | 248.066523 | 258.404721 | 316.175584 | 356.318678 | 222.652195 | 216.460158 | 246.937239 | 185.302455 | 194.157153 | 211.359883 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| ss11_baby_sitters_remember | 195.017948 | 199.080386 | 200.576669 | 237.181365 | 216.460158 | 355.389927 | 226.168079 | 352.374800 | 244.215069 | 254.432702 | ... | 213.696046 | 258.290534 | 317.723150 | 347.450716 | 243.287895 | 0.000000 | 233.077240 | 205.572372 | 188.329498 | 199.854947 |

| ss12_here_come_the_bridesmaids | 244.325602 | 226.900859 | 233.229501 | 274.896344 | 246.937239 | 292.982935 | 227.971489 | 384.029947 | 263.727132 | 272.633454 | ... | 269.241527 | 274.366543 | 336.937680 | 371.934134 | 223.919628 | 233.077240 | 0.000000 | 227.681795 | 208.861198 | 226.982378 |

| ss13_aloha_baby_sitters | 202.573443 | 190.060517 | 192.257640 | 247.667115 | 185.302455 | 347.180069 | 220.063627 | 353.120376 | 213.201782 | 244.842807 | ... | 229.691097 | 248.704644 | 303.446865 | 345.976878 | 207.352357 | 205.572372 | 227.681795 | 0.000000 | 136.213068 | 132.785541 |

| ss14_bs_in_the_usa | 190.000000 | 168.395368 | 176.722947 | 232.122812 | 194.157153 | 335.168614 | 202.499383 | 357.018207 | 216.640255 | 227.973683 | ... | 206.760731 | 235.826207 | 294.197213 | 339.973528 | 208.885136 | 188.329498 | 208.861198 | 136.213068 | 0.000000 | 145.113748 |

| ss15_baby_sitters_european_vacation | 209.857094 | 190.905736 | 192.834126 | 246.594809 | 211.359883 | 343.991279 | 219.335360 | 367.132129 | 233.535864 | 245.959346 | ... | 227.046251 | 252.994071 | 309.376793 | 329.019756 | 226.285218 | 199.854947 | 226.982378 | 132.785541 | 145.113748 | 0.000000 |

224 rows × 224 columns

euclidean_distances.to_csv('euclidean_distances_count.csv')

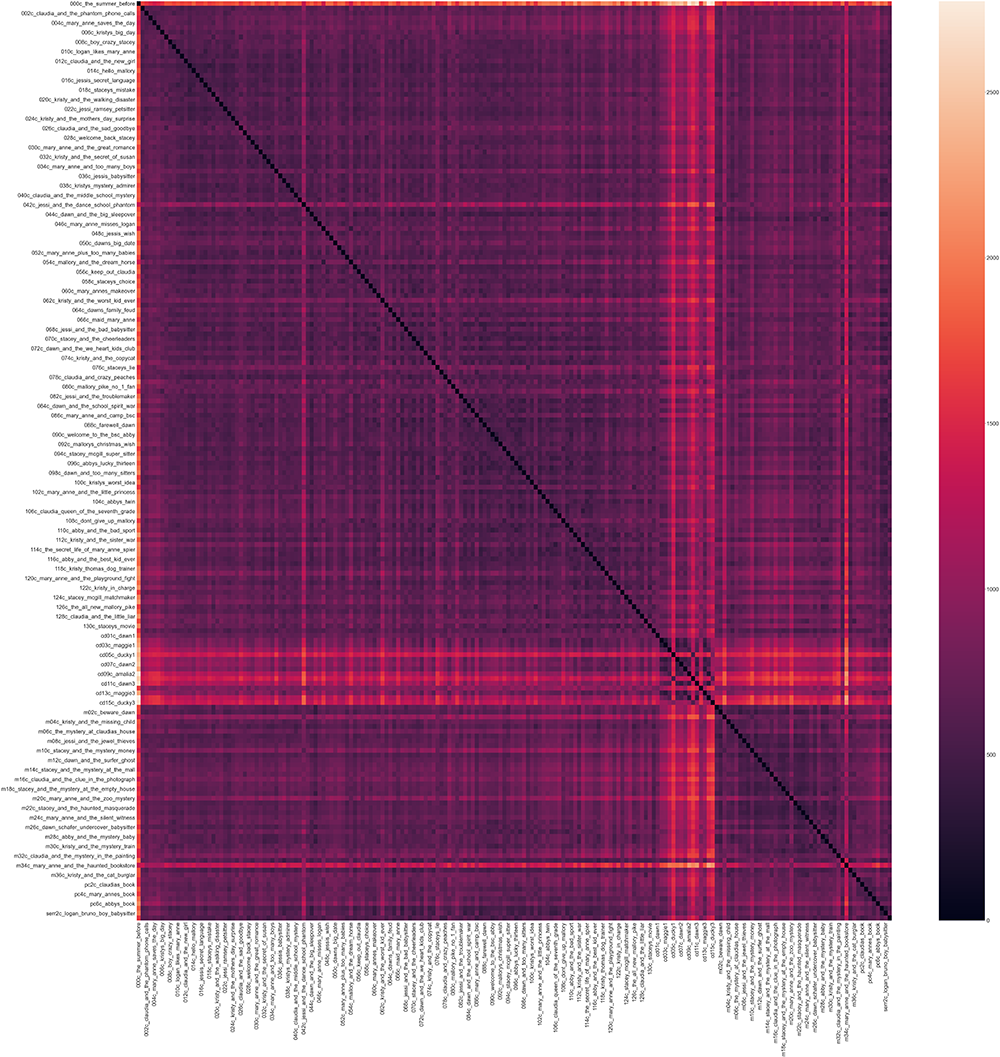

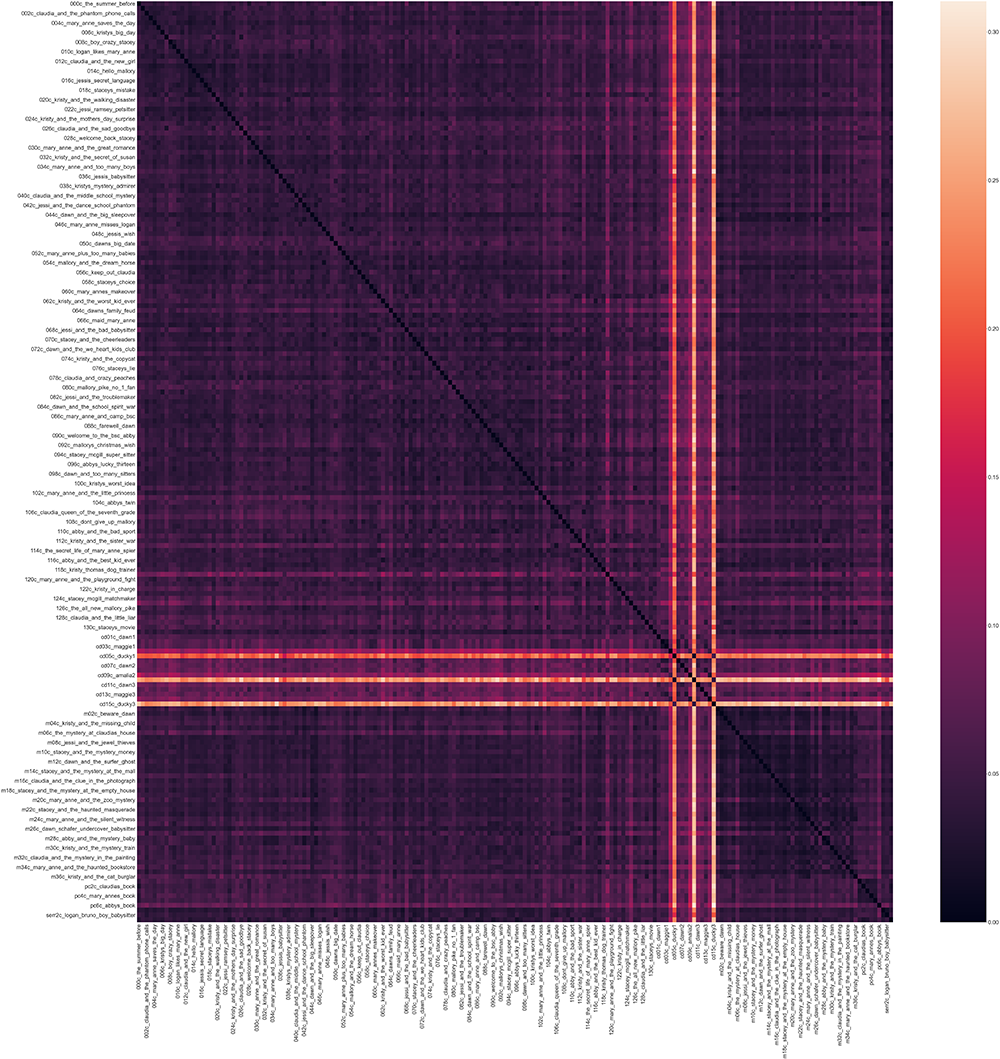

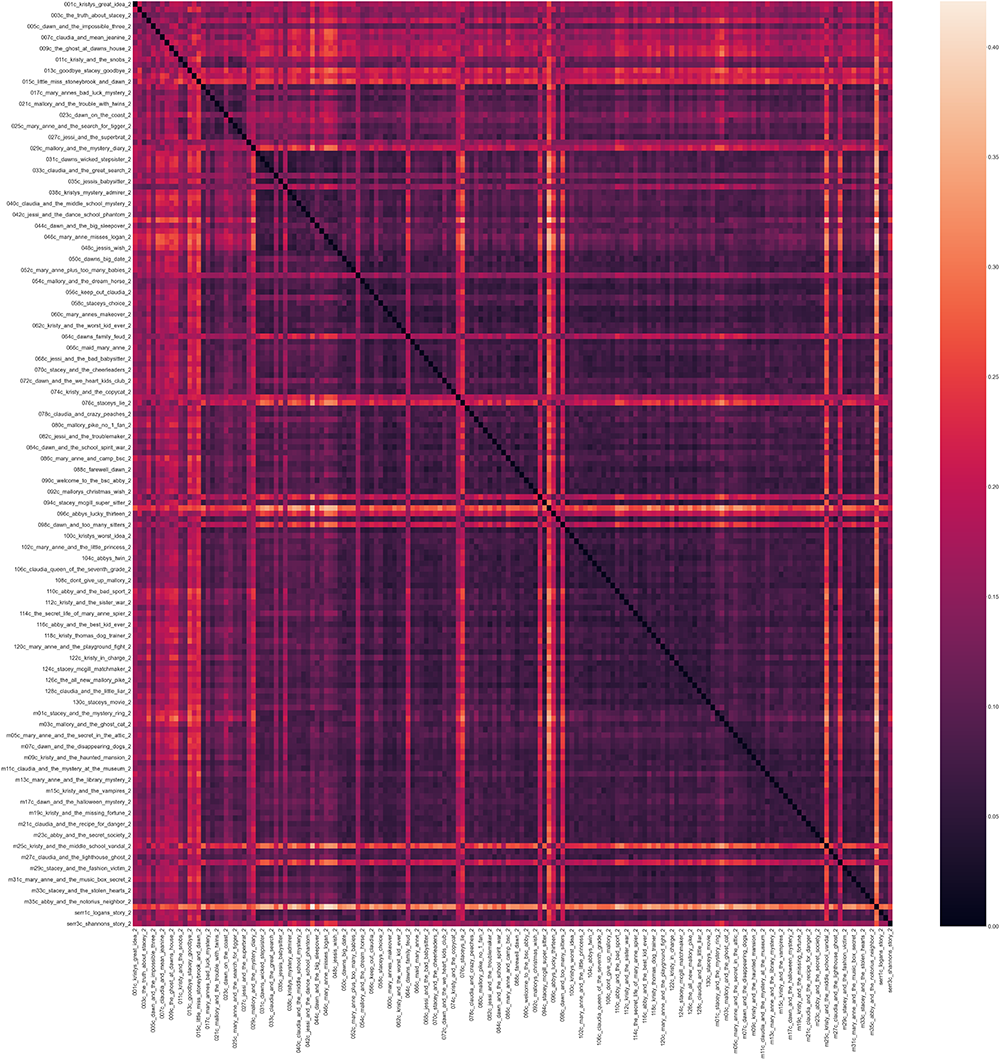

No one really likes looking at a giant table of numbers, especially not for a first look at a large data set. So let’s visualize it as a heatmap. We’ll put all the filenames along the X and Y axis; darker colors represent more similar texts. (That’s why there’s a black line running diagonally – each text is identical to itself.)

The code below installs the seaborn visualization package (which doesn’t come with Anaconda by default, but if it’s already installed, you can skip that cell), imports matplotlib (our base visualization library), and then imports seaborn (which provides the specific heatmap visualization).

#Installs seaborn

#You only need to run this cell the first time you run this notebook

import sys

!{sys.executable} -m pip install seaborn

#Import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#Import seaborn

import seaborn as sns

#Defines the size of the image

plt.figure(figsize=(100, 100))

#Increases the label size so it's more legible

sns.set(font_scale=3)

#Generates the visualization using the data in the dataframe

ax = sns.heatmap(euclidean_distances)

#Displays the image

plt.show()

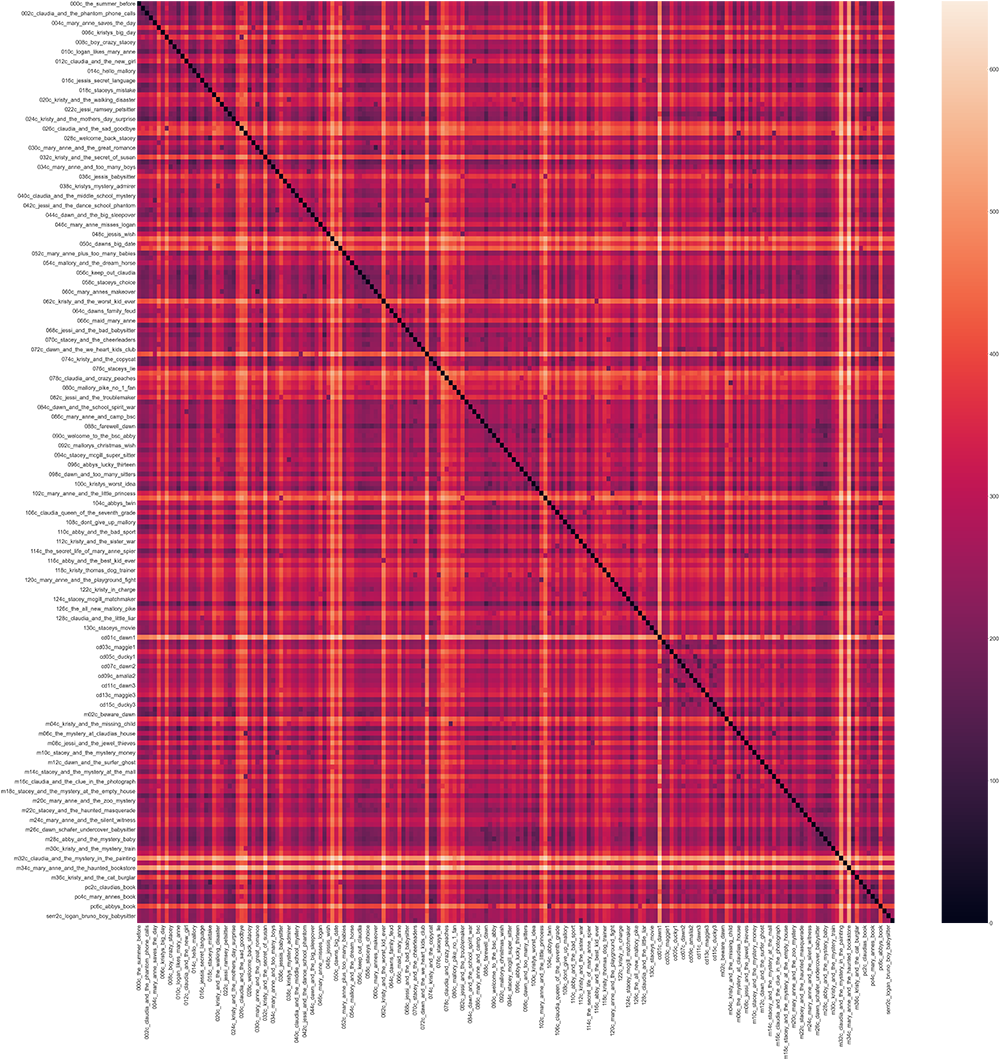

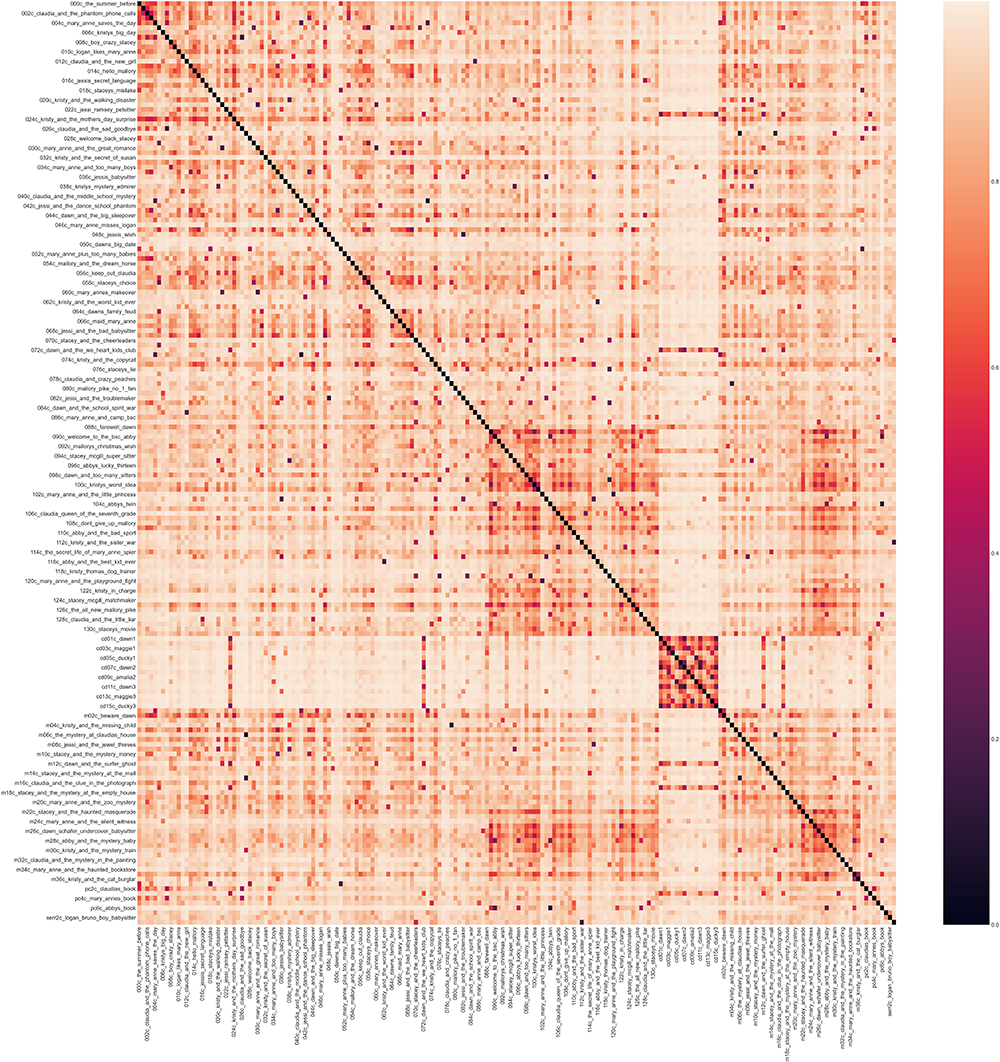

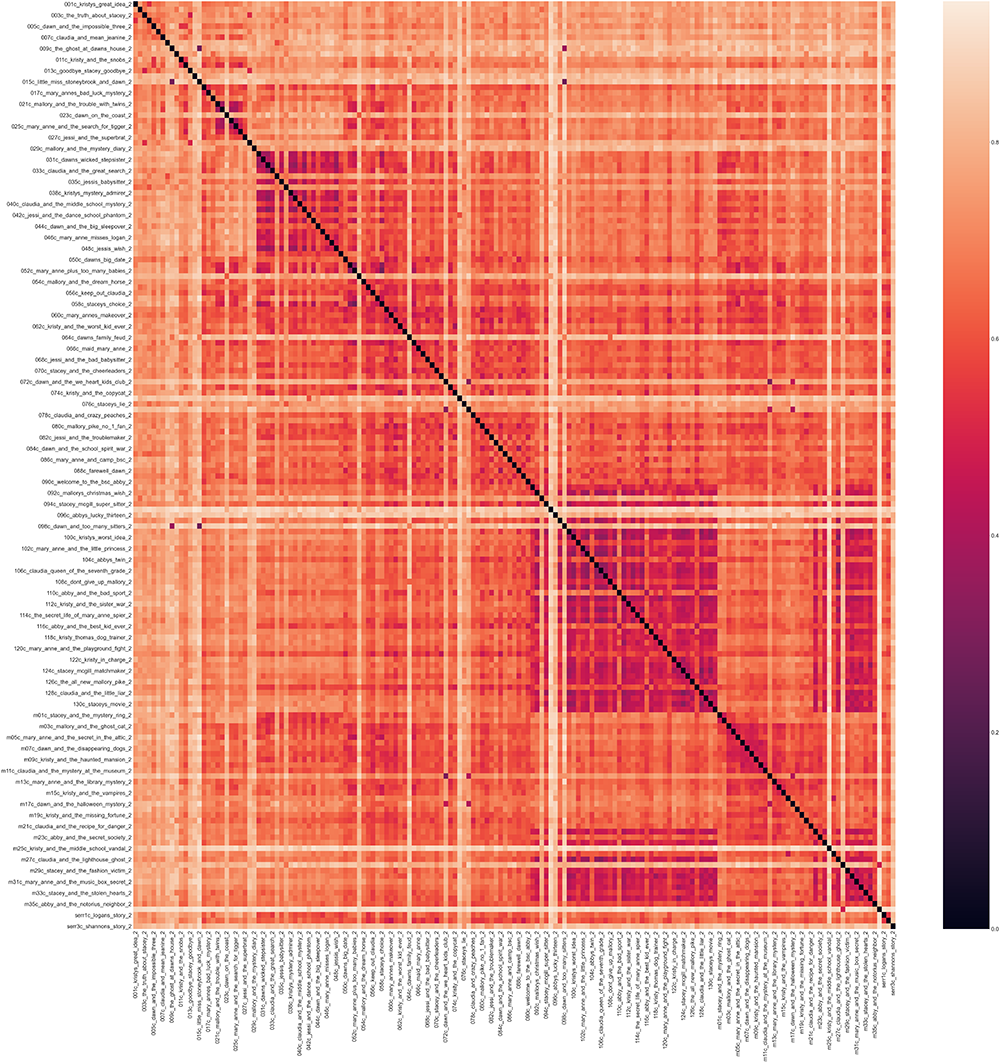

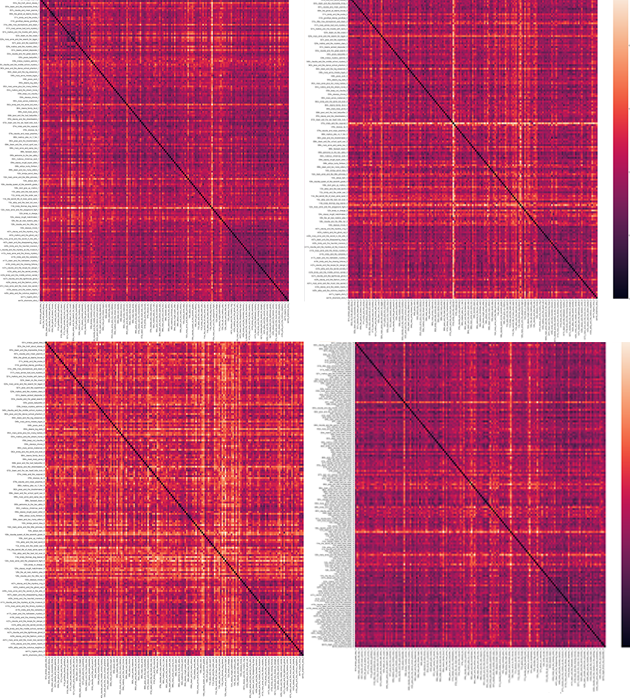

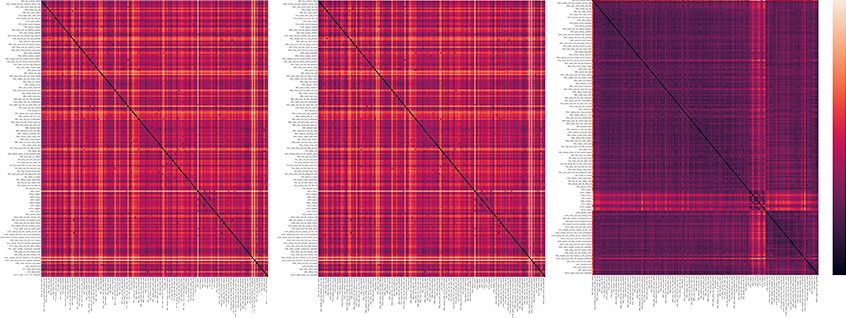

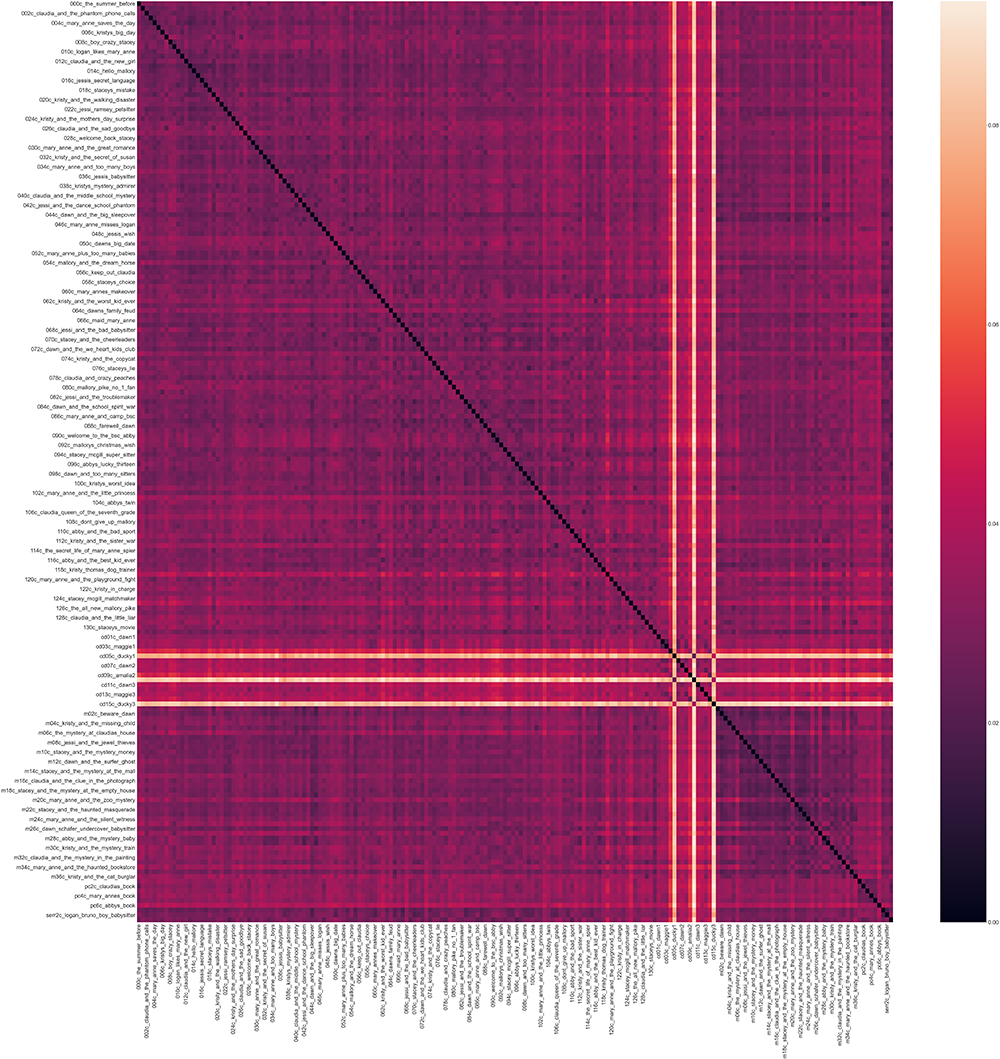

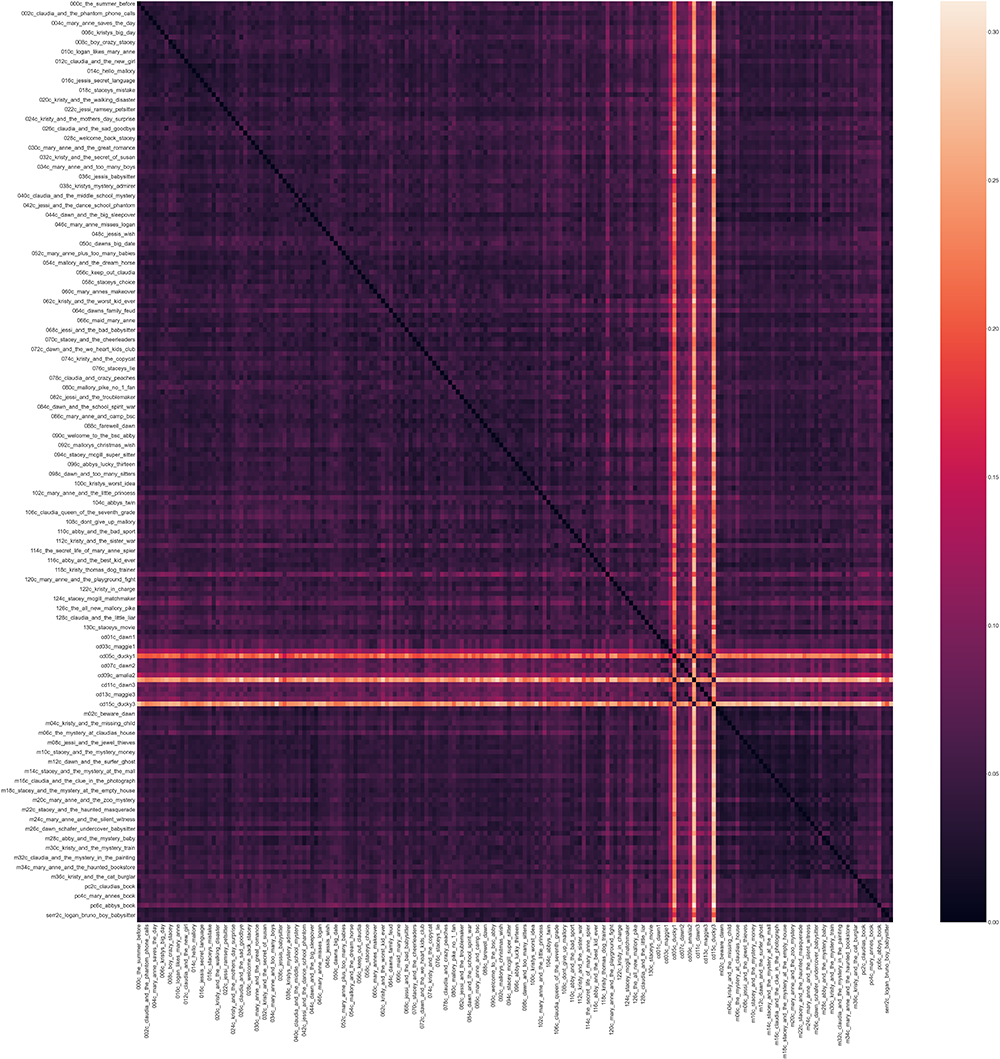

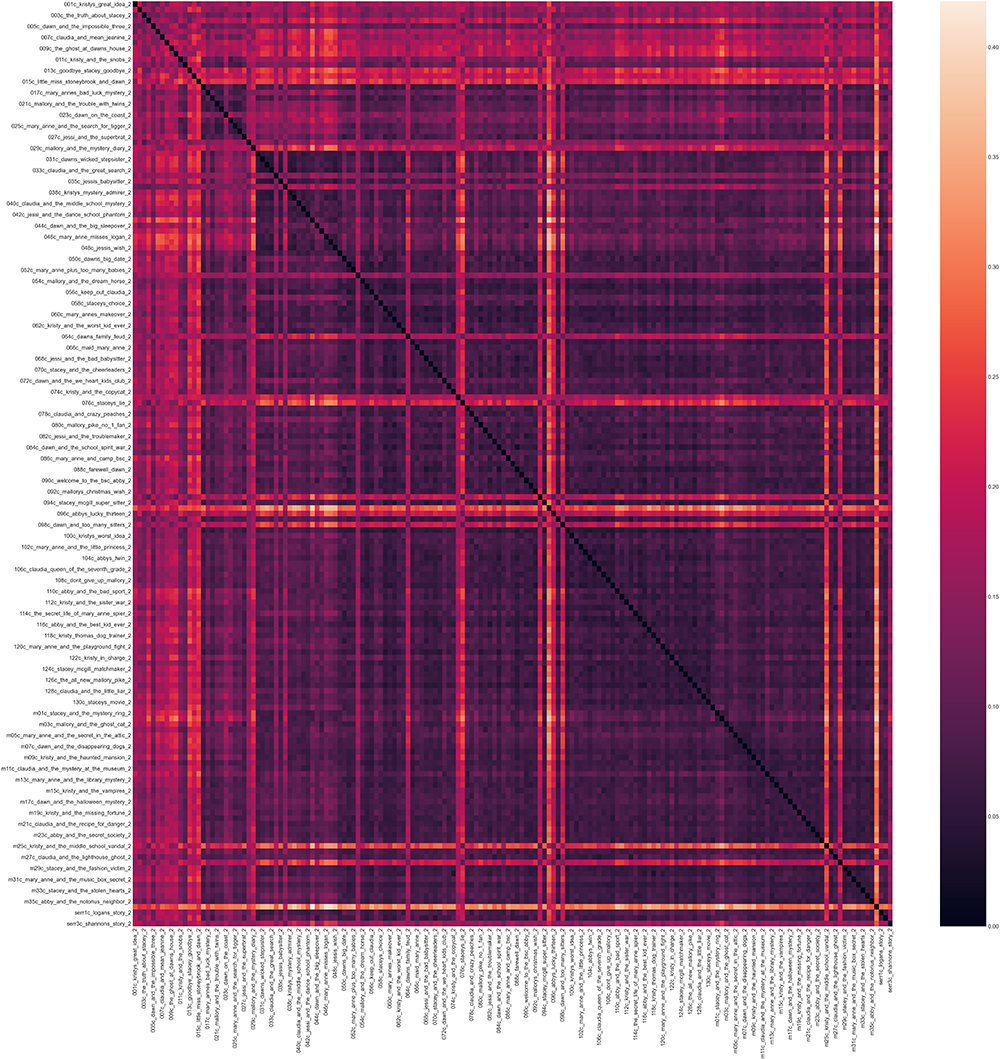

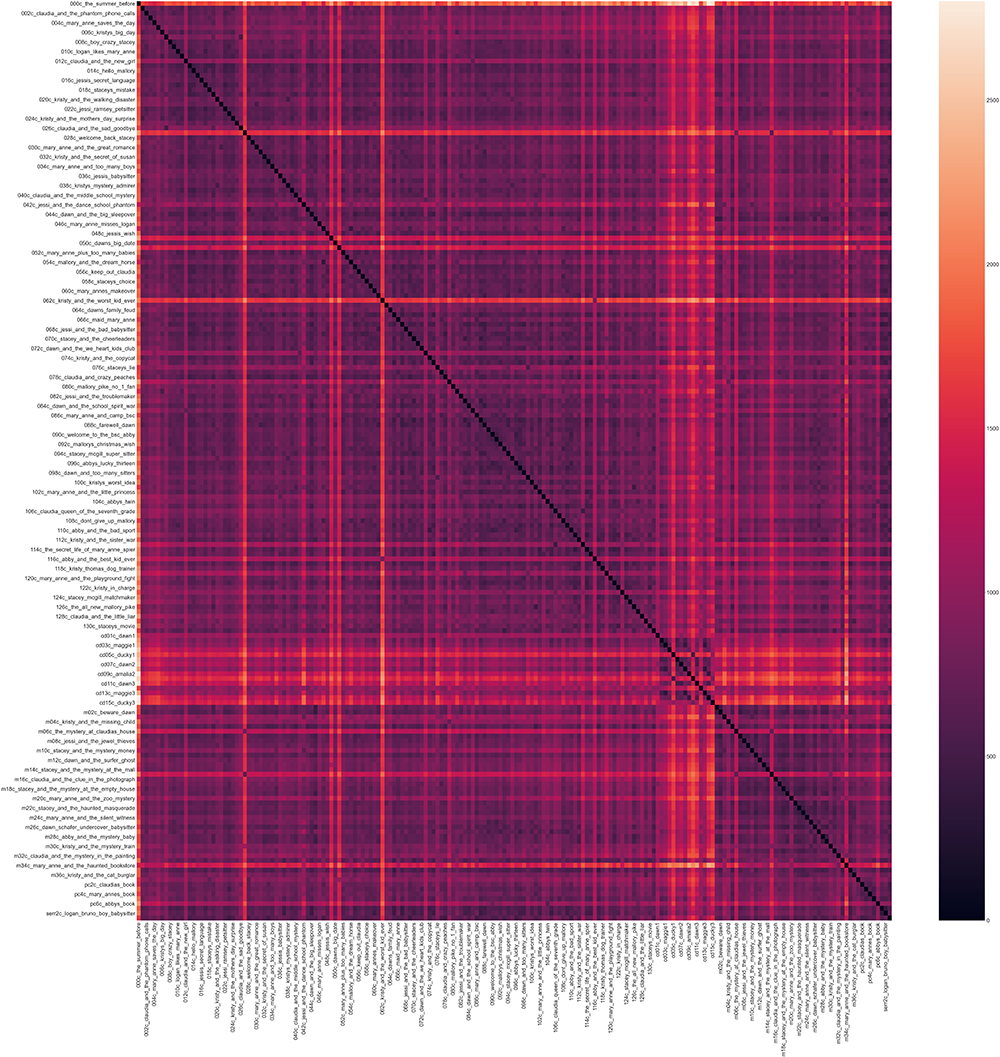

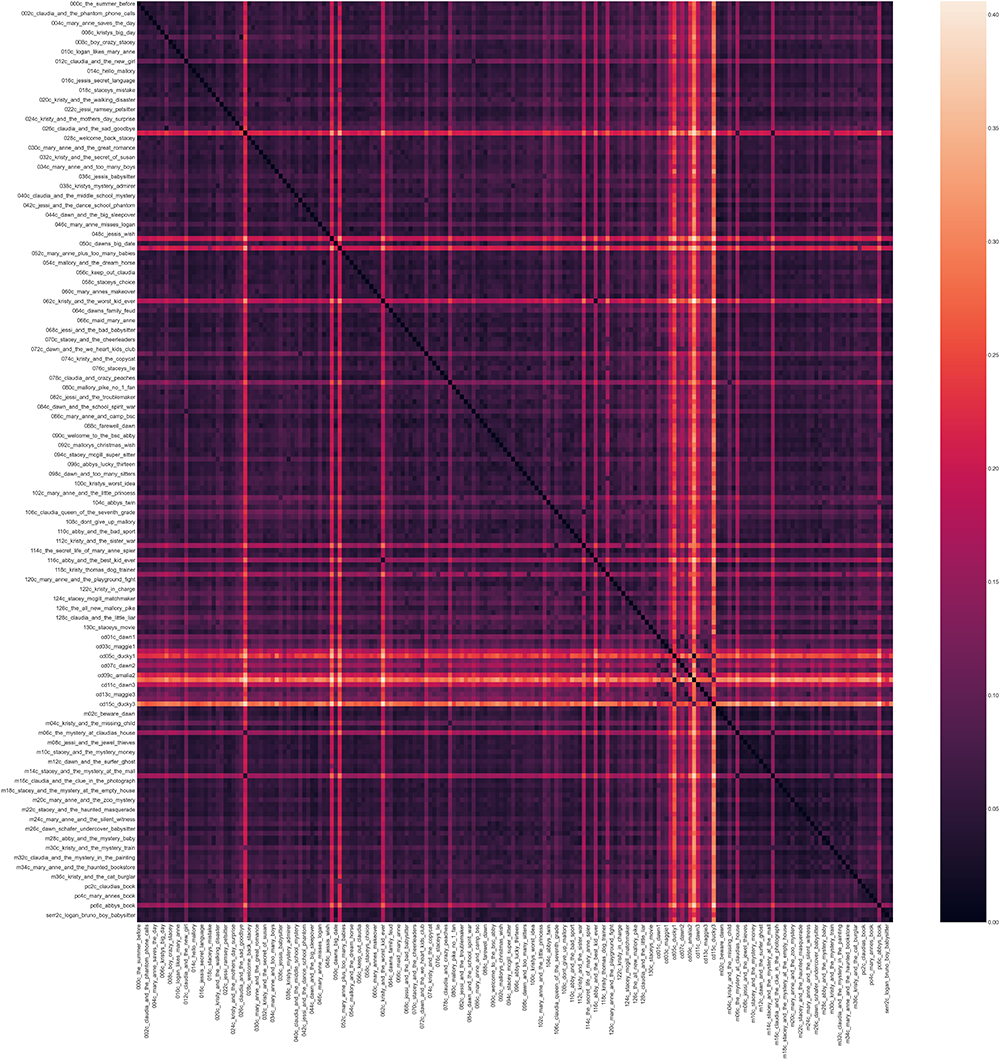

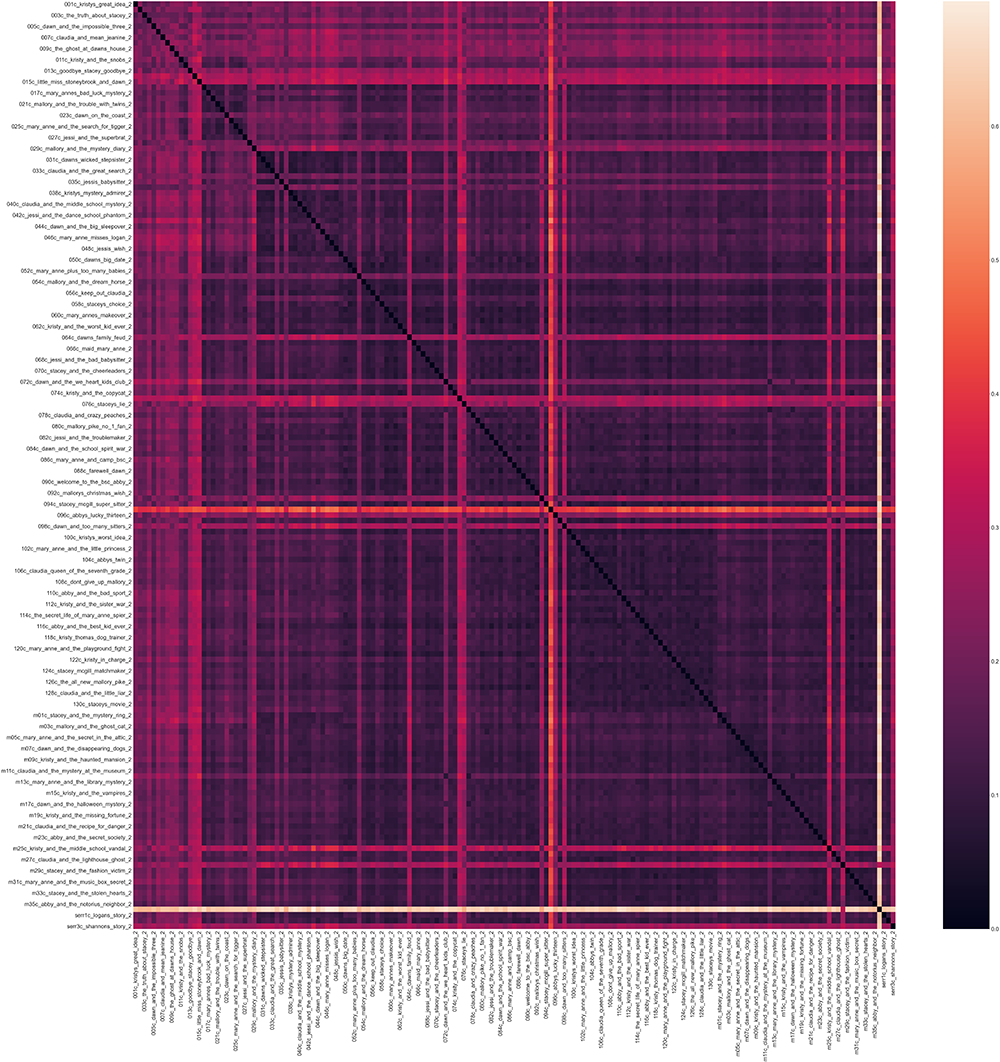

The output of the heatmap visualization I used to get a sense of the results is a little dazzling. It looks more like one of Mary Anne’s plaid dresses than something you could make sense out of. Each book (in numerical order) is along the vertical and horizontal axes, so you have a black line running diagonally showing that every book is identical to itself.

If you zoom in enough to read the labels (you can save the images from this Jupyter notebook by ctrl+clicking on them, or you can find them in the GitHub repo), you can start to pick out patterns. California Diaries: Dawn 1 is one of the bright light-colored lines, meaning it’s very different from the other books. That’s not too surprising, though it’s more surprising that it also looks different from the other California Diaries books. Abby’s Book from the Portrait Collection (that character’s “autobiography”) is very different from the other Portrait Collection books. There are also a few clusters of noticeably different books scattered throughout the corpus: Mystery #32: Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting and Mystery #34: Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore were about as distinct as California Diaries #1. BSC #103: Happy Holidays, Jessi, BSC #73: Mary Anne and Miss Priss, and BSC #62: Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever also jump out as visibly distinct. There’s also a band of higher general similarity ranging from books #83-101.

It was one of those classic DH moments where I now had a bunch of data, and no idea where to start on interpreting it. 🤯

But then I started to wonder about how good my data even was. Like I mentioned earlier, Euclidean distance is very sensitive to the length of the texts I was comparing. Was it a fair assumption that the books would all be the same length? DH methods make it easy to put our assumptions to the test.

Counting words#

To see if Euclidean distance is a good metric, we need to find out how much variation there is in the text length. For Euclidean distance to work well, we need the input text to be close to the same length.

The first way we’ll count is based on BSC sub-series. The code below depends on some DSC-specific file-naming conventions, where each file is named with an abbreviation representing the series, followed by the book number.

Counting words in full books#

We’ve already specified above that filedir is where all our full-text files are, and we should already be in that directory in order to run Euclidean distance. So we can just run this code on the files in our current directory, which should be the full-text files.

#Creates a CSV file for writing the word counts

with open('bsc_series_wordcount.csv', 'w', encoding='utf8') as out:

#Writes the header row

out.write('filename, wordcount, series')

#New line

out.write('\n')

#For each file in the directory

for filename in os.listdir(filedir):

#If it ends in .txt

if filename.endswith('.txt'):

#Open that file

file = open(filename, "rt", encoding="utf8")

#Read the file

data = file.read()

#Split words based on white space

words = data.split()

#If filename starts with 'ss' for Super Special

if filename.startswith('ss'):

#Assign 'ss' as the series

series = 'ss'

#If filename starts with 'm' for Mystery

elif filename.startswith('m'):

#Assign 'm' as the series

series = 'm'

#If filename starts with 'cd' for California Diaries

elif filename.startswith('cd'):

#Assign 'cd' as the series

series = 'cd'

#If the filename starts with 'pc' for Portrait Collection

elif filename.startswith('pc'):

#Assign 'pc' as the series

series = 'pc'

#If the filename starts with 'ff' for Friends Forever

elif filename.startswith('ff'):

#Assign 'ff' as the series

series = 'ff'

#Otherwise...

else:

#It's a main series book

series = 'main'

#Print the filename, comma, length, comma, and series (so we can see it)

print(filename + ', ' + str(len(words)) + ', ' + series)

#Write out each of those components to the file

out.write(filename)

out.write(', ')

out.write(str(len(words)))

out.write(', ')

out.write(series)

#Newline so the lines don't all run together

out.write('\n')

Counting words by chapter#

Now, enter the full path to the directory with your individual-chapter files.

chapterdir = '/Users/qad/Documents/dsc/dsc_chapters/allchapters'

#Change to the directory with the individual-chapter files.

os.chdir(chapterdir)

#Creates a CSV file for writing the word counts

with open('bsc_chapter_wordcount.csv', 'w', encoding='utf8') as out:

#Write header

out.write('filename, wordcount, chapter_number')

#Newline

out.write('\n')

#For each file in the directory

for filename in os.listdir(chapterdir):

#If it ends with .txt

if filename.endswith('.txt'):

#Open the file

file = open(filename, "rt", encoding='utf8')

#Read the file

data = file.read()

#Split words at blank spaces

words = data.split()

#If the filename ends with an underscore and number

#The number goes in the "series" column (it's actually a chapter number)

if filename.endswith('_1.txt'):

series = '1'

elif filename.endswith('_2.txt'):

series = '2'

elif filename.endswith('_3.txt'):

series = '3'

elif filename.endswith('_4.txt'):

series = '4'

elif filename.endswith('_5.txt'):

series = '5'

elif filename.endswith('_6.txt'):

series = '6'

if filename.endswith('_7.txt'):

series = '7'

elif filename.endswith('_8.txt'):

series = '8'

elif filename.endswith('_9.txt'):

series = '9'

elif filename.endswith('_10.txt'):

series = '10'

elif filename.endswith('_11.txt'):

series = '11'

elif filename.endswith('_12.txt'):

series = '12'

elif filename.endswith('_13.txt'):

series = '13'

elif filename.endswith('_14.txt'):

series = '14'

elif filename.endswith('_15.txt'):

series = '15'

#Print results so we can watch as it goes

print(filename + ', ' + str(len(words)) + ', ' + series)

#Write everything out to the CSV file

out.write(filename)

out.write(', ')

out.write(str(len(words)))

out.write(', ')

out.write(series)

out.write('\n')

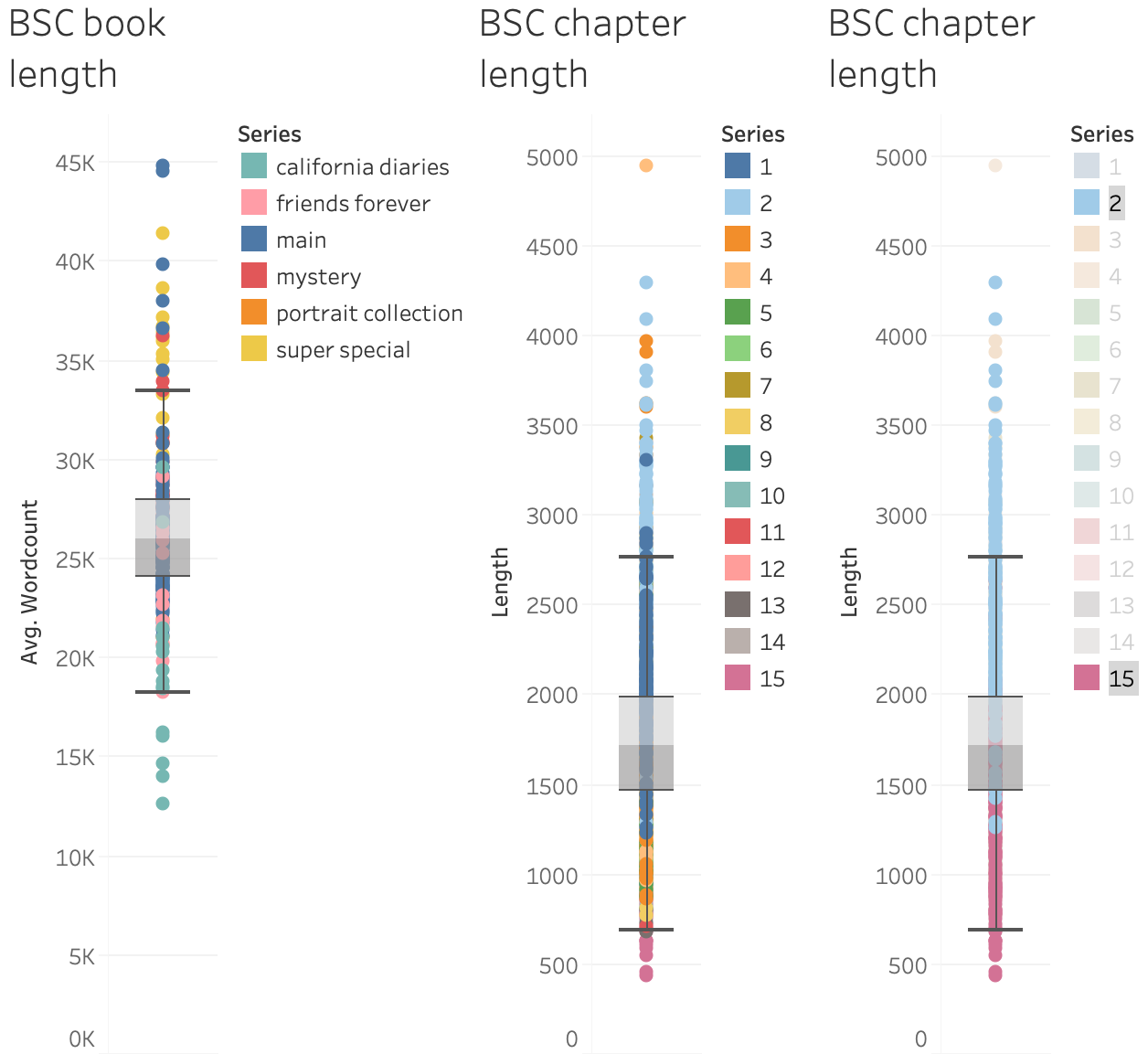

I put the output files into Tableau (Gantt visualization, configuring length as a dimension under “rows”) after running the code on the full text of all the series, and the chapter length of the main and mystery series (remember, each of those books has 15 chapters).

The books range from around 12,600 words (California Diaries: Amalia 3, which is shorter than this DSC book!), to nearly 45,000 words (Super Mystery #1: Baby-Sitters’ Haunted House). On the chapter level, there’s not a ton of variation in word length between chapters, though chapter 15 tends to be a bit shorter, and chapter 2 tends to be longer – there’s a lot of tropes to pack in!

But if we’re using Euclidean distance to compare even chapter 2s, BSC #75: Jessi’s Horrible Prank is 1,266 words and BSC #99: Stacey’s Broken Heart is 4,293 words. That alone is going to lead to a big difference in the word-count values.

When I first started playing with these text-comparison metrics (before taking the care to properly clean the data and ensure there weren’t problems with my chapter-separating code), I first tried Euclidean distance, and was fascinated by the apparent similarity of chapter 2 in the first Baby-Sitters Club book and a chapter in a California Diaries book. “What,” I wondered, “does wholesome Kristy’s Great Idea have to do with salacious California Diaries?”

I laughed out loud when I opened the text files containing the text of those chapters, and immediately saw the answer: what they had in common was data cleaning problems that led to their truncation after a sentence or two. As a Choose Your Own Adventure book might put it, “You realize that your ‘findings’ are nothing more than your own mistakes in preparing your data set. You sigh wearily. The end.” Hopefully you, like childhood me, left a bookmark that last decision point you were unsure of, and you can go back and make a different choice. But even if you have to start over from the beginning, you can almost try again when doing DH.

Cosine similarity#

Cosine similarity offers a workaround for the text-scale problems we encountered with Euclidean distance. Instead of trying to measure the distance between two points (which can be thrown off due to issues of magnitude, when one point represents a text that’s much longer than the other), it measures the cosine of the angle between them and calls it similarity. You may have also filed “cosine” away under “high school math I hoped to never see again”, but don’t panic! As trigonometry starts to flood back at you, you might find yourself wondering, “Why cosine similarity, and not any of its little friends, like sine or tangent?” After all, wouldn’t it be fun to burst into the chorus of Ace of Base’s “I Saw the Sine” whenever you worked out the text similarity?